Henry Ossawa Tanner

"My effort has been to not only put the Biblical incident in the original setting … but at the same time give the human touch 'which makes the whole world kin' and which ever remains the same." —Lynda Roscoe Hartigan, Sharing Traditions: Five Black Artists in Nineteenth-Century America (Washington D.C., published for National Museum of American Art by the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985), 106.

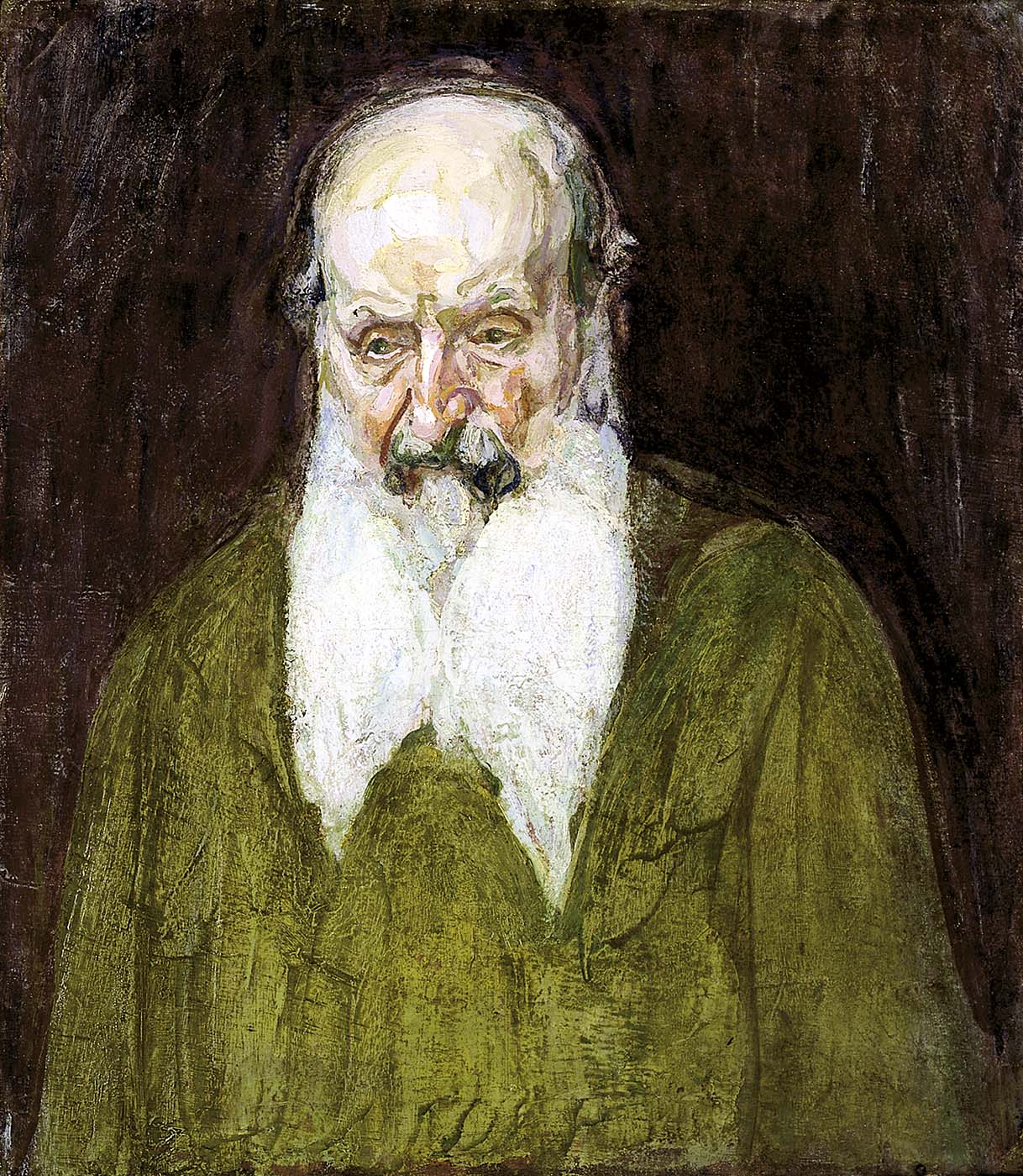

The most distinguished African-American artist of the nineteenth century, Henry Ossawa Tanner was also the first artist of his race to achieve international acclaim. Tanner was born on June 21, 1859, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Benjamin Tucker and Sarah Miller Tanner. Tanner's father was a college-educated teacher and minister who later became a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopalian Church. Sarah Tanner was a former slave whose mother had sent her north to Pittsburgh through the Underground Railroad. Tanner's family moved frequently during his early years when his father was assigned to various churches and schools. In 1864 Tanner's family settled in Philadelphia where his early artistic interests were developed. At age thirteen, Tanner decided to become an artist when he saw a painter at work during a walk in Fairmount Park near his home. Throughout his teens, Tanner painted and drew constantly in his spare time and tried to look at art as much as possible in Philadelphia art galleries. He also studied briefly with two of the city's minor painters.

