Ad Reinhardt

Ad Reinhardt was one of the few members of the American Abstract Artists who began his artistic career as an abstract painter. The son of socialist parents, Reinhardt also had leftist sympathies and belonged to the Artists' Union and the left wing American Artists' Congress. Yet throughout his life Reinhardt insisted that art was created and should be understood on its own terms, without reference to social, political, or literary ideas. "In the Thirties," he later declared, "it was wrong for artists to think that a good social idea would correct bad art or that a good social conscience would fix up a bad artistic conscience. It was wrong for artists to claim that their work could educate the public politically or that their work would beautify public buildings."(1)

At Columbia University he studied art history and aesthetics with Meyer Schapiro. By the time he graduated in 1935, Reinhardt was well versed in modern art movements, and had contributed Cubist inspired cover designs for a campus magazine.(2) He then studied painting at the National Academy of Design, and with Anton Refregier, Francis Criss, and Carl Holty at the American Artists School. Between 1936 and 1941, he was employed by the easel division of the WPA Federal Art Project and at the same time did free lance commercial art. One of his most important associations was with Russel Wright, the architect and industrial designer, for whom Reinhardt did cartoons and exhibits for the 1939 New York World's Fair. During the 1940s, he made posters for the War Bond drive, did artwork for the Office of War Information, designed promotional materials for the Columbia Broadcasting System, created baseball magazines for the Brooklyn Dodgers, and painted murals for the Café Society and the Newspaper Guild Club.(3) He was in the navy in 1945 and 1946 and served briefly aboard ship in Salerno Bay before the war ended. In 1947 he accepted a teaching post at Brooklyn College.

Reinhardt had a thorough understanding of the historical progression and philosophical bases of modern art movements. His gentle, but acerbic wit garnered public attention in 1946 with his humorous and now well known cartoons for the Sunday section of PM, a leftist tabloid founded by Marshall Field to provide a contrasting voice to the generally conservative New York press.(4) The most famous of these cartoons, How to Look at Modern Art in America, showed a large tree, its trunk labeled "Braque, Matisse, Picasso." At the juncture of various branches was a scale of abstract art to Social Surrealist art, with Mondrian (the most abstract) on one side,and George Grosz at the opposite end. The tree's branches bore leaves with names of artists whose work was in some manner related. The abstract branches reached skyward; those indicating social realists, Surrealists, and Expressionists were about to break from the effect of weights labeled "subject matter", "Mexican art influence", and "War Art".(5) Although the cartoon was a humorous evaluation, Reinhardt received letters from Sinclair Lewis, among others, thanking him for clarifying the interrelationships among modern artists.

Reinhardt joined the American Abstract Artists in 1937 at the invitation of Carl Holty: That was one of the greatest things that happened to me. All the great abstract artists—Mondrian, Léger and Albers—had come over, and then all the Americans that I admired—Holty, Diller, Balcomb Greene, Cavallon, McNeil and other post Cubist geometric abstractionists."(6) Reinhardt quickly became an active force within the organization, and in 1940, when the group picketed the Museum of Modern Art, ironically for showing the work of PM artists rather than the American avant garde, Reinhardt designed the broadside that presented the group's point of view.

His bold abstractions of the late 1930s, which Reinhardt called his "late classical mannerist post cubist, geometric abstractions," showed evidence of a sophisticated understanding of abstract composition.(7) He worked in collage as well as paint, bringing to this medium an all over compositional approach that signified his imminent move toward pure geometric structure. The Untitled painting of 1940, with its overlapping strokes of color, provides a painted parallel to the collages of the late 1930s. Yet his work retained clues to those artists he most admired. The optical energy of Red and Blue Composition (1941) owes a debt to the jazzy syncopations of Stuart Davis, who became a sort of mentor to the younger painter, though Reinhardt had not yet abdicated rhythmic curvilinear forms that bespoke his appreciation for Carl Holty.

