Thomas Eakins

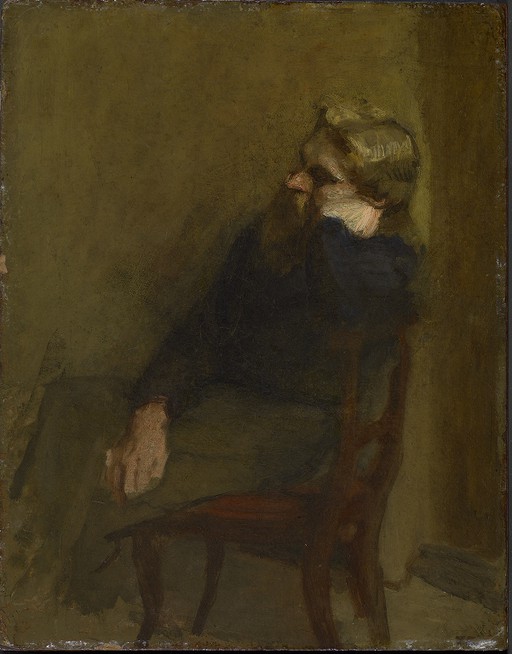

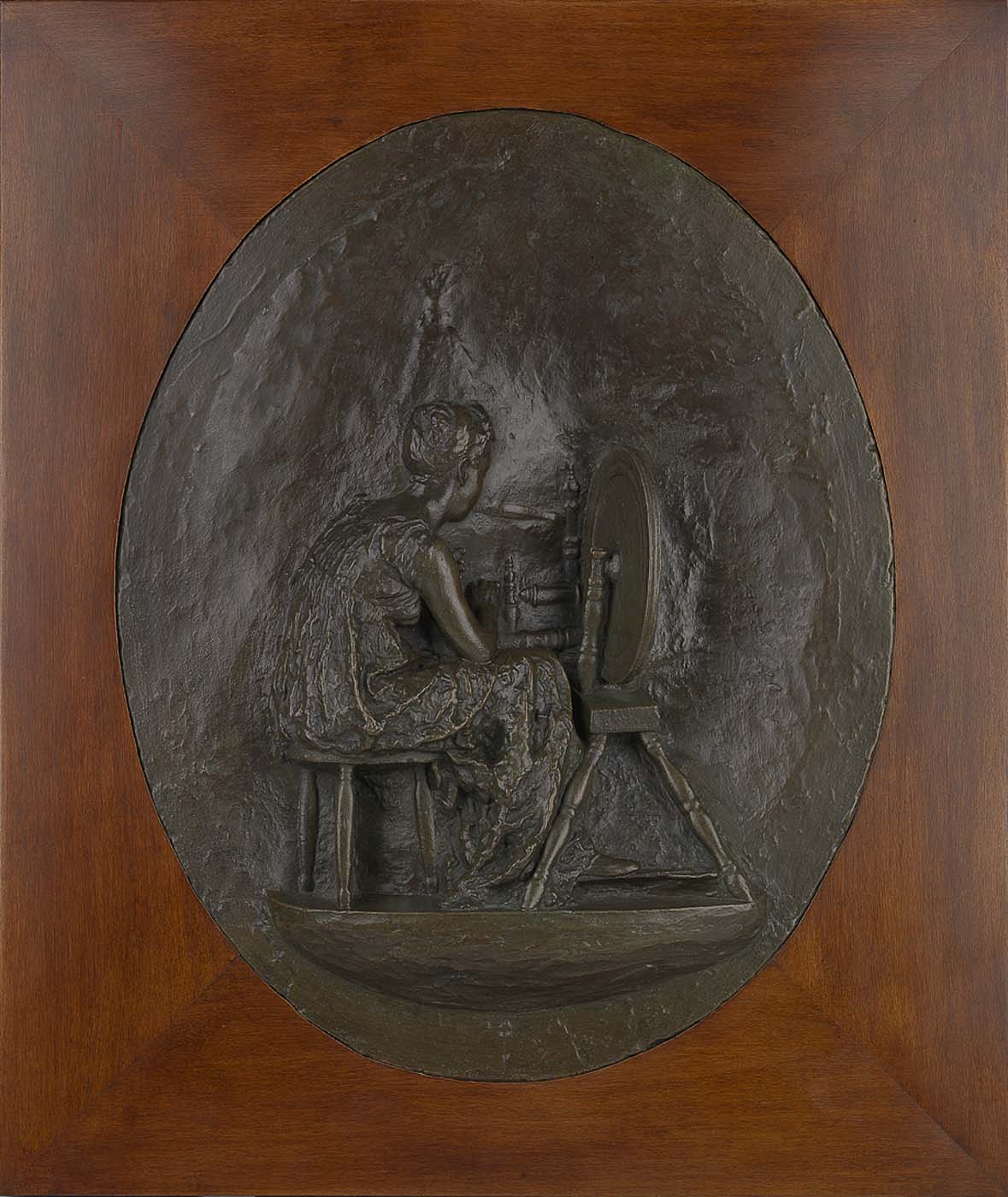

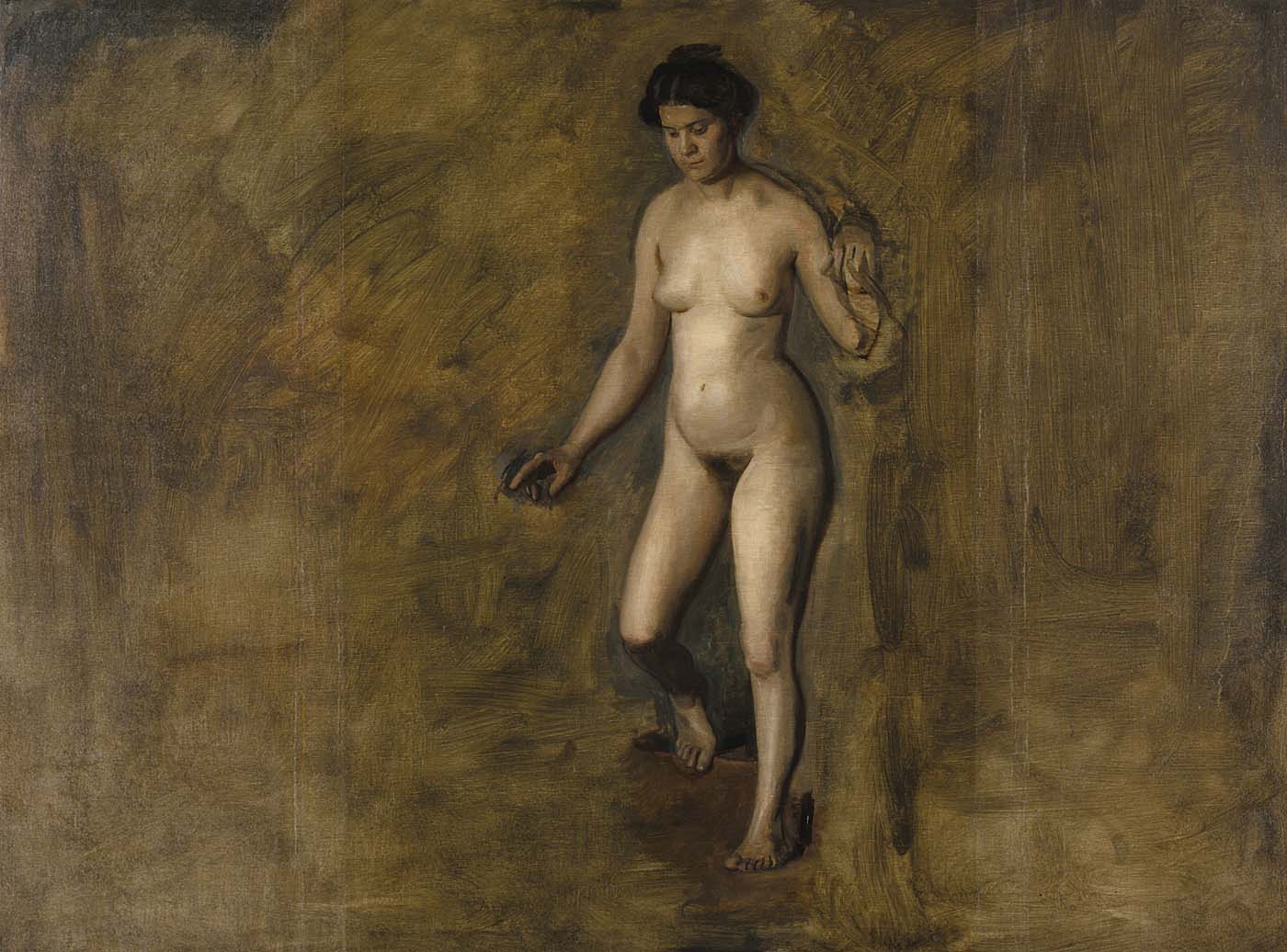

Thomas Eakins shared his era's fascination with the individual human being—with his or her capacity for intellectual achievement, psychological intricacy, and vulnerability to the ravages of nature. Yet among painters of his time Eakins was unusual in that he expressed this interest directly. Other artists turned their attention to nature, as did the Impressionists and other late-nineteenth-century landscapists, spending a lifetime painting fields, mountains, and flowers in dazzling sunlight. Some artists found satisfaction in still life arrangements—small worlds man had created—and still others painted genre scenes in which men and women pursued casual activity. Eakins was notable in that he alone seemed to understand the implications for art of the late-nineteenth-century intellectual attention to the nature of man. He might have said what the English lexicographer and critic Samuel Johnson made clear a century earlier: "A blade of grass is always a blade of grass. Men and women are my subjects of inquiry."