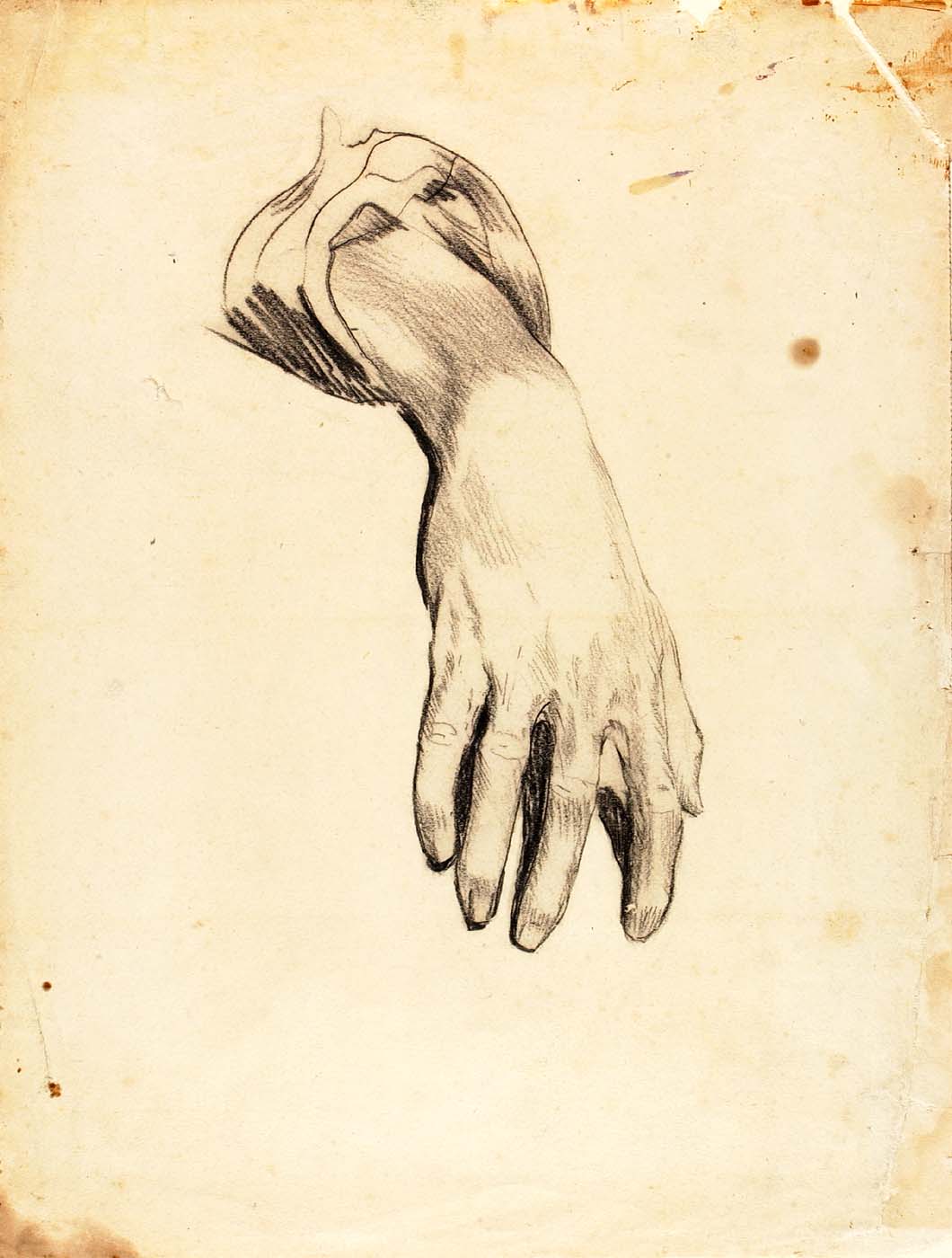

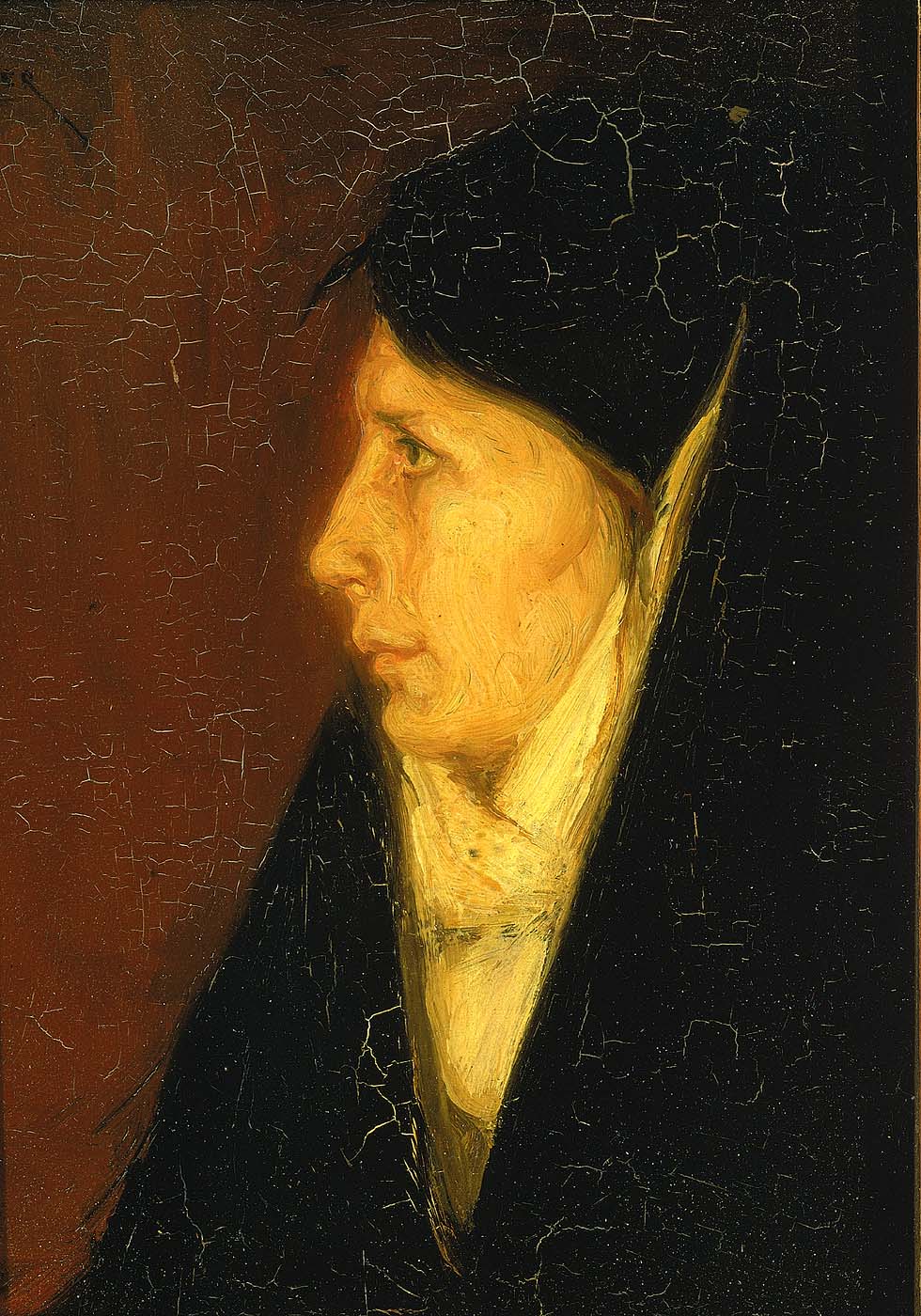

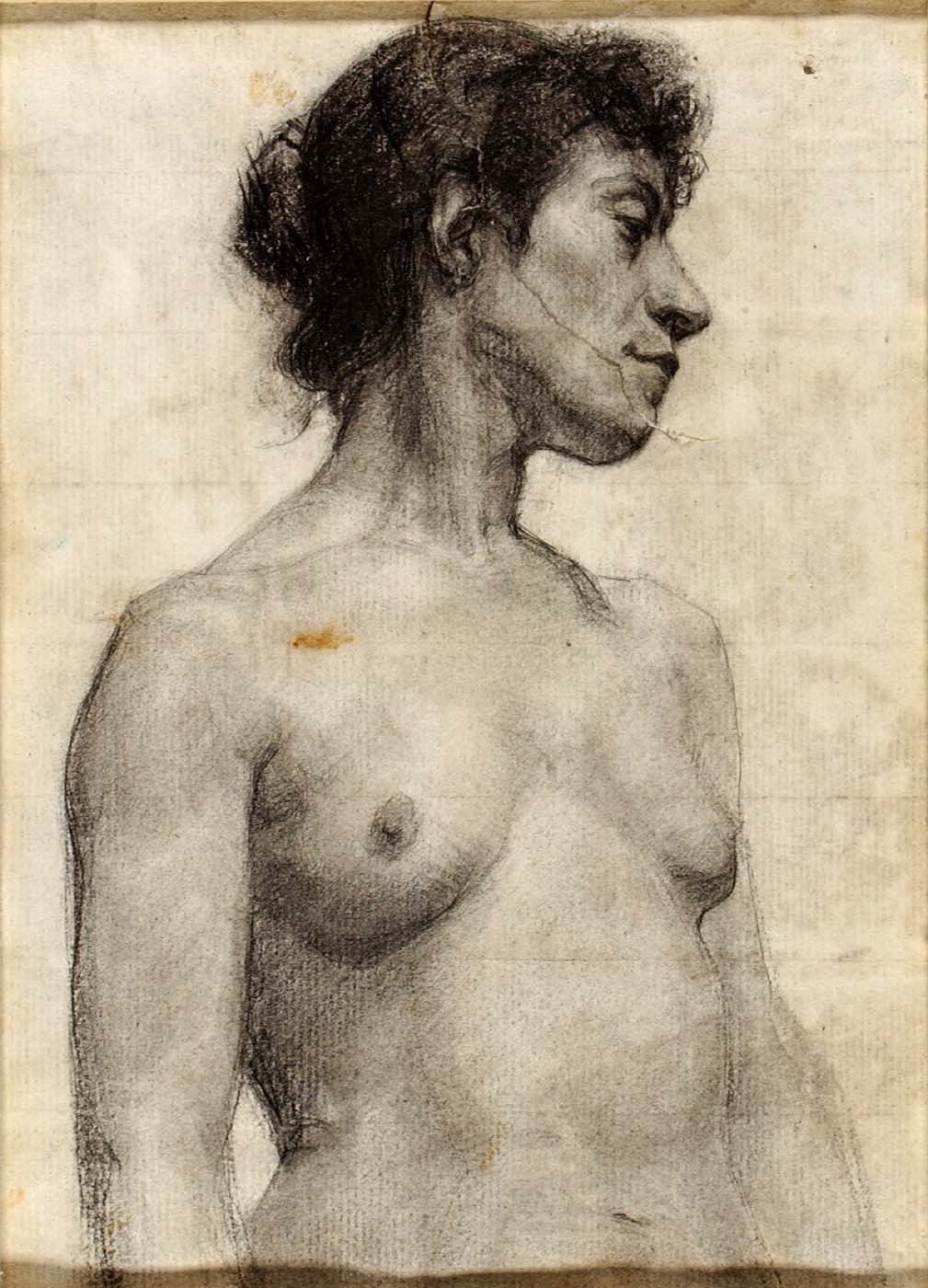

Eager to discourage his son's interest in art, Bishop Tanner apprenticed him to a friend to learn the milling business. For Tanner, a frail young man whose health was never strong throughout his life, the work in the flour mill proved too strenuous and he became seriously ill. His parents encouraged his painting during his recuperation, and Tanner lived at home during the next few years except for several trips to the Adirondack Mountains and Florida for his health. In 1880, when Tanner was twenty-one, he enrolled in the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. There he studied with a group of master professors including Thomas Eakins. It was Eakins who exerted the greatest influence on Tanner's early style. Tanner left the Pennsylvania Academy prior to graduating to pursue the idea of combining business