László Moholy-Nagy

Laszlo Moholy Nagy came to the United States in 1937 to direct the New Bauhaus, an experimental school in art and design that was being established in Chicago. A prolific writer, as well as one of the most fertile experimental artists of his time, Moholy Nagy was a painter, photographer, filmmaker, builder of light space machines, teacher, and philosopher of new aesthetics. He believed that art offered a way to reorder society after the traumatic years of World War I, and he looked especially to technology to pave the way.

By 1937, when Moholy Nagy accepted the directorship of the New Bauhaus, he was well known in the United States through the exhibition of his work at various New York museums, through his book The New Vision (the English language edition of which appeared in 1930), and through the various articles he had published in Cahiers d'Art. On arriving in Chicago, Moholy Nagy wrote his wife Sybil of the "strange town it is no culture yet, just a million beginnings." Just two weeks later, Chicago captivated him: "There's something incomplete about this city and its people that fascinates me; it seems to urge one on to completion. Everything seems still possible. The paralyzing finality of the European disaster is far away."(1) Although the New Bauhaus failed for lack of financial support, in January 1939 he opened the School of Design (later called the Institute of Design), which was specifically "founded on the principles and educational aims of the Bauhaus."(2)

At first the School of Design's financial struggle seemed constant. But, it soon affiliated with the Illinois Institute of Technology, and Moholy Nagy remained at the helm until his death from leukemia in 1946. Ironically, that was the year that returning servicemen on the GI Bill finally brought economic stability to the institution.(3)

A Hungarian, Moholy Nagy served as an artillery officer during World War I. In 1918, he received a law degree from the University of Budapest and four years later met Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius. Gropius was impressed with the young Hungarian's art and his progressive ideas about its potential for improving society. Gropius invited Moholy Nagy to replace Johannes Itten, who had resigned as director of the Vorkurs in 1923. Josef Albers was already there, teaching the experimental preliminary course, when Moholy Nagy arrived.

Moholy Nagy joined the Bauhaus at a moment of heated debate over the school's program. Gropius envisioned the Bauhaus as a school of industrial design, in which the arts and industry would merge. In his plan, students would contribute to improving the modern world by designing beautiful, functional objects that could be easily and inexpensively produced. New materials, made possible by technological advances, would be used for architectural design as well as for functional objects, and contribute to raising the standard of life for mankind.

However, not everyone within the Bauhaus was comfortable with these ideas. Itten disagreed with Gropius and left; Lyonel Feininger also opposed Gropius's promotion of the industrial arts. Nonetheless, the Bauhaus offered rich and exciting possibilities, and its faculty in 1926 included some of the most innovative thinkers of the day—Herbert Bayer, Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, Wassily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee, as well as Josef Albers, Lyonel Feininger, and Moholy Nagy. Moholy Nagy joined the proponents of the unification of art and industry, and with Walter Gropius, edited a series of fourteen books that defined the philosophical framework for the Bauhaus program.(4)