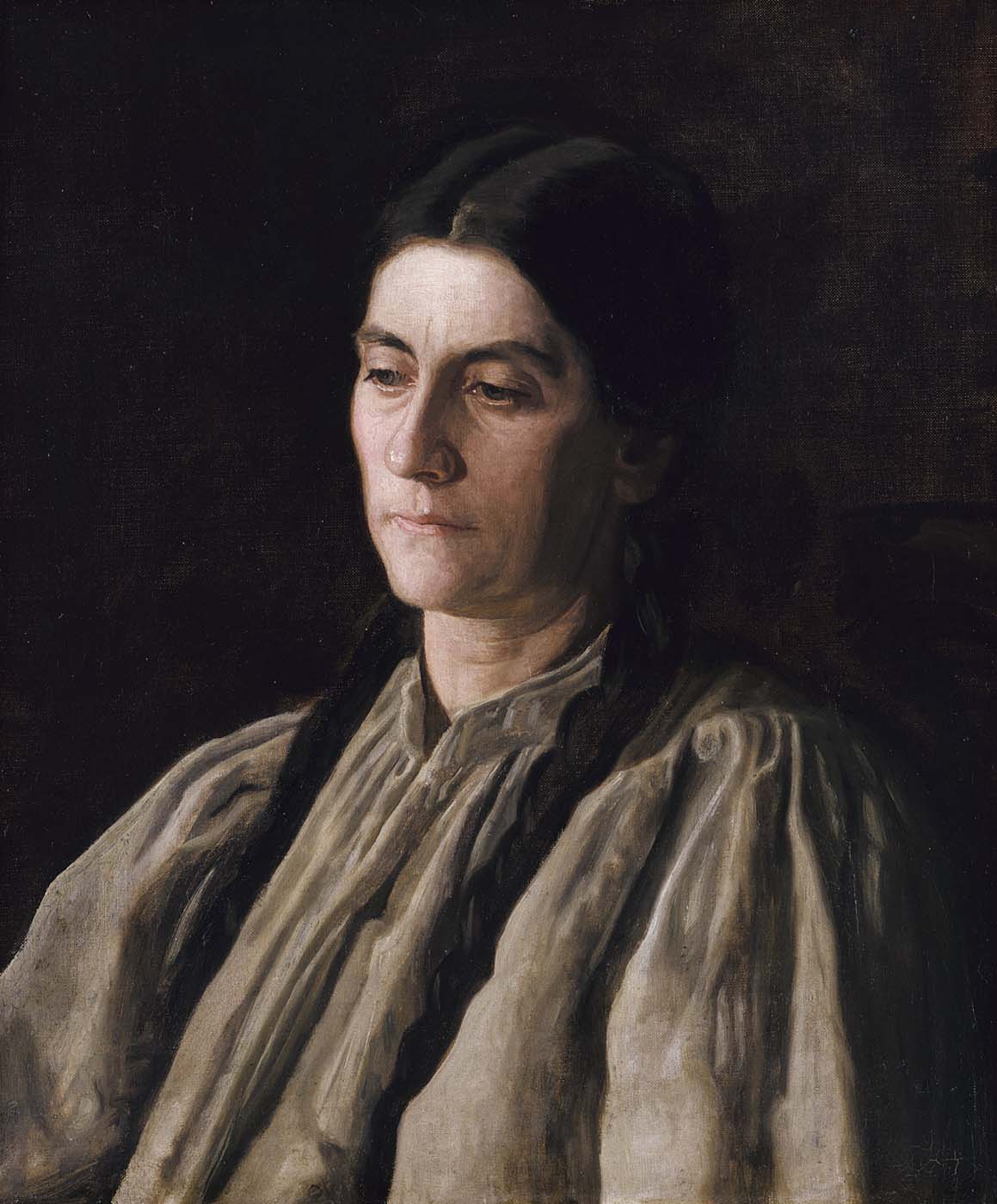

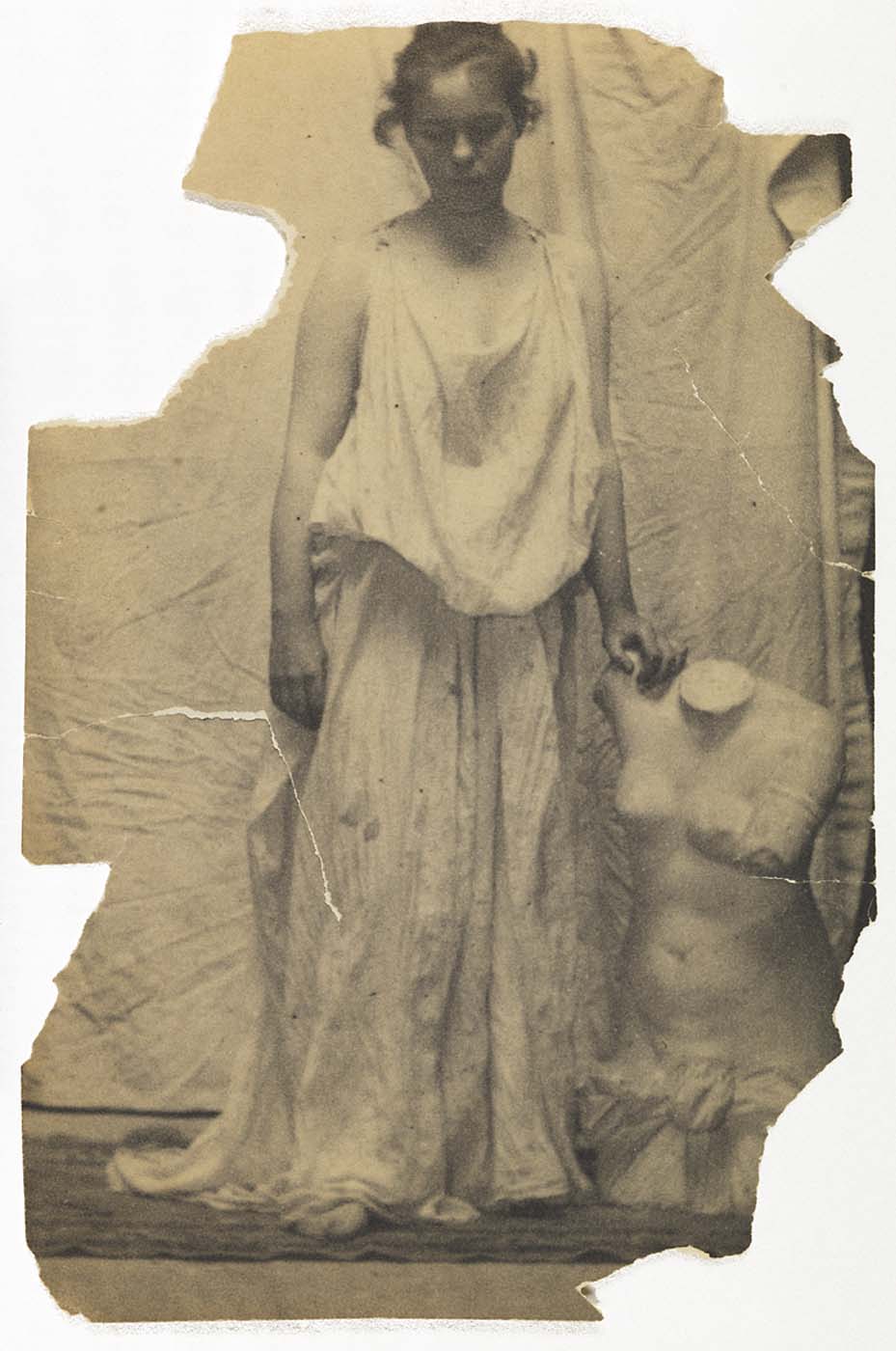

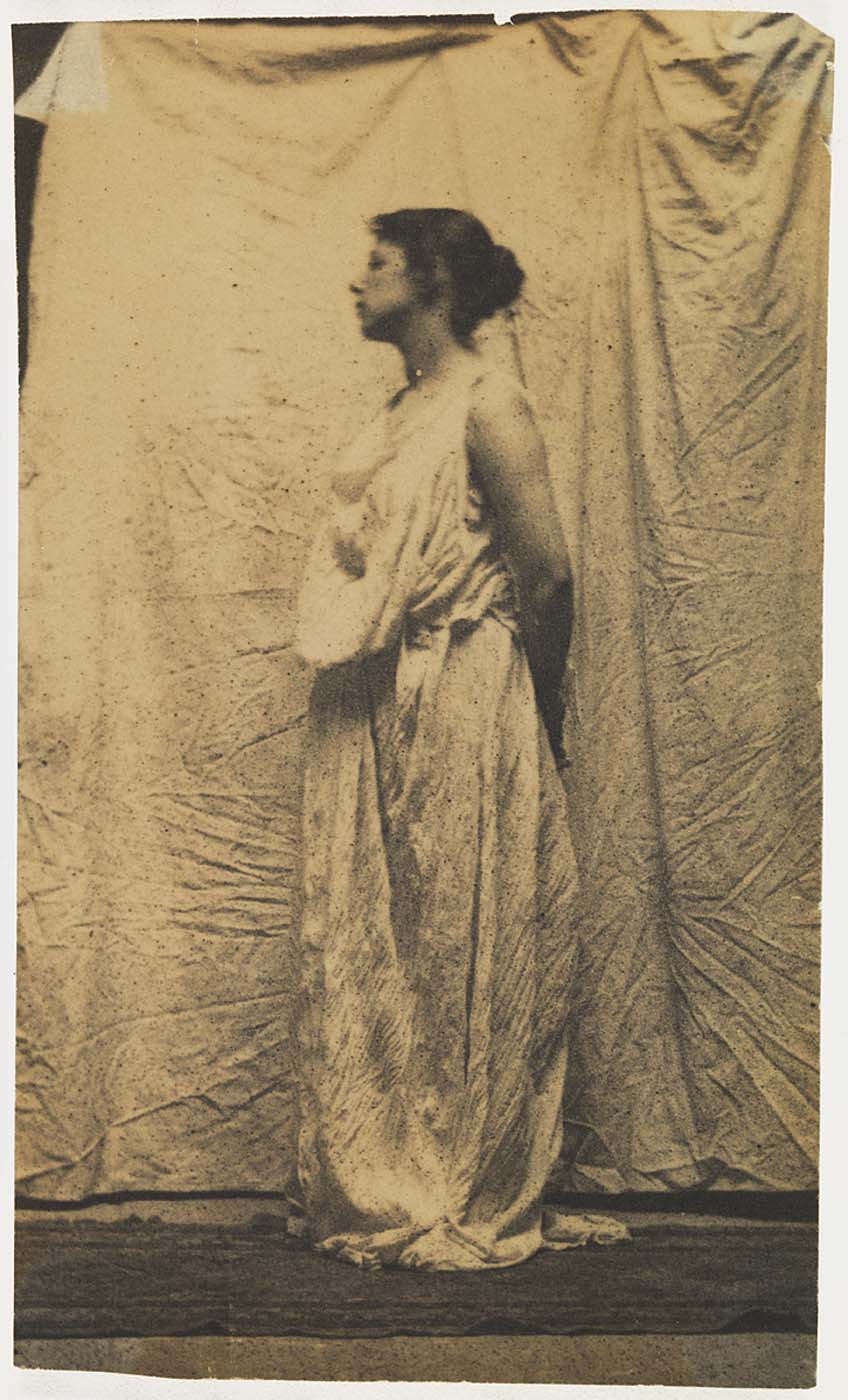

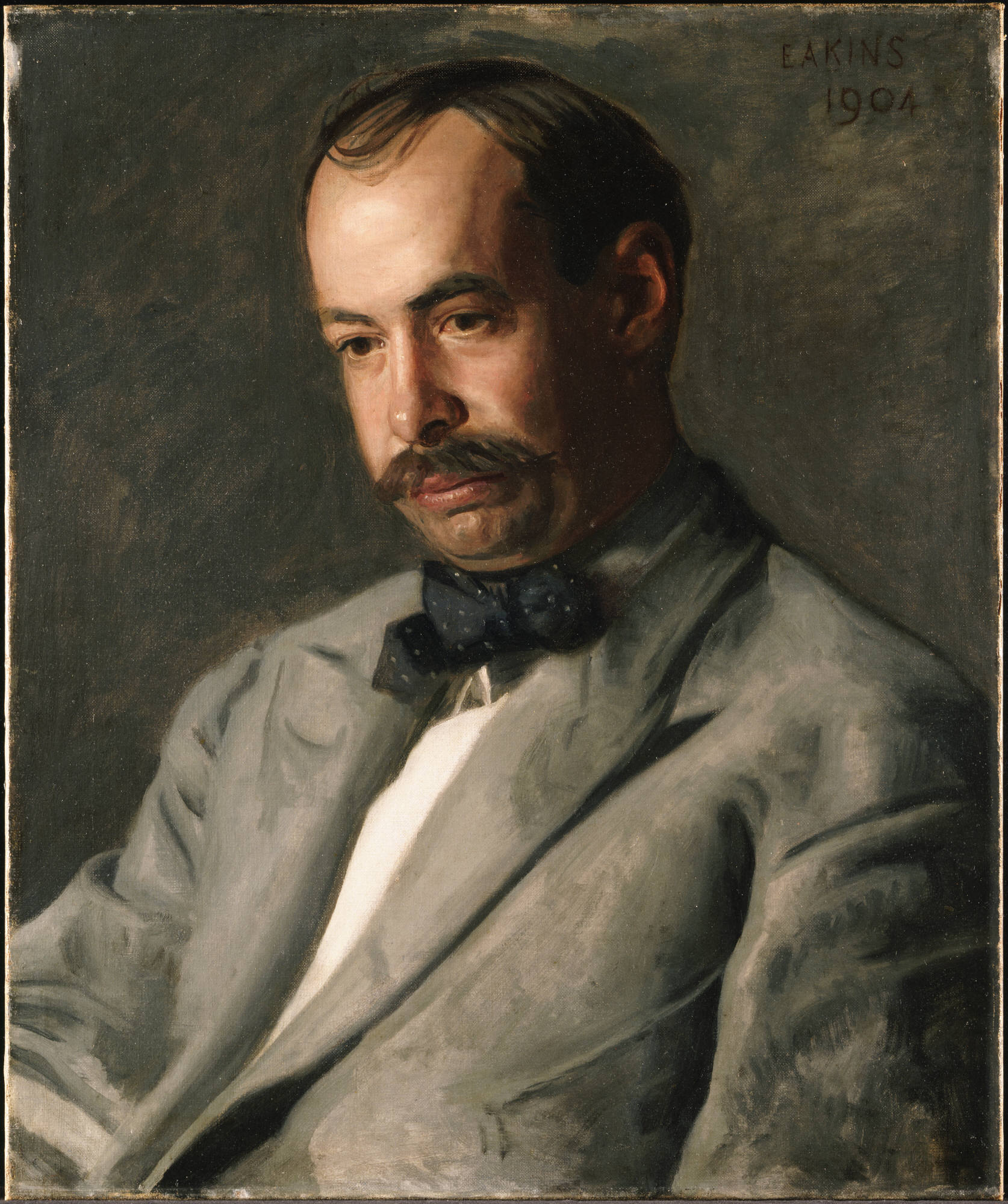

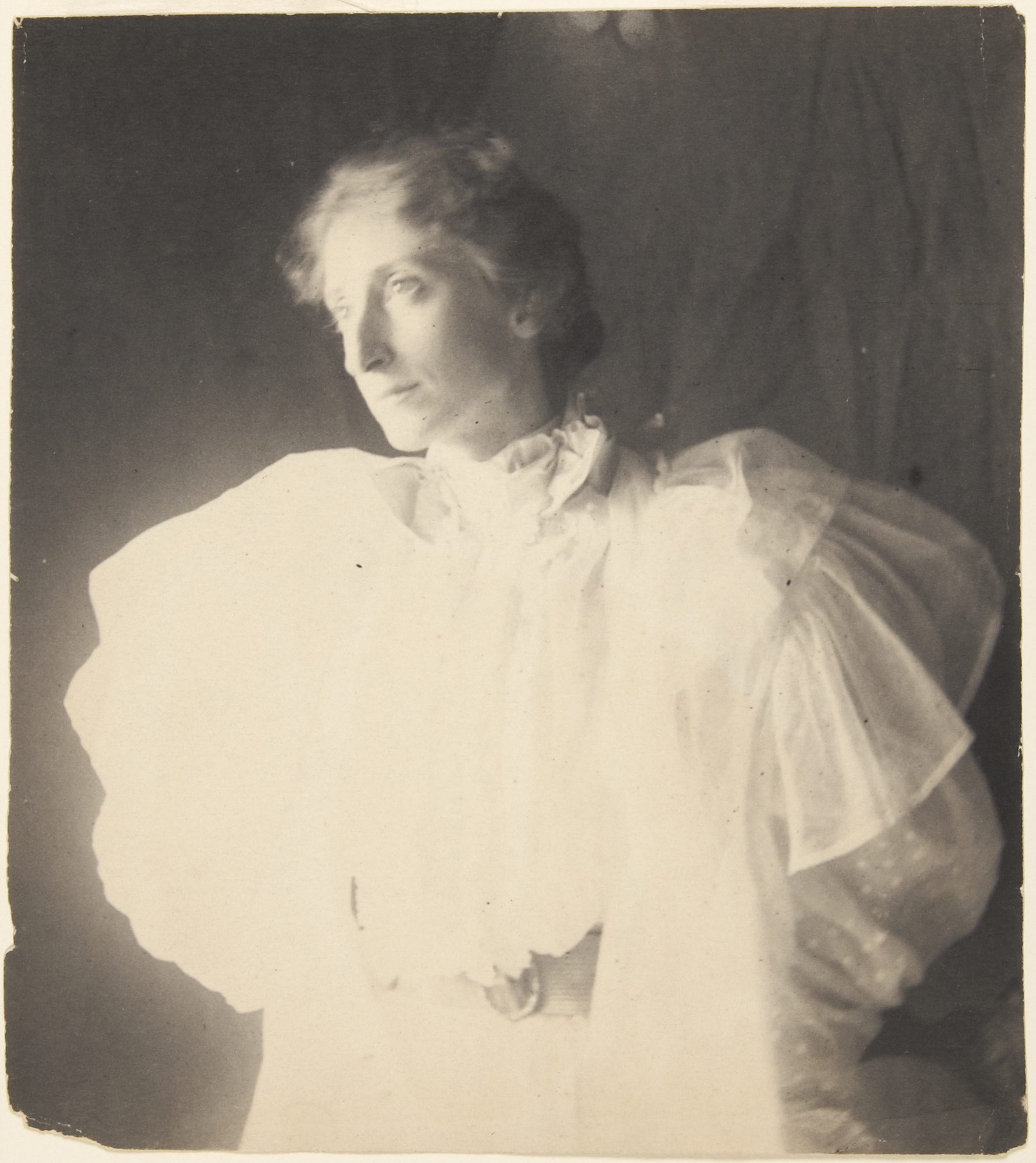

To carry out his study of men and women, Eakins chose the portrait format. Traditionally portraits had been commissioned, the artist collaborating with the sitter to portray him or her as the sitter wished