with art. In 1888 he moved to Atlanta, Georgia, and established a modest photography gallery where he attempted to earn a semiartistic living by selling drawings, making photographs, and teaching art classes at Clark College. In spite of his combined efforts, Tanner's Atlanta venture barely profited enough to provide living expenses.

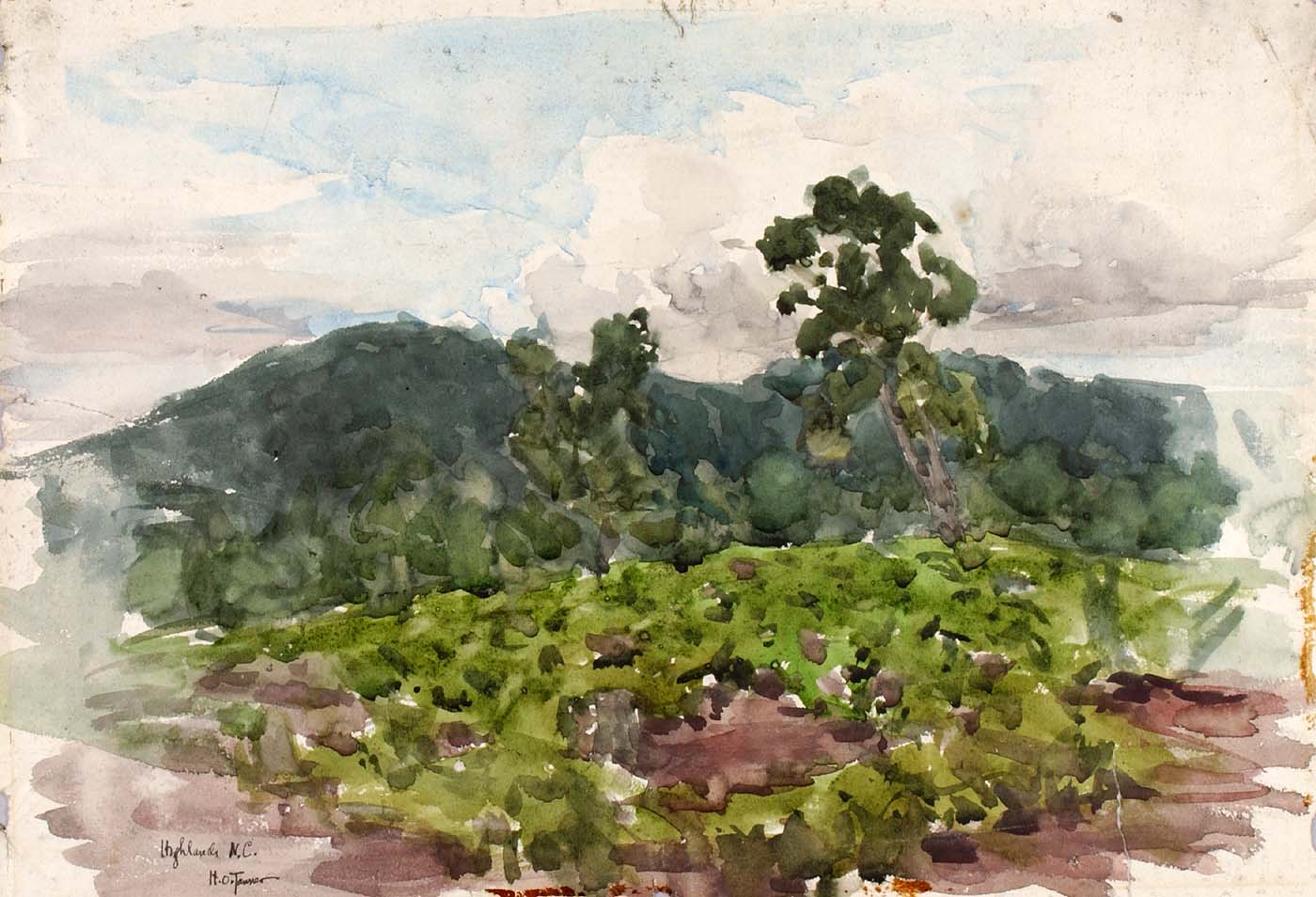

In Atlanta, Tanner met Bishop and Mrs. Joseph Crane Hartzell, who became his primary white patrons over the next several years. In the summer of 1888 Tanner sold his small gallery and moved to Highlands, North Carolina, in the Blue Ridge Mountains where he hoped to study and earn a living by his photography. He also felt that the mountains would be good for his delicate health. While there, Tanner may have made many sketches and photographs of the region and its African-American residents, some of which were later used as subjects in his most important early paintings.