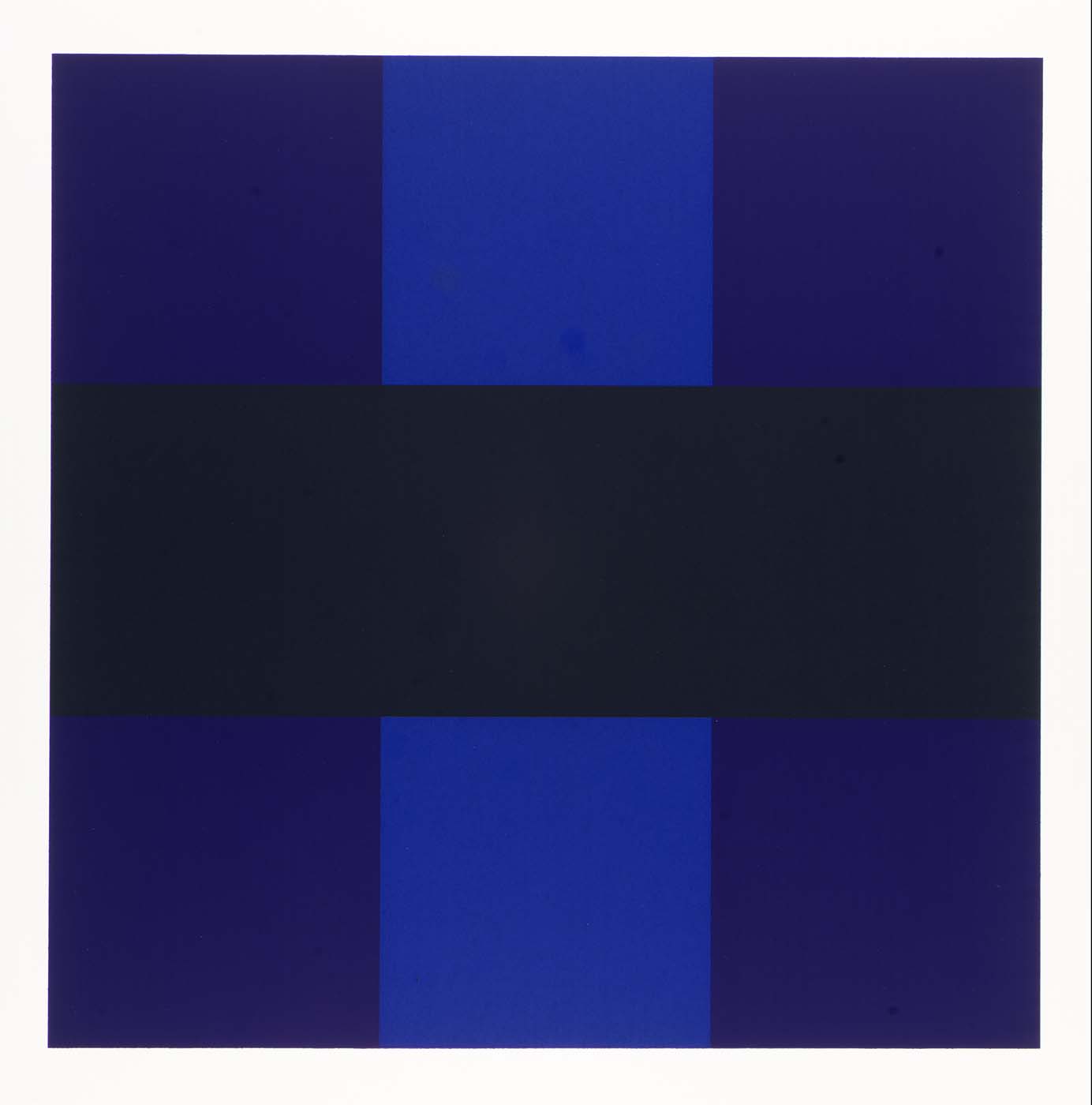

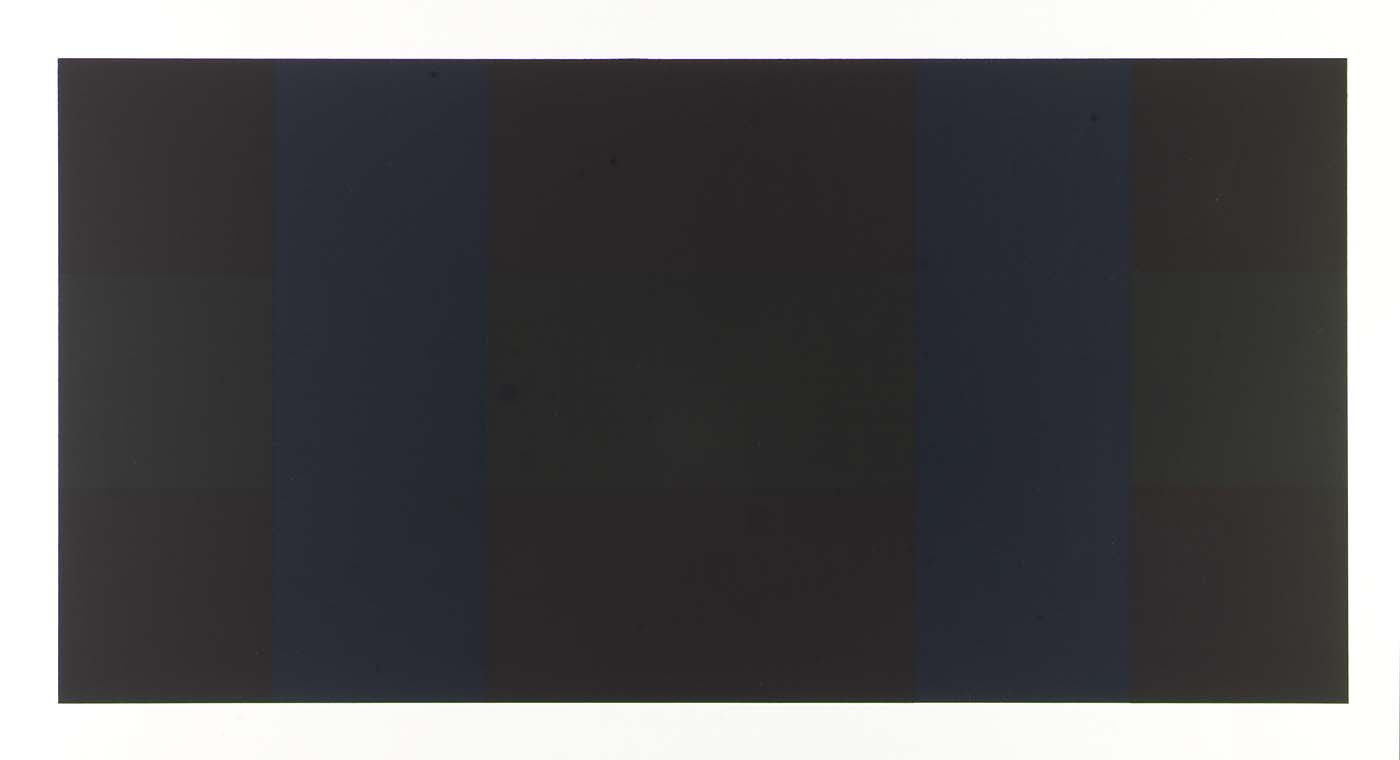