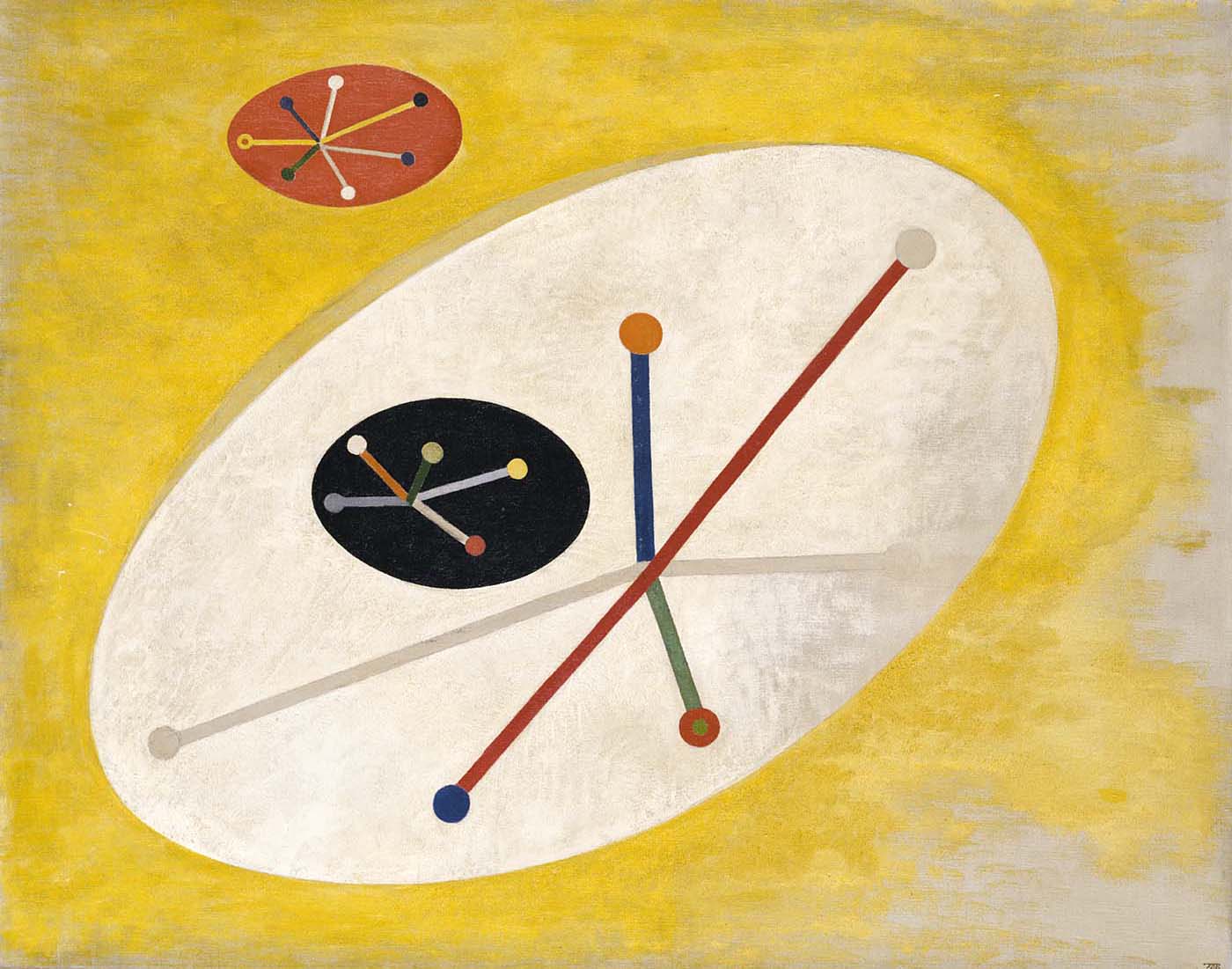

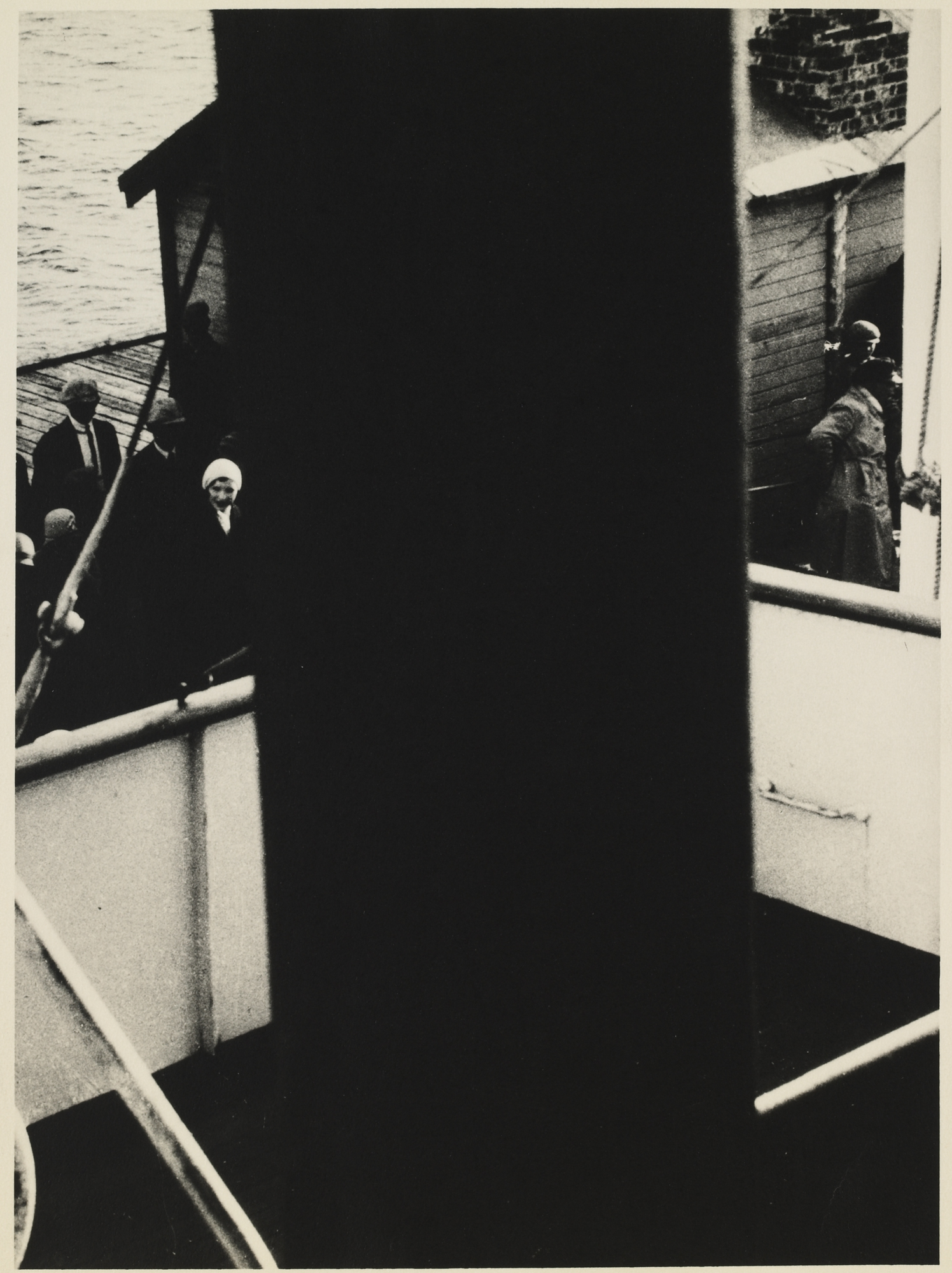

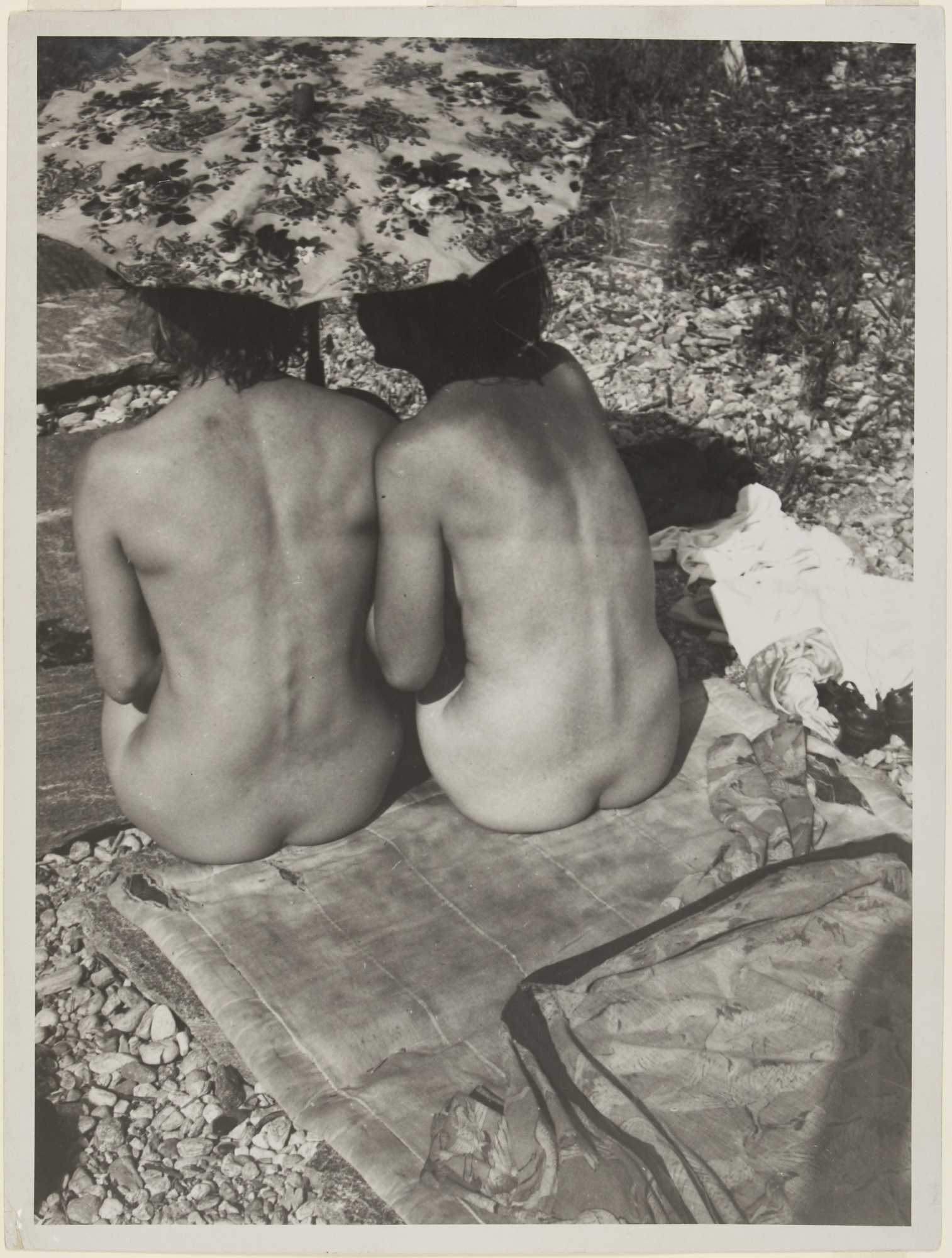

In 1928, in the face of increasing political pressure from outside, both Moholy Nagy and Gropius resigned. Moholy Nagy moved to Berlin, where he did stage design for the State Opera, the Piscator Theatre, and experimented with photography, film, and innovative graphic design. He spent 1934 doing advanced work with color film and photography in Amsterdam. The following year, he moved to London, where, in addition to making films, he published three volumes of documentary photographs. In 1935, he began making light space modulators—three dimensional "paintings" on transparent plastics, in which moving light sources cast changing shadows on etched and colored surfaces.

Moholy Nagy's early paintings reflected his youthful interest in German Expressionist painting. In the early 1920s, he met Kurt Schwitters and Paul Klee, and explored Dadaism. It was his contact with Russian Constructivism, though, that fueled both the style his art would take and his ideas about art's role as a vehicle for social change. Moholy Nagy, like Gropius, saw the machine as potentially dehumanizing and argued that the artist was uniquely capable of ameliorating its harmful potential. Yet Moholy Nagy took an essentially