In the fall of 1888, Tanner returned to Atlanta and taught drawing for two years at Clark College. After discussing his ambitions to travel abroad with Bishop and Mrs. Hartzell, they arranged an exhibition of Tanner's works in Cincinnati in the fall of 1890. When no paintings were sold, the Hartzells bought the entire collection. This endowment allowed Tanner to sail for Rome in January 1891. After brief stays in Liverpool and London, Tanner arrived in Paris. He was so impressed by this center of art and artists that he abandoned his plans to study in Rome.

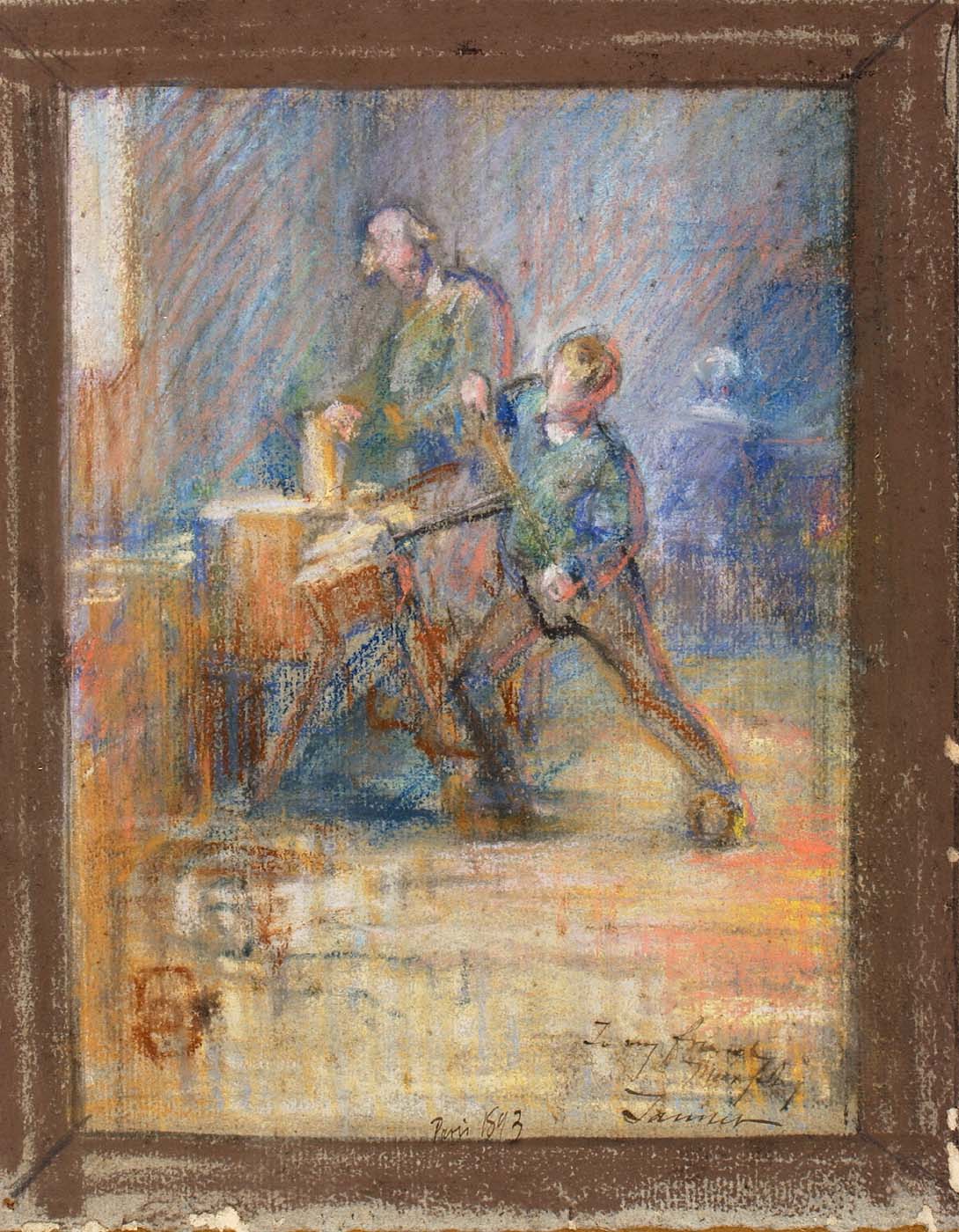

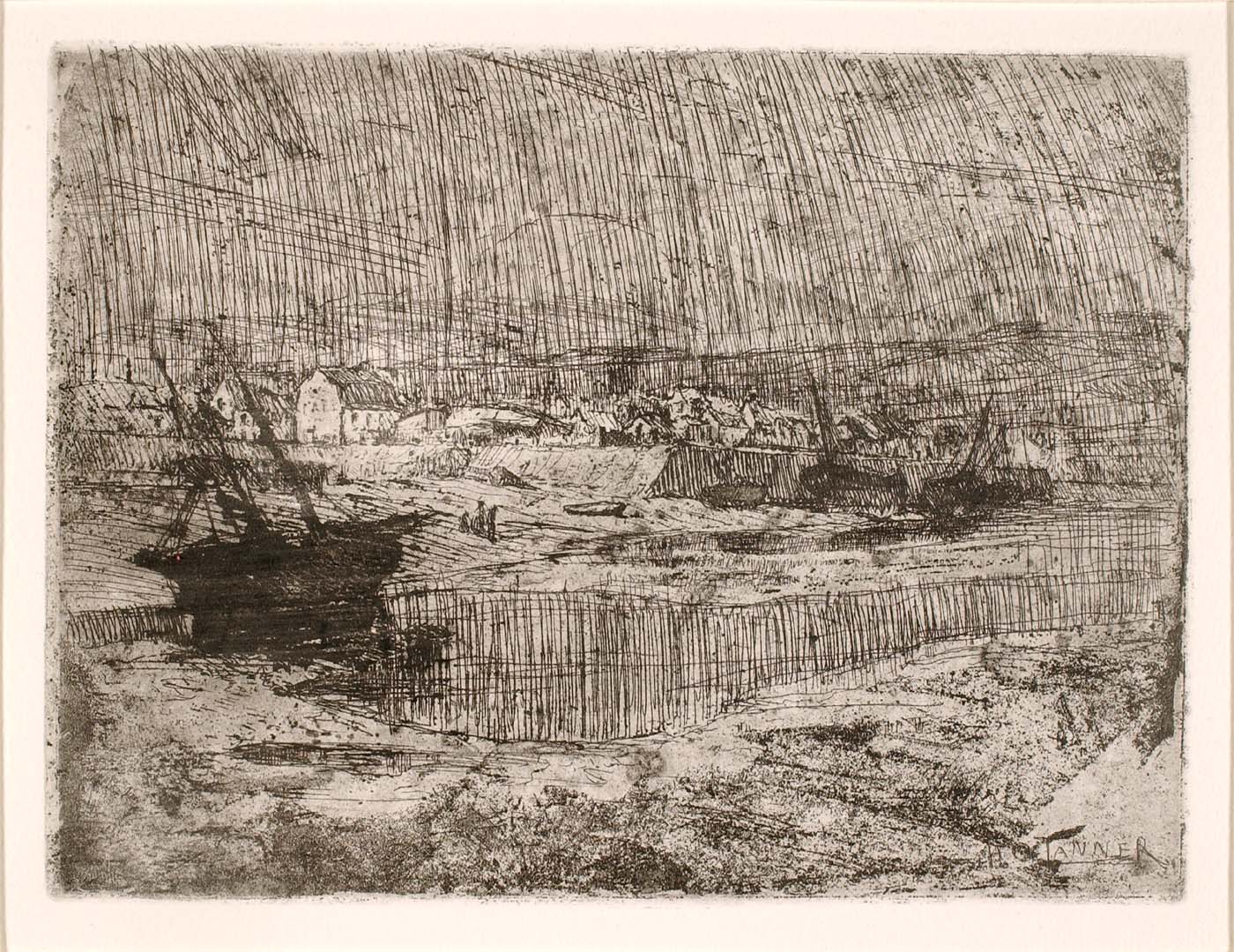

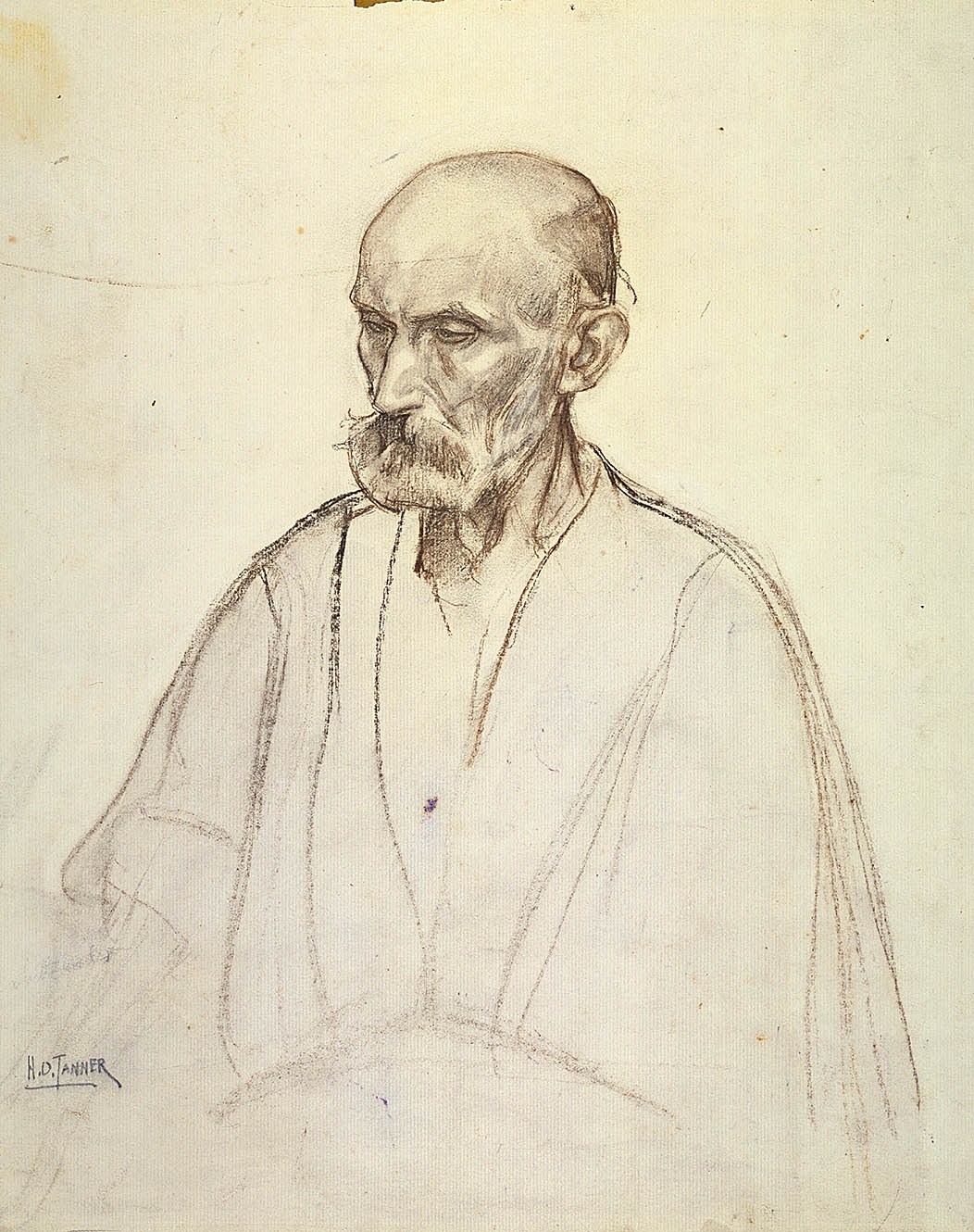

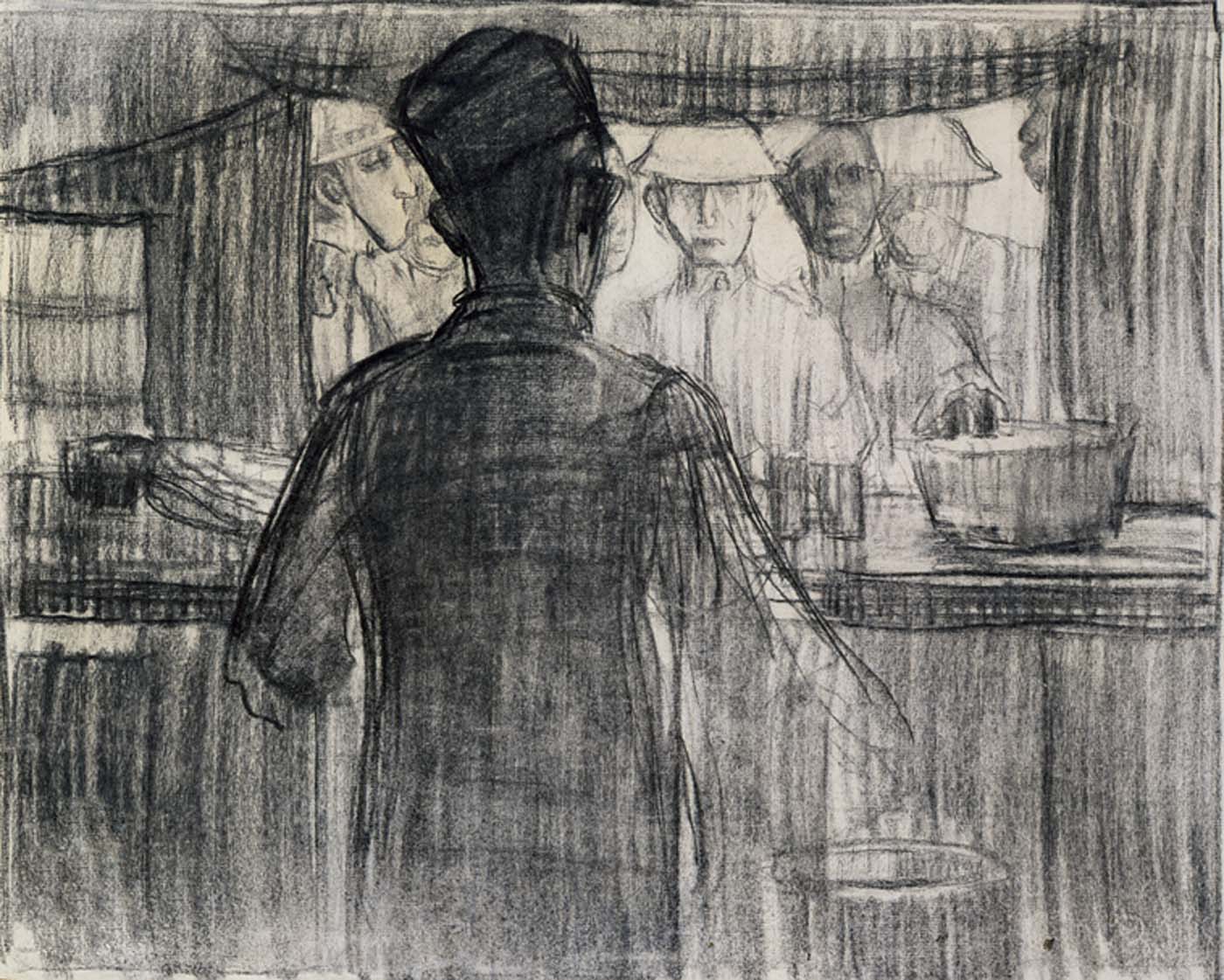

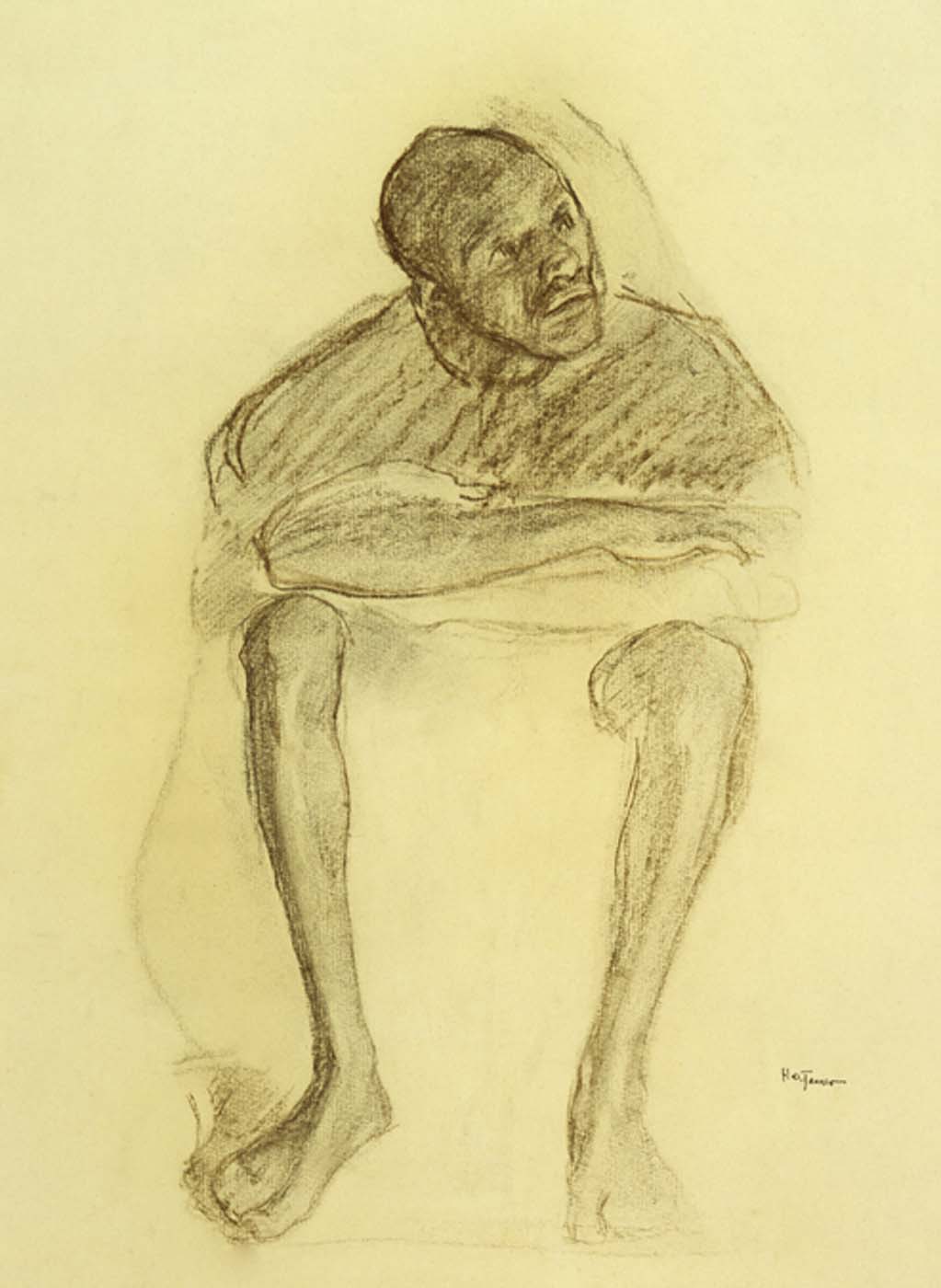

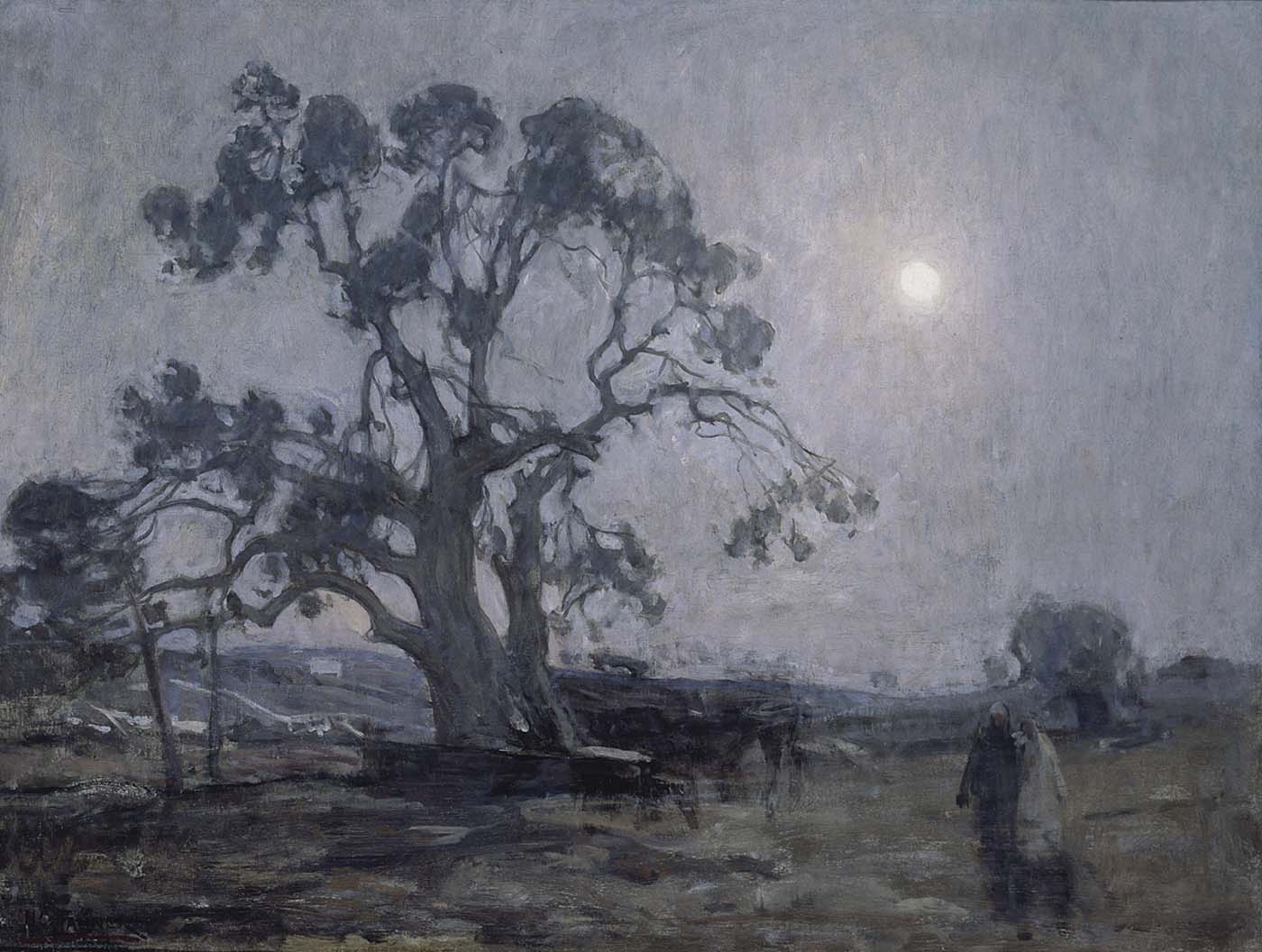

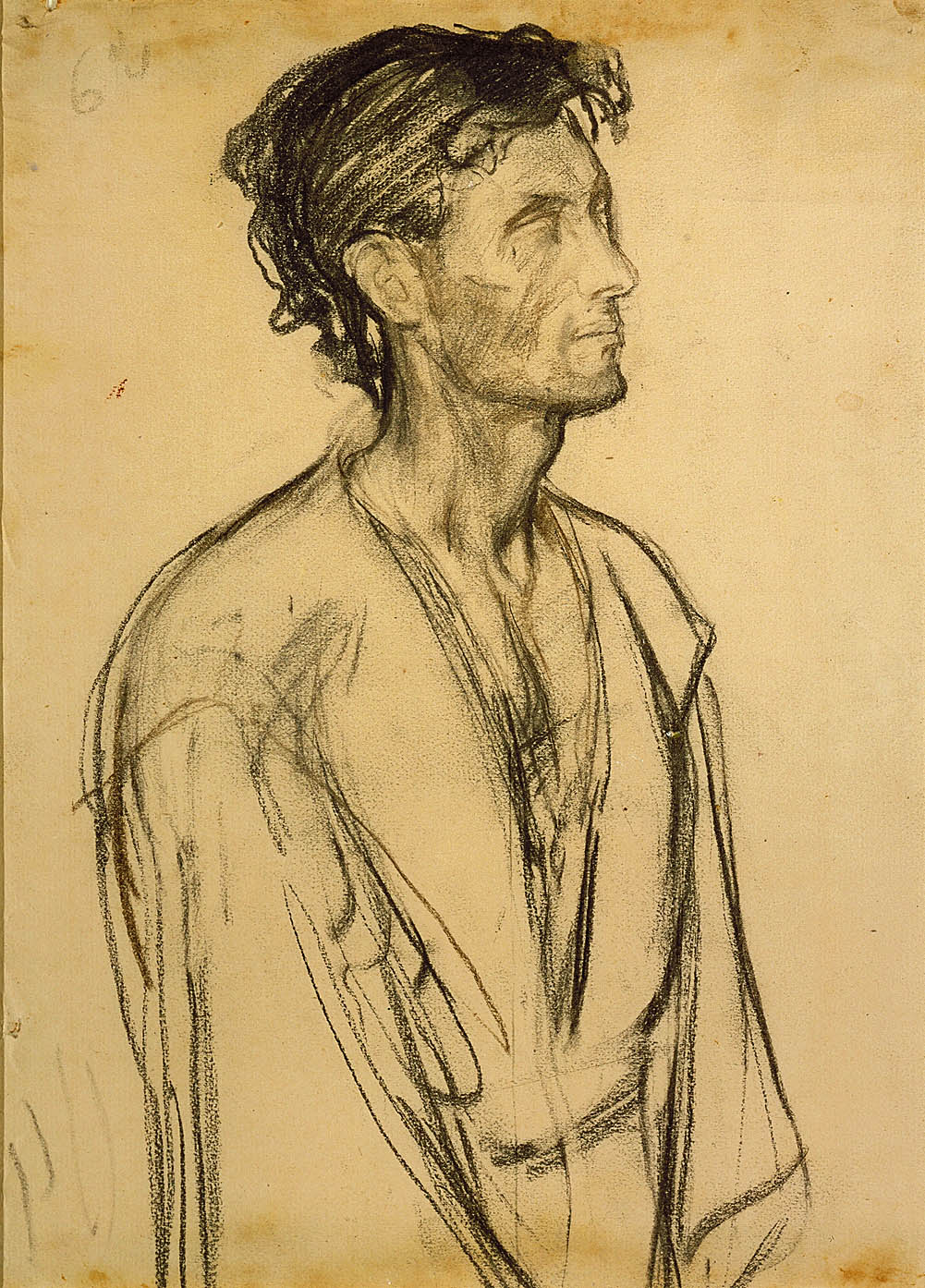

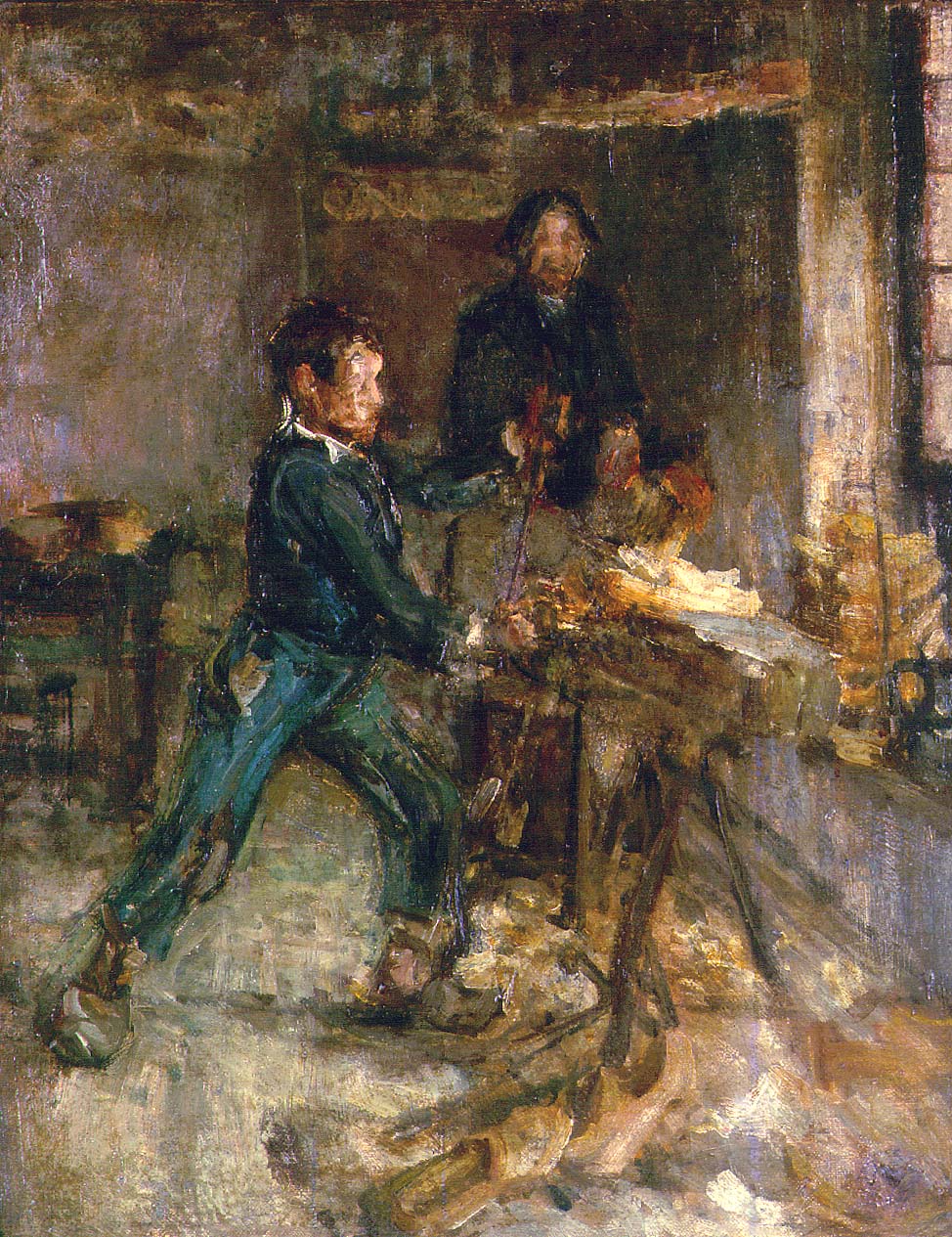

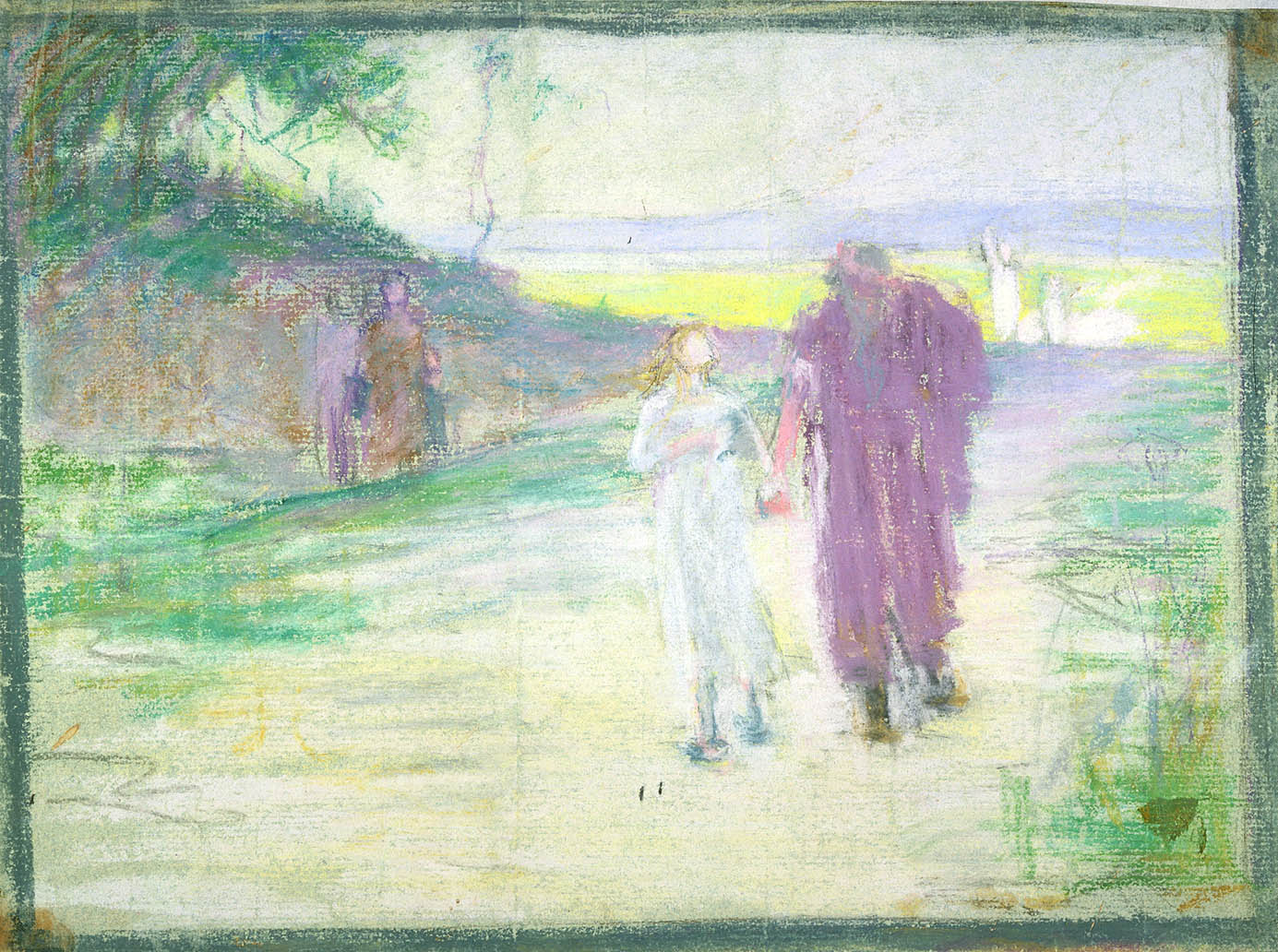

In Paris, Tanner enrolled in the Académie Julian where the painters Jean Paul Laurens and Jean Joseph Benjamin-Constant were among his teachers. It was not long before he painted two of his most important works depicting African-American subjects, The Banjo Lesson of 1893 and The Thankful Poor of 1894. During the summers of 1892 and 1893, Tanner left Paris and lived in isolated rural areas in Brittany. His best-known paintings from that period are The Bagpipe Lesson of 1894 and The Young Sabot Maker of 1895. Both depict French peasants, and Tanner assimilated the inhabitants of his rural French environment into his works as he had done previously in the mountains of Highlands, North Carolina.