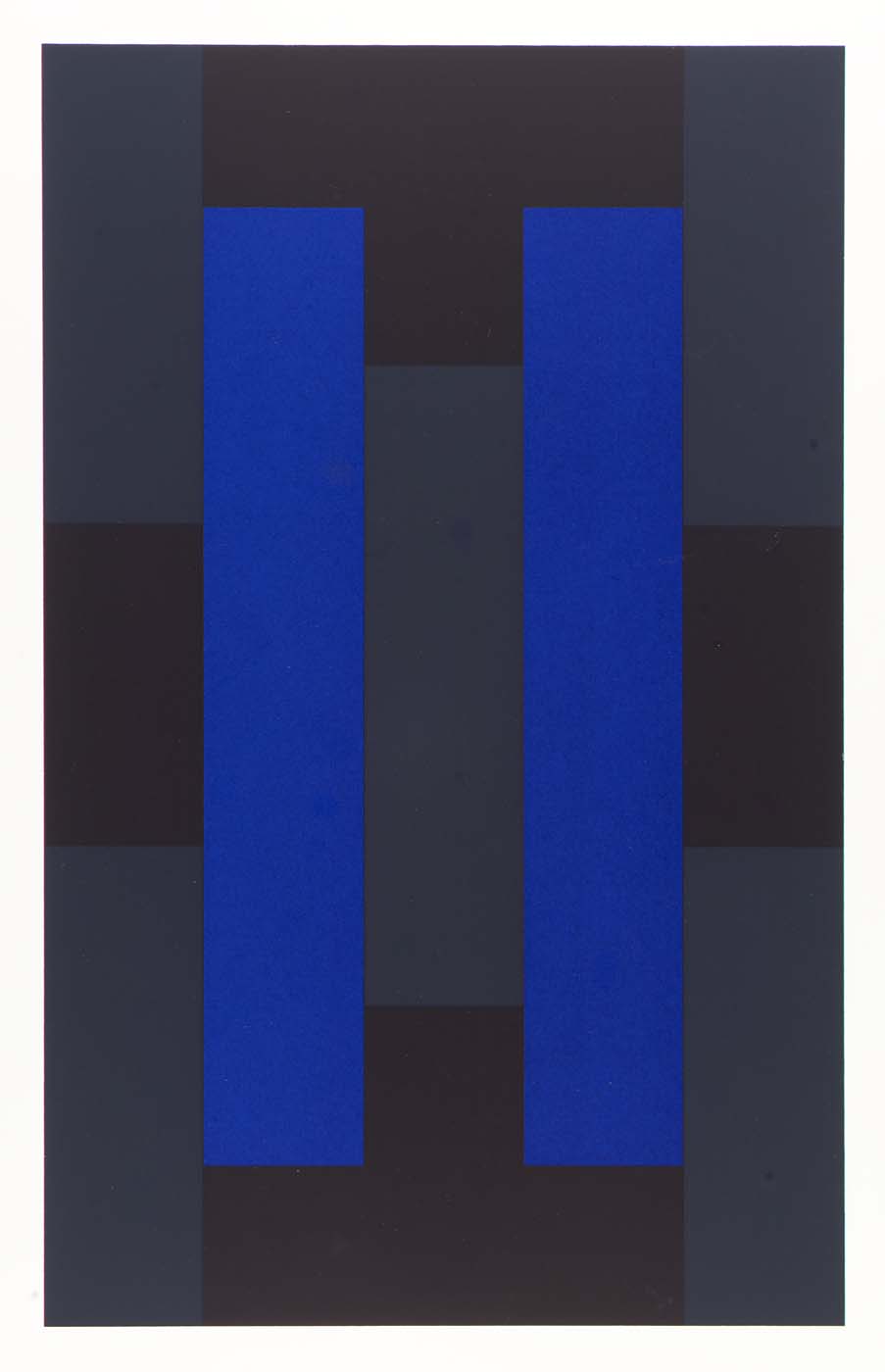

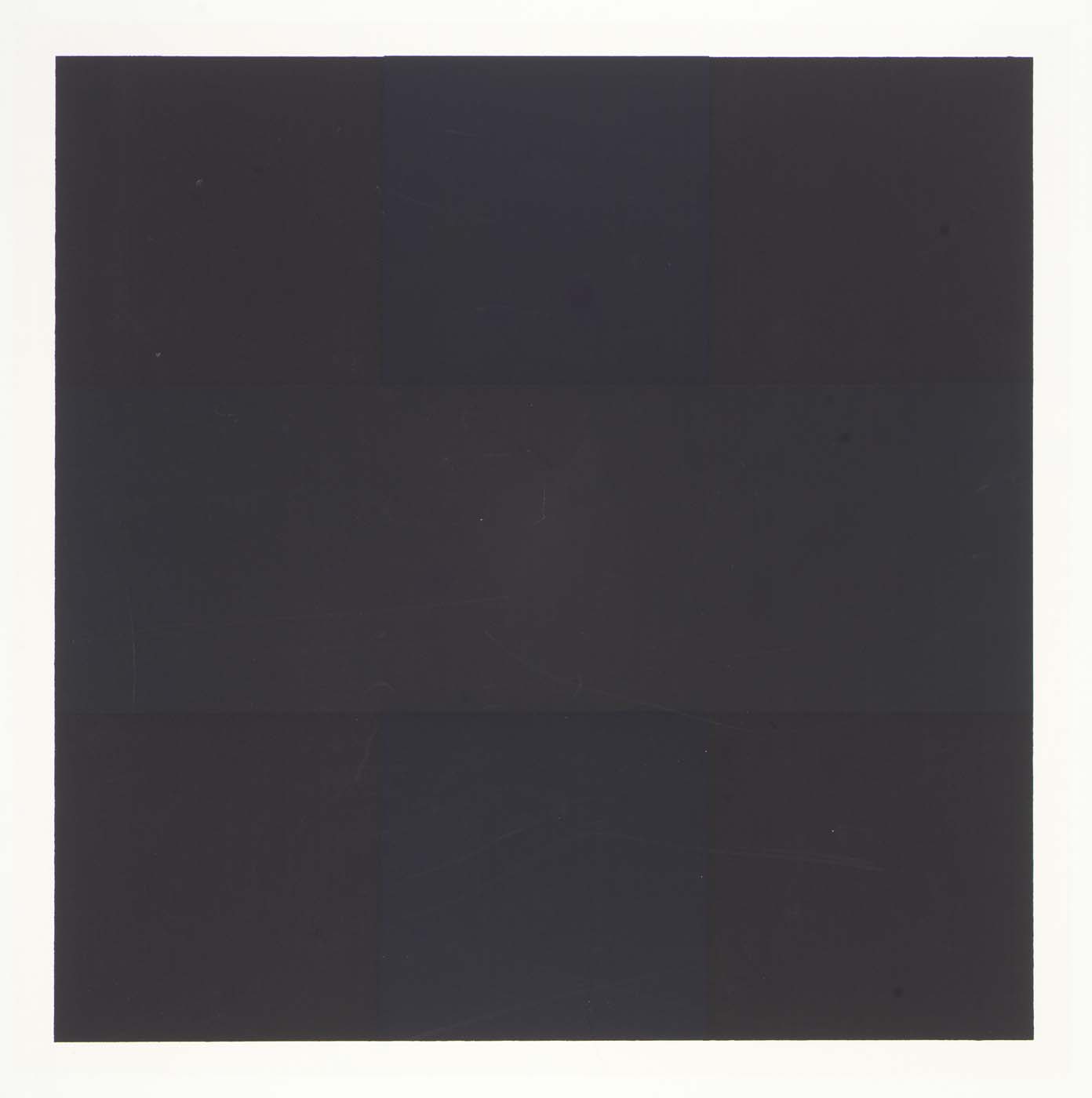