to be viewed. But Eakins chose his subjects and uncompromisingly portrayed them as he saw them. When occasionally he did paint a commissioned work, the artist's assumption that he was the seer usually caused his patron to have second thoughts about living with the result.

Eakins's respect for human achievement led him to ask a number of scientists, physicians, writers, athletes, and musicians to sit for him. Most of these people lived and worked in Philadelphia, where Eakins spent his entire life except for the period from 1866 to 1870 when he studied in France and Spain.

Early in his career he typically painted large works that featured his subjects in their professional environment—for example, a surgical clinic, a boxing ring, or a concert stage. Eakins's extraordinary sensitivity to each human being's interior nature—even in works that portrayed subjects in their public capacities—their gaze or gesture with a private quietness that the artist had noticed. Later in his career, he eliminated aspects of the environment in favor of the simple bust portrait focusing on this introspective quality.

National Museum of American Art (CD-ROM) (New York and Washington D.C.: MacMillan Digital in cooperation with the National Museum of American Art, 1996)

Objects at Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields (1)

Objects at Gilcrease Museum (1)

Objects at Dallas Museum of Art (2)

Objects at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art (3)

Objects at Colby College Museum of Art (4)

Objects at Smithsonian American Art Museum (6)

Objects at Princeton University Art Museum (9)

Objects at Archives of American Art (13)