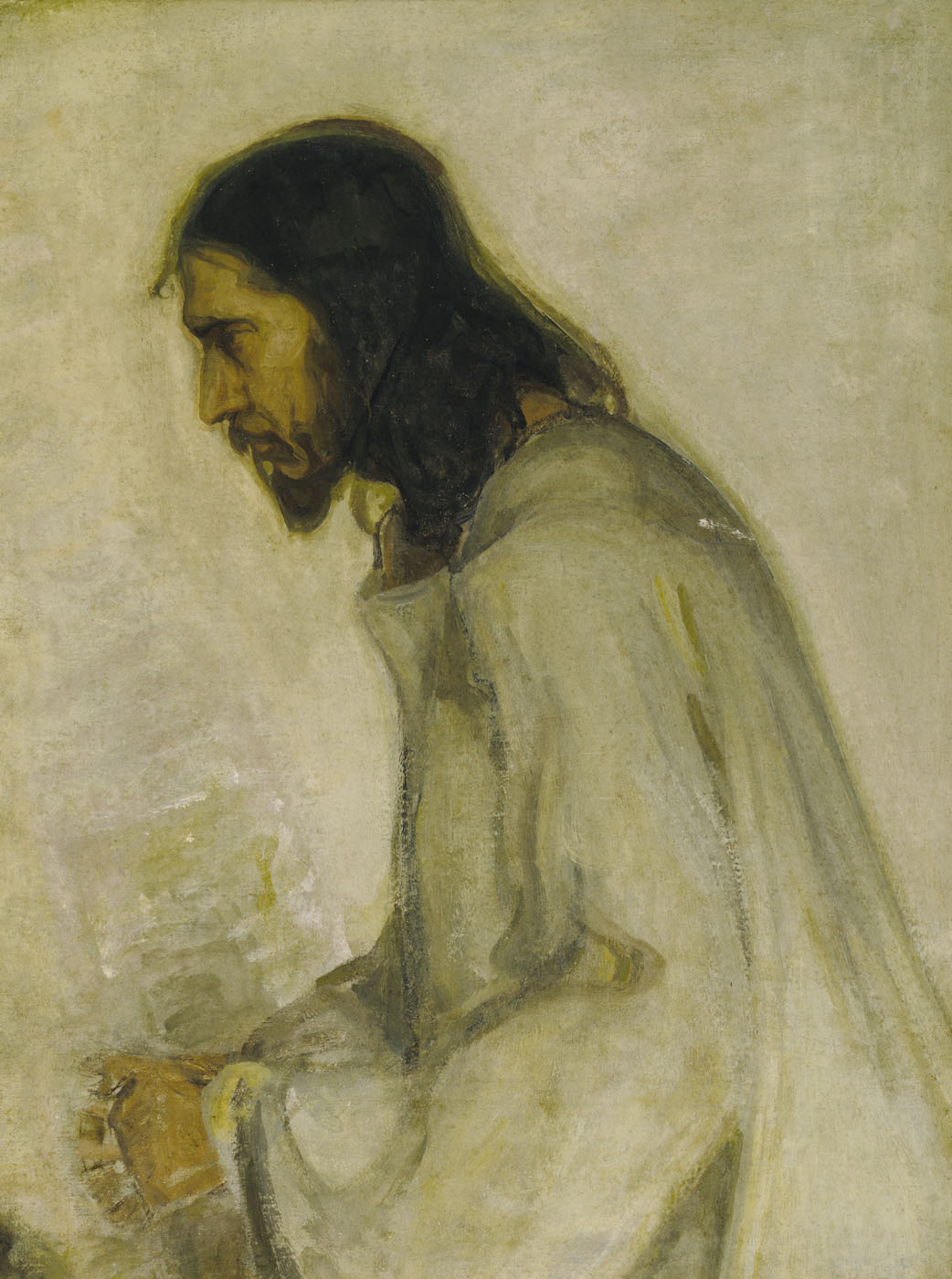

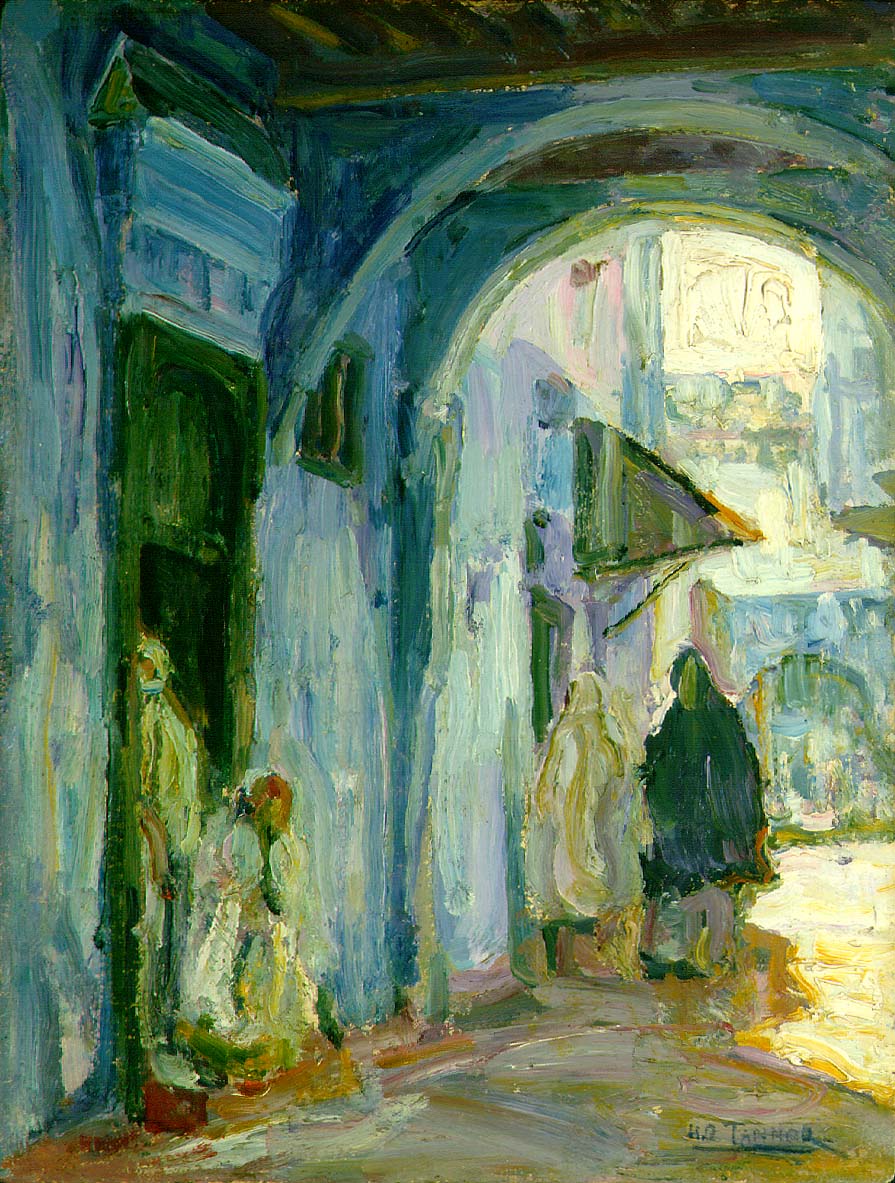

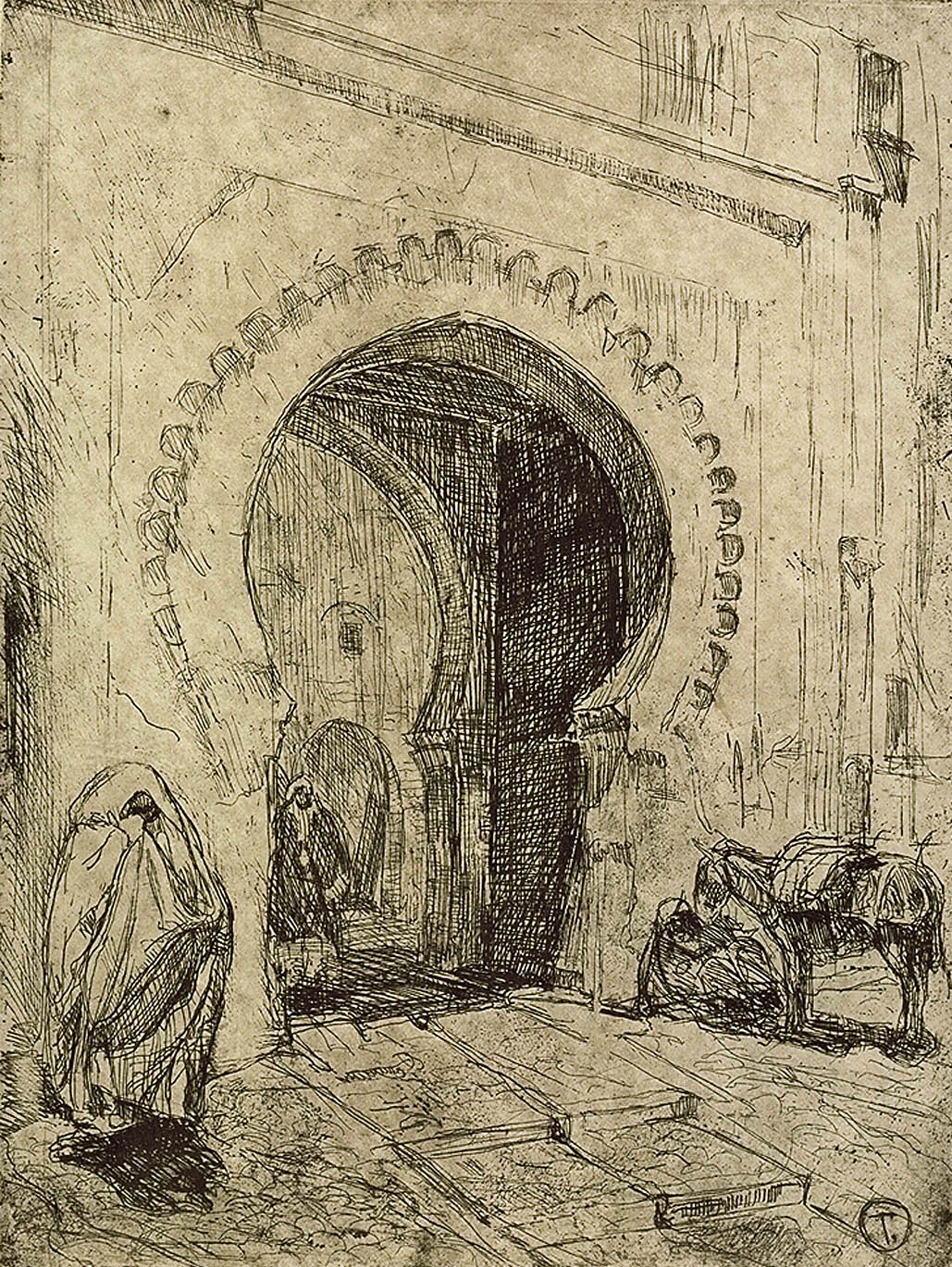

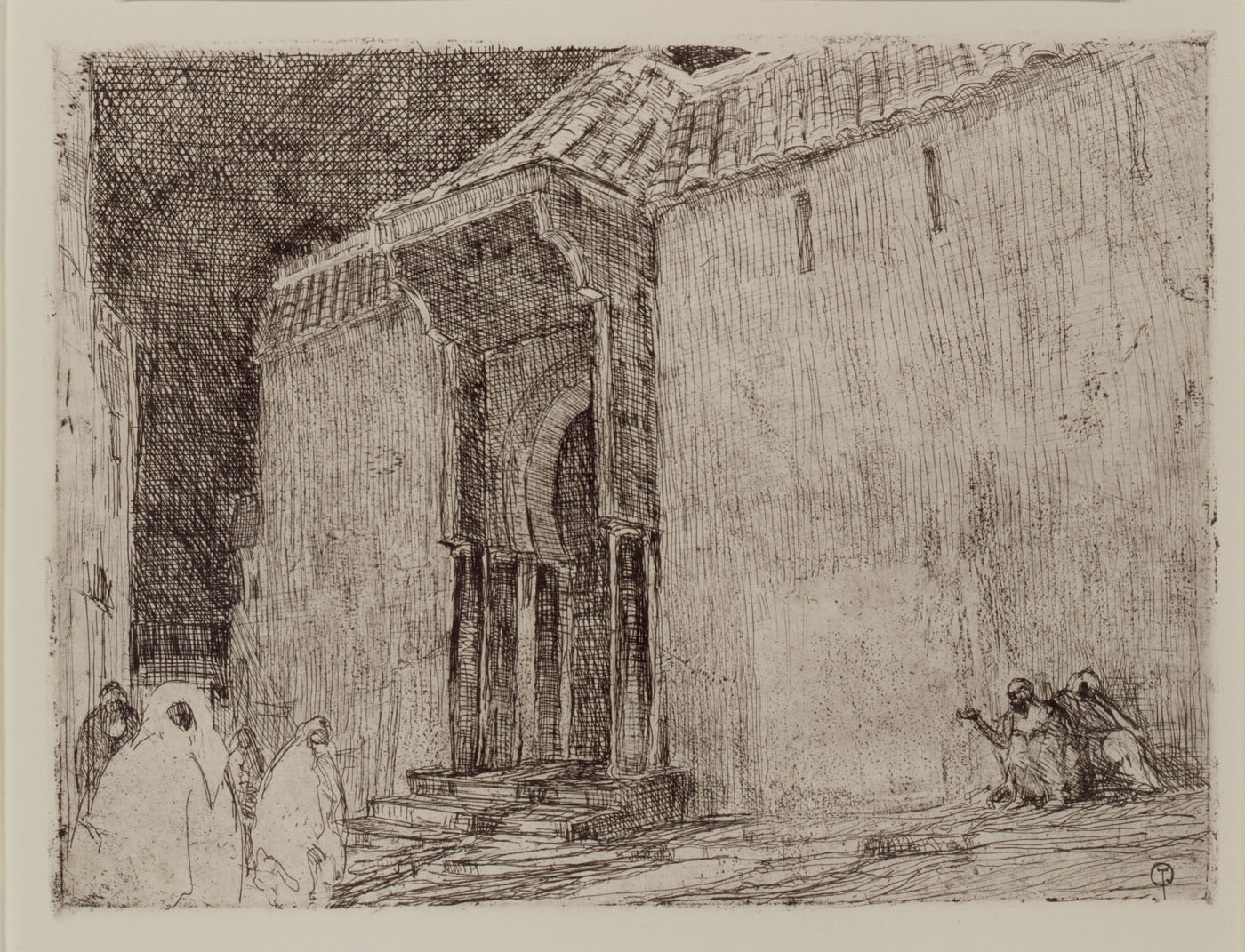

In 1895, Tanner painted Daniel in the Lion's Den, which won an honorable mention in the Paris Salon the same year. Two years later he completed Resurrection of Lazarus, which so impressed Rodman Wanamaker, a Philadelphia merchant in Paris, that he decided to finance the first of Tanner's several trips to the Holy Land. Before leaving, Tanner sent his Resurrection of Lazarus to the Paris Salon where it was awarded a third class medal and was purchased by the French government for exhibition at the Luxembourg Gallery and eventually entered the collection of the Louvre.