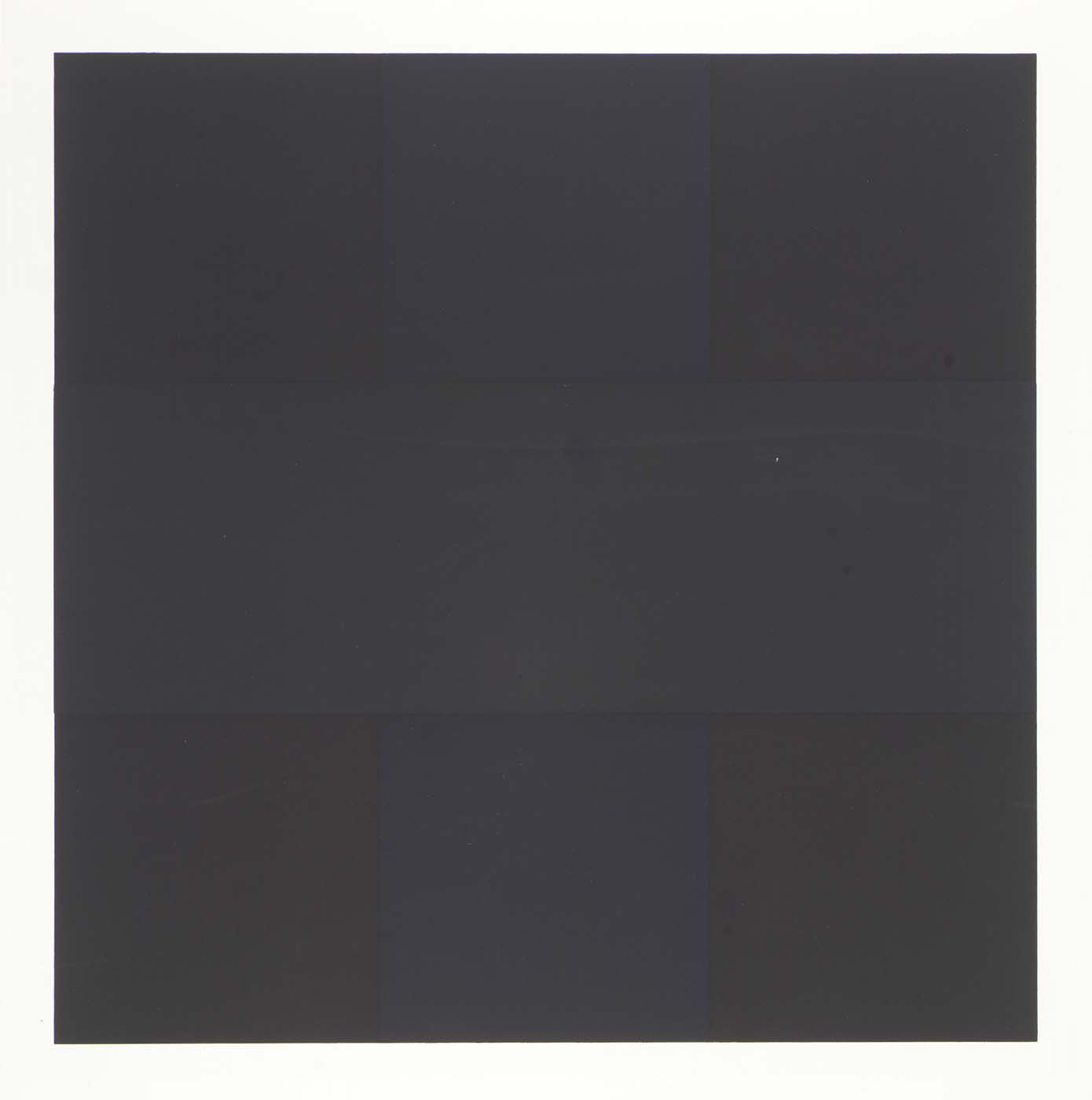

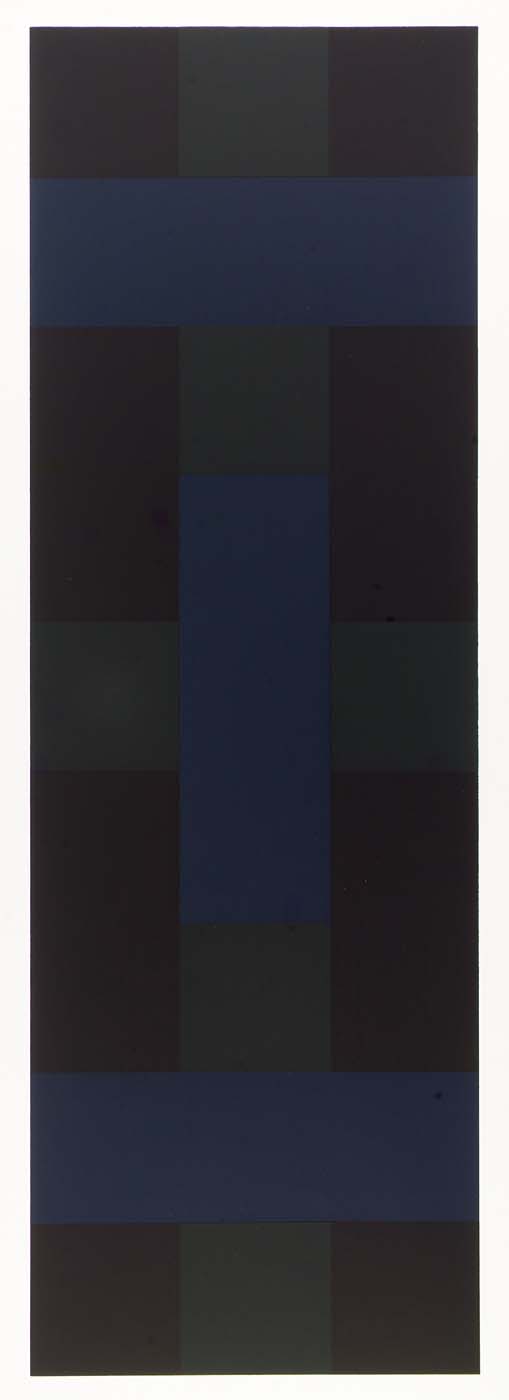

