Lenore Tawney

In 1954 Lenore Tawney abandoned sculpture for weaving and in the process, transformed the ancient craft of the weaver into a new vocation—fiber art. Following an intensely personal and experimental path, in the late 1950s Tawney created gauzy tapestries in which areas of plain weave were juxtaposed with laid in designs and large, transparent sections of loose, nonfunctional concept of weaving, her improvisational pieces appeared like freeflowing drawings made of colorful yarns floating in space.

Moving from Chicago to Manhattan in 1961, she became part of the avant-garde world of the abstract expressionists, and soon began to restructure her tapestries into sculptural 'woven forms.' These groundbreaking weavings dispensed entirely with a traditional rectangular format. In a startling departure from textile traditions, her tall, totemlike works were not set against a wall, but freely suspended in space. Often embellished with shells, beads, and fringes of feathers—and frequently composed of fibers of varying thickness and texture—these and other, smaller shieldlike designs woven in the 1960s, remained spiritually expressive, sculptural weavings.

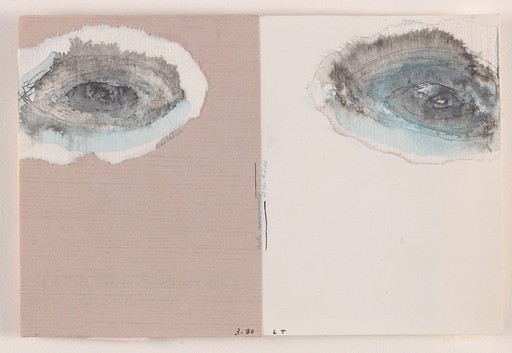

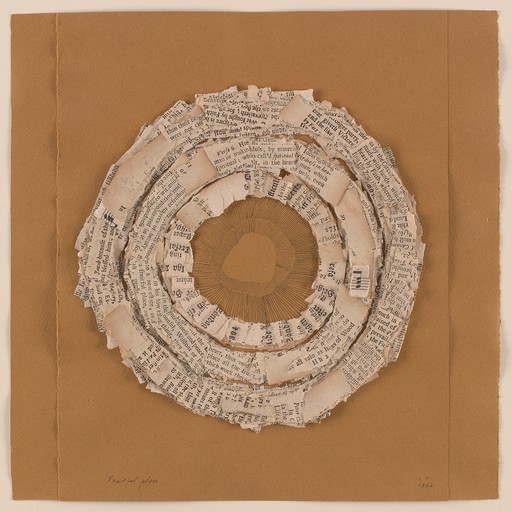

In 1964 Lenore Tawney created the first of a profusion of collages and assemblages made from found objects. After 1976, when she abandoned weaving altogether, these nontextile works became the primary focus of her art. Small in scale, the pieces were fashioned principally from pages taken from rare books and manuscripts on whose age-stained surfaces were affixed fragile birds' eggs and skeletons, feathers, small animal bones, shells, pebbles, corks, and wooden forms. Like her weavings, Tawney' s miniature collages display great sensitivity to the aesthetic properties of materials, but unlike the bolder woven works, they are intimate and quiescent pieces, containing elusive messages about the frailty and transiency of life, and the need to find inner peace.

Lenore Tawney has long been attracted to mystical religious philosophies from both the East and West, and has imbued all her work with a deeply felt spiritual content. Through her weavings and other art forms, she wishes to encourage an attitude of communion and contemplation. Extensive global travels have exposed her to a multitude of ancient cultures and religious traditions—especially those of India. Yet, she accepts the Zen concept that all things are connected. and indeed, in its entirety. Her art can be seen as an ongoing spiritual quest to express that intangible truth.

Jeremy Adamson KPMG Peat Marwick Collection of American Craft: A Gift to the Renwick Gallery (Washington, D.C.: Renwick Gallery, National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1994