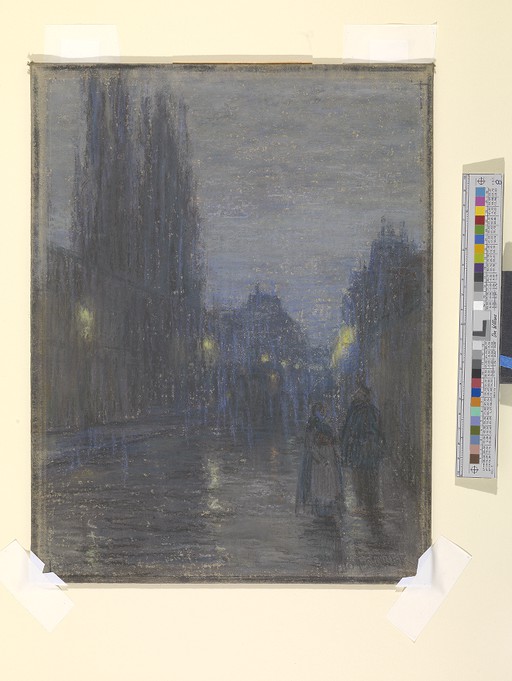

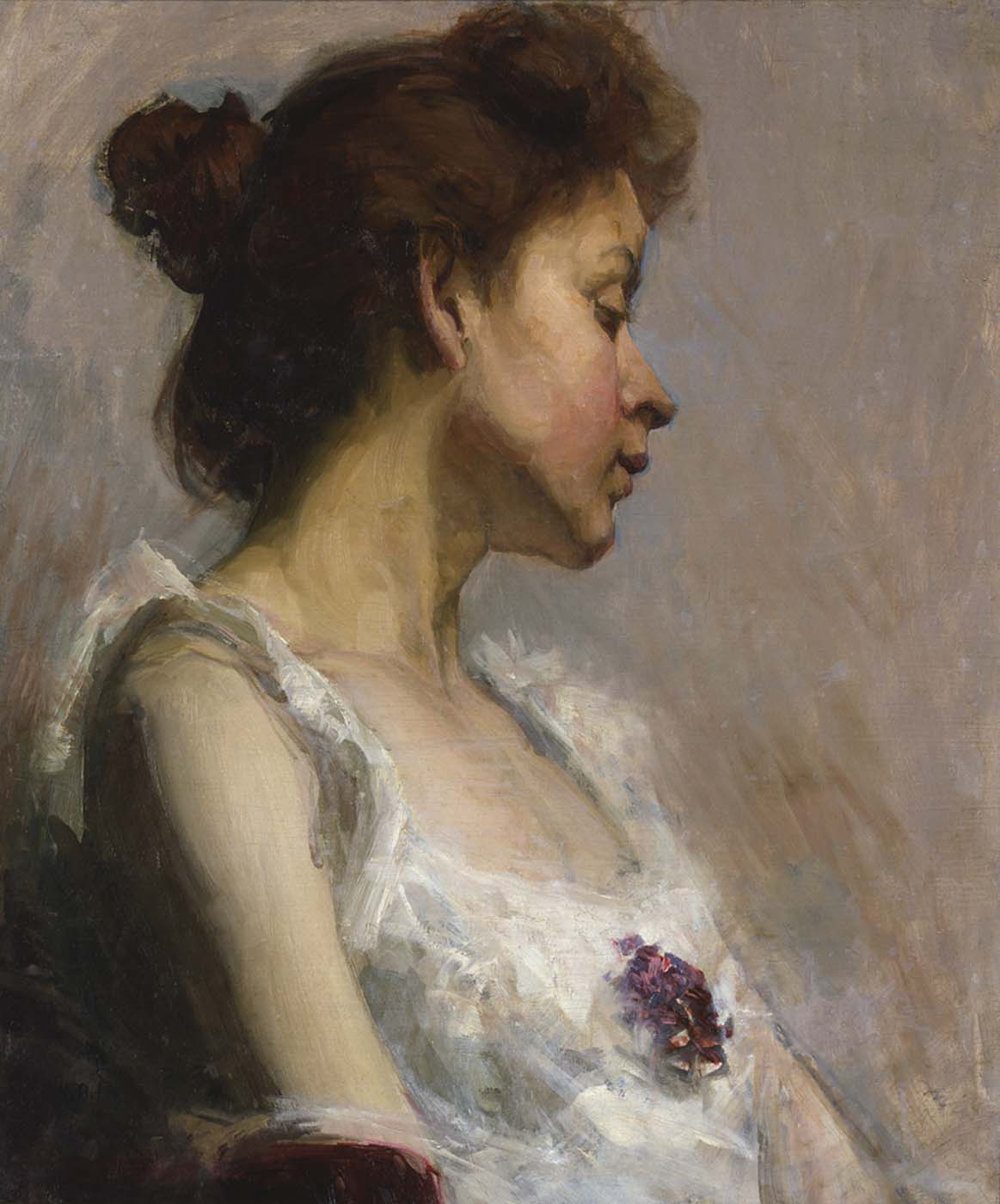

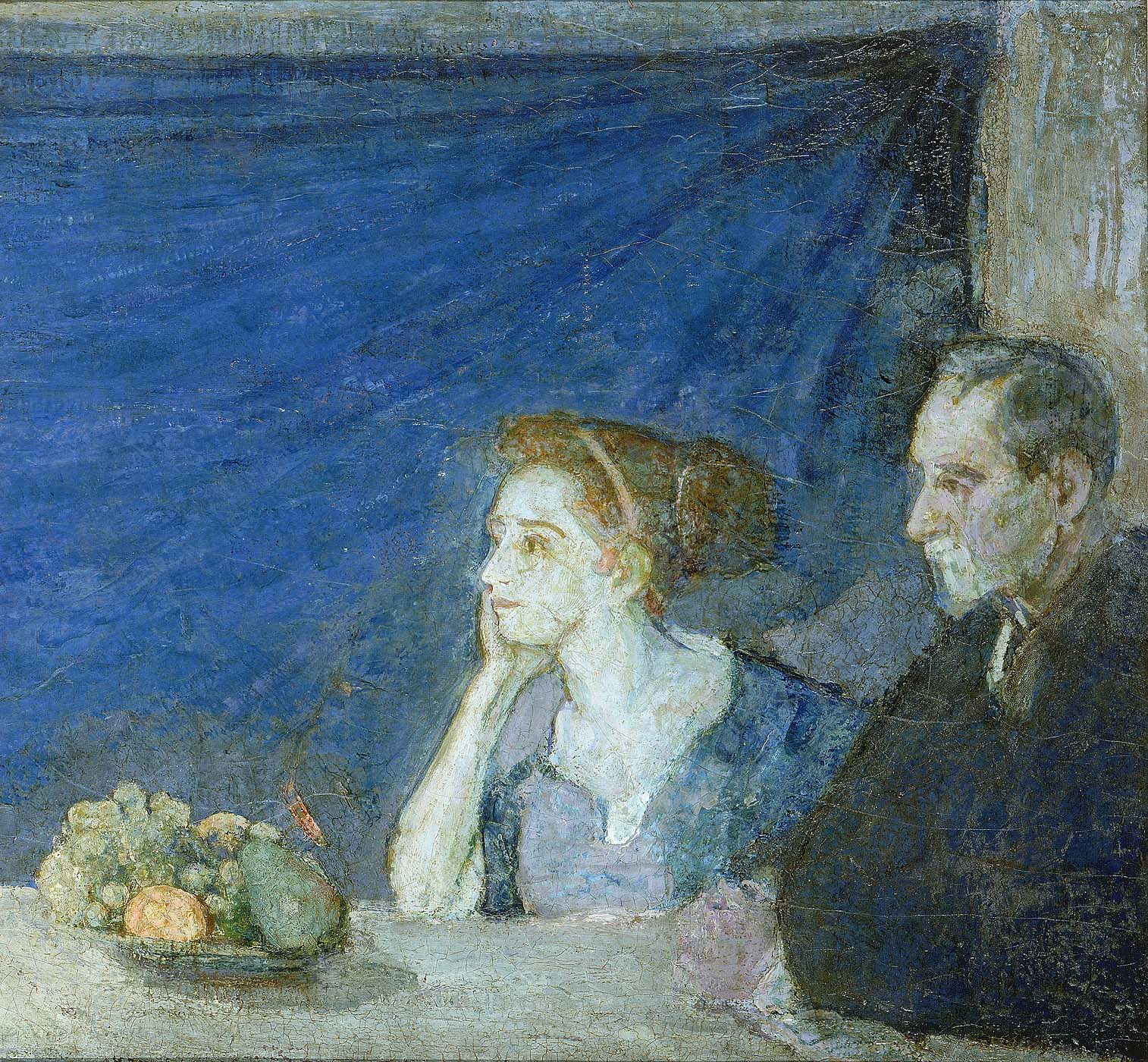

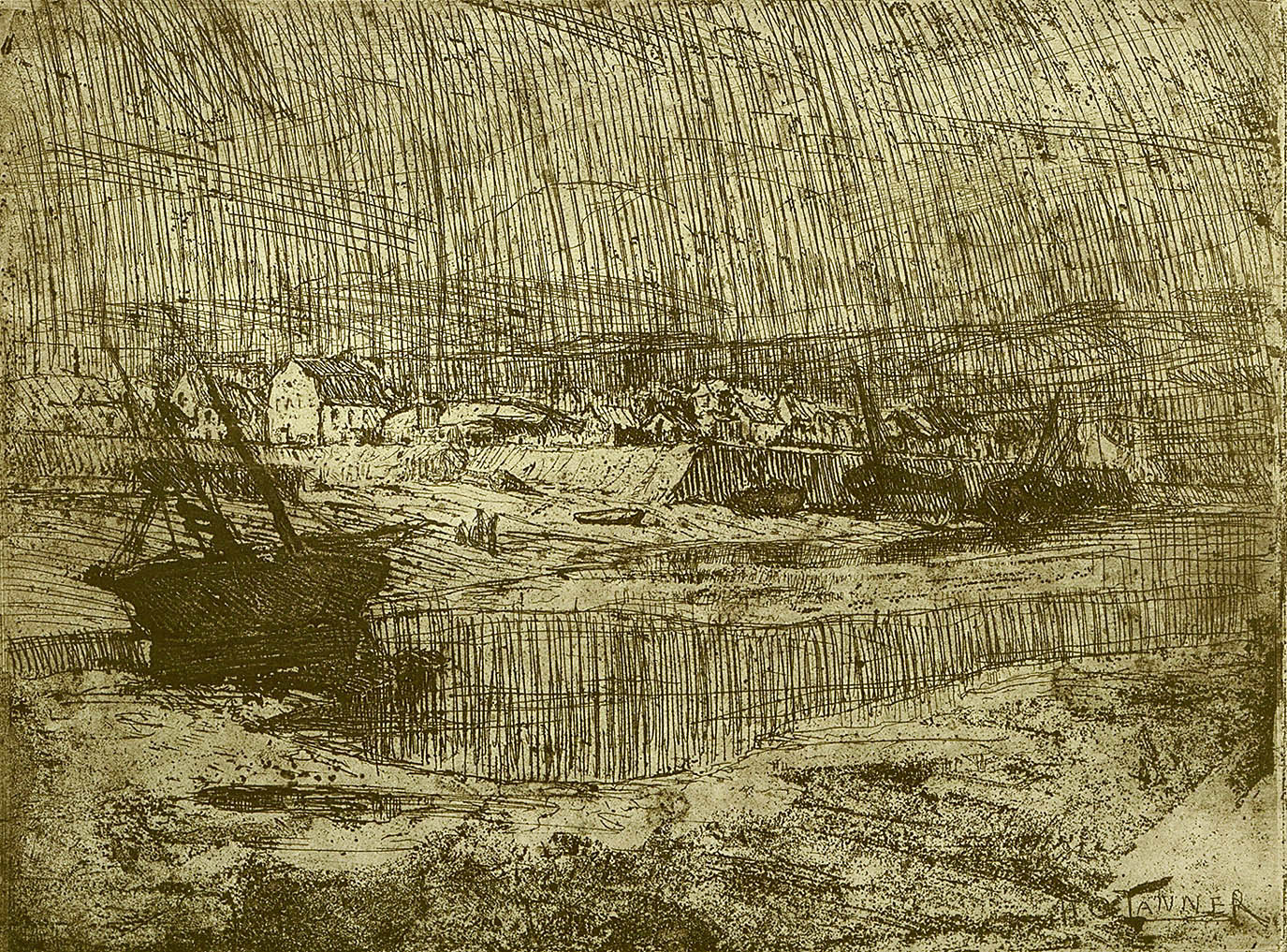

Spurred by his newly found acclaim, Tanner visited Philadelphia for several months in 1893. The visit, however, convinced him that he could not fight racial prejudice. Tanner returned to Paris and focused on painting religious subjects and landscapes. In 1899 Tanner married Jessie Olssen, a white opera singer from San Francisco, whom he had met in Paris. The couple's only child, Jesse Ossawa, was born in New York in 1903. Their marriage may have influenced Tanner's decision to settle permanently in France, where the family divided its time between Paris and a farm near Étaples in Normandy.

During the final decades of Tanner's career he enjoyed consistent acclaim. In 1900, his 1895 painting, Daniel in the Lion's Den, was awarded a silver medal at the Universal Exposition in Paris; the following year it received a silver medal at the Pan American exhibition in Buffalo.

In 1908 his first one-man exhibition of religious paintings in the United States was held at the American Art Galleries in New York. Two years later, Tanner was elected a member of the National Academy of Design. In 1923 he was made an honorary chevalier of the Order of the Legion of Honor, France's highest honor, and in 1927 he became a full academician of the National Academy of Design, the first African American to receive that honor. In his later years, Tanner was a symbol of hope and inspiration for African-American leaders and young black artists, many of whom visited him in Paris. On May 25, 1937, Tanner died at his home in Paris.

Regenia A. Perry Free within Ourselves: African-American Artists in the Collection of the National Museum of American Art (Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art in Association with Pomegranate Art Books, 1992)