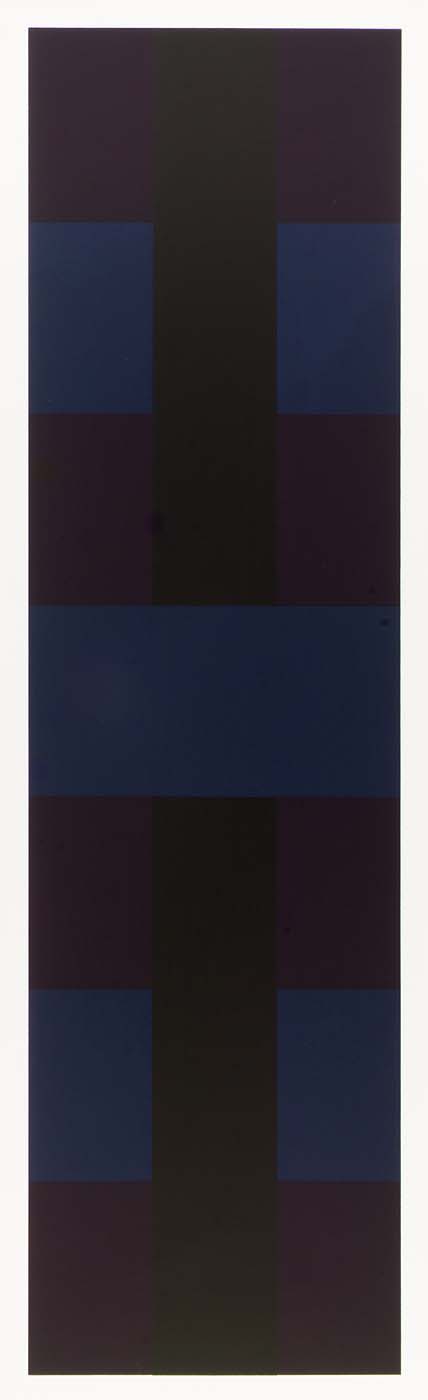

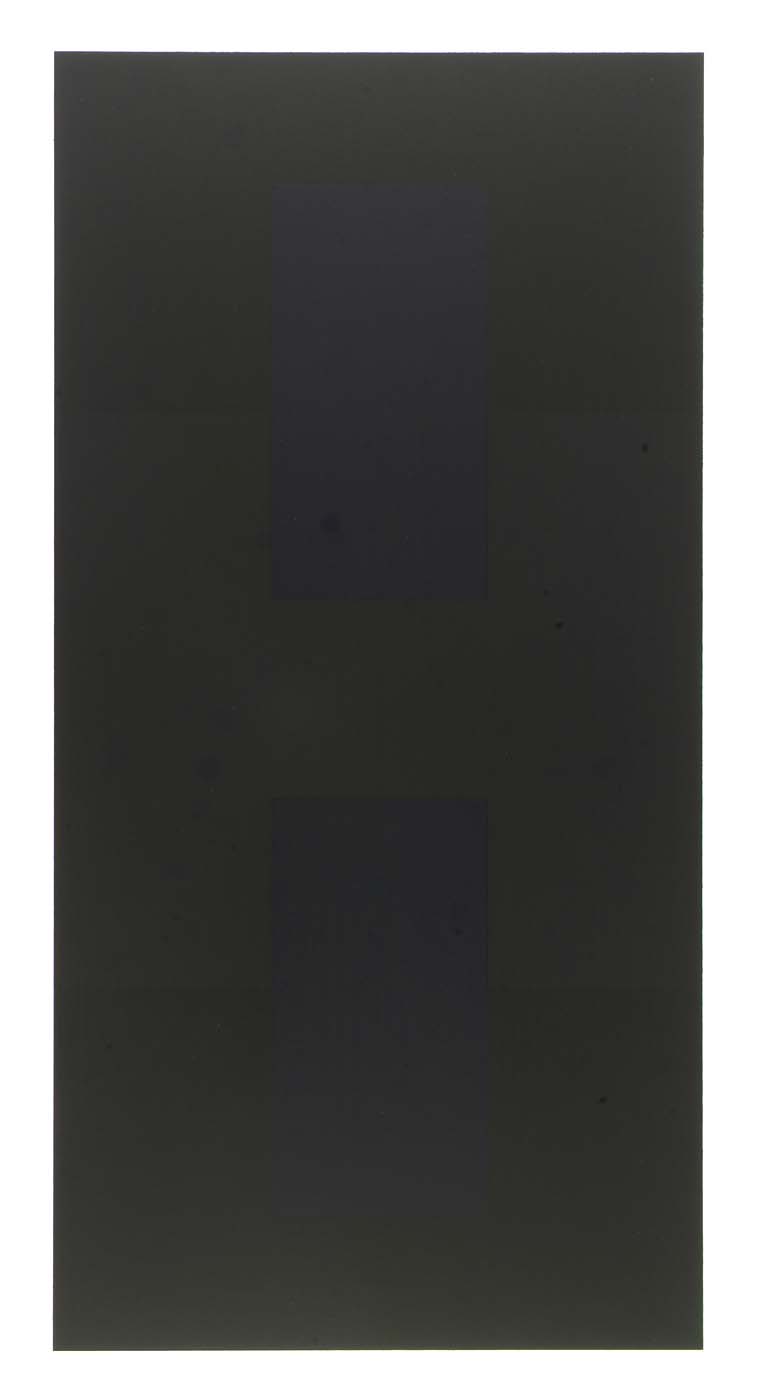