positive view of technology. He believed it offered opportunities for changing the world through mass production, distribution, and communication. He further believed that since art is rooted in society, the artist had a deep and abiding responsibility to address social issues. He saw the artist as a visionary—one who would provide the forms and ideas necessary for the understanding of future societies:

We need Utopians of genius to foreshadow the existence of the man of the future, who, in the instinctive and simple, as well as in the complicated relationships of his life, will work in harmony with the basic laws of his being.(5)

In 1939, Ilya Bolotowsky invited Moholy Nagy to join the American Abstract Artists, and he accepted with pleasure. Although he was unable to attend meetings or actively participate in the group's activities, Moholy Nagy exhibited annually and contributed a lengthy essay entitled "Space Time Problems in Art" to the 1946 Yearbook. When he acceptedmembership, though, he asked to be considered a painter and sculptor, rather than an architect of ideas, and generally showed paintings in the group's exhibitions.

1. Sibyl Moholy Nagy, Moholy Nagy: Experiment in Totality (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1950), pp.143, 145.

2. This note appeared on the school's letterhead. During World War II, when the shortage of industrial materials for household products became acute, Moholy Nagy's students experimented with a variety of alternatives for metal, including wooden bed springs, an infrared oven made of a garbage can for roasting meat, and string hung in doorways in place of screens. For a discussion of their often amusing contraptions, see Robert M. Yoder, "Are You Contemporary?" The Saturday Evening Post, 3 July 1943.

3. Moholy Nagy created special programs to accommodate students who had been wounded during the war. Exercises, such as texture charts to help the blind sharpen other senses, reflected the activities he had first developed for the foundation course at the Bauhaus.

4. For a discussion of the various viewpoints of Bauhaus staff, see Krisztina Passuth, Laszlo Moholy Nagy (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1980), pp.19–20. Lyonel Feininger, for one, remained unconvinced about the validity of uniting art and technology.

5. Joseph Harris Caton, The Utopian Vision of Moholy Nagy (AnnArbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press, 1984), pp. xvii–xviii.

Virginia M. Mecklenburg The Patricia and Phillip Frost Collection: American Abstraction 1930–1945 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press for the National Museum of American Art, 1989)