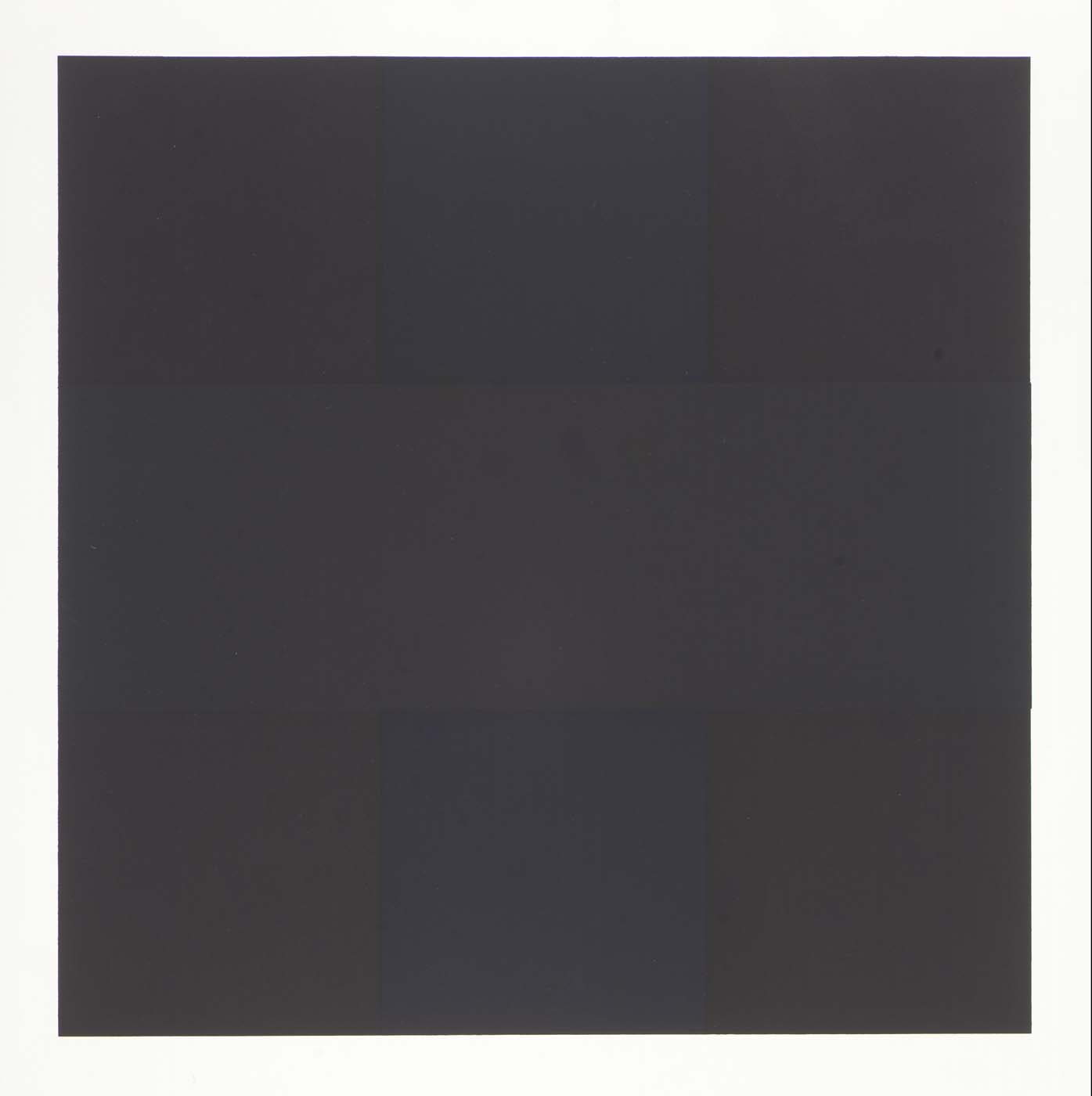

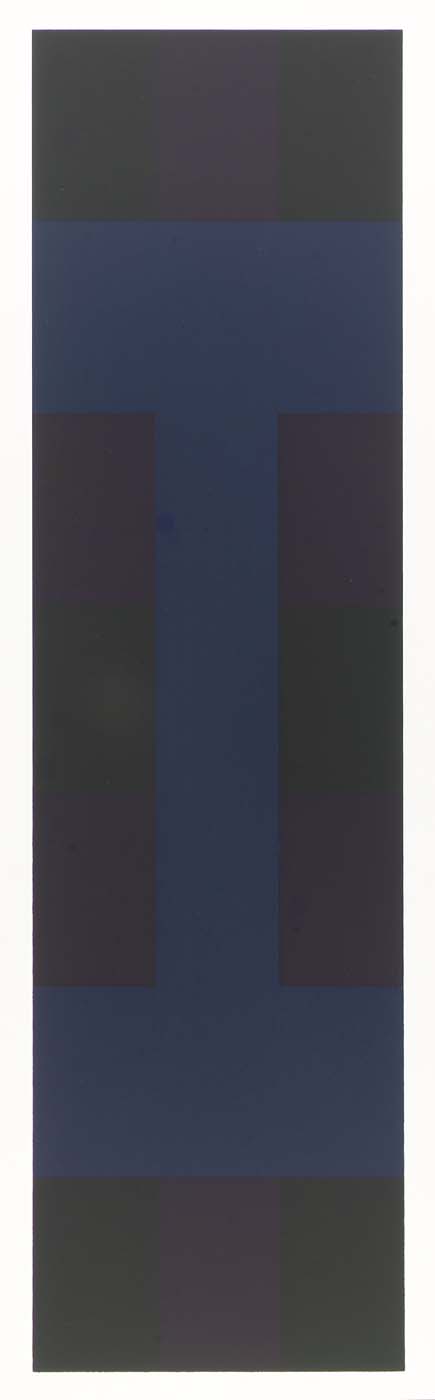

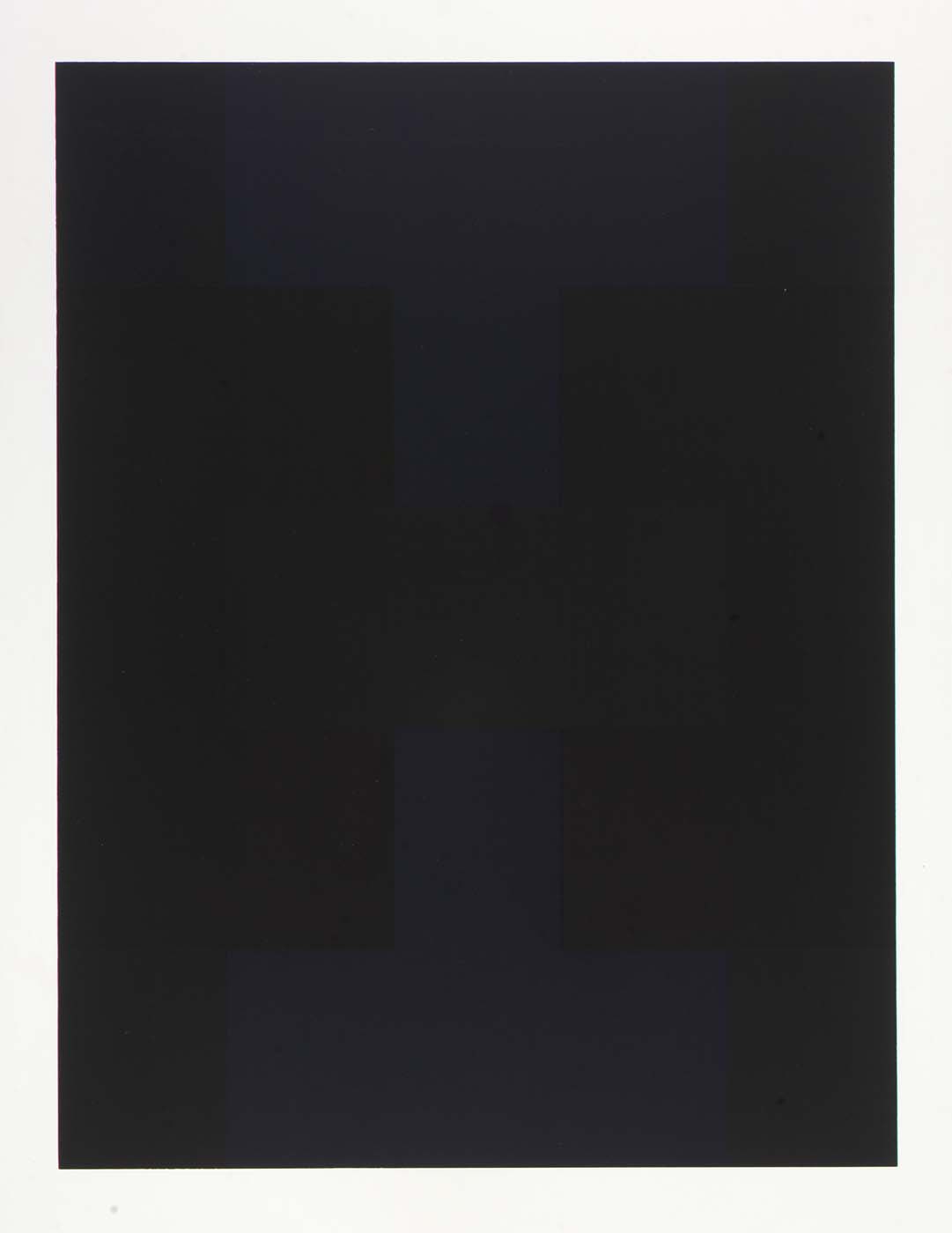

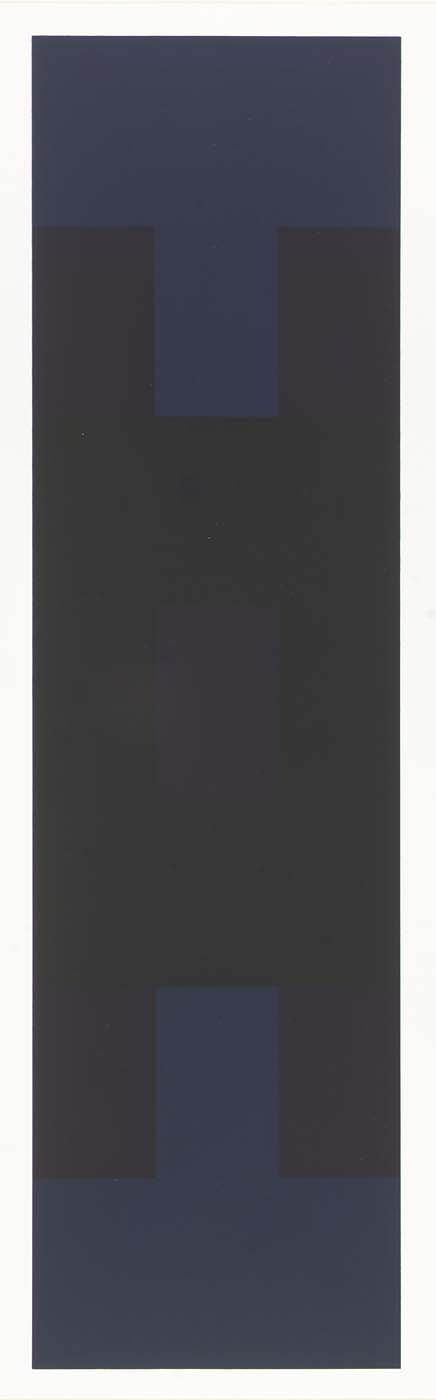

In 1941 Reinhardt began to break up the geometric structure of his paintings. By 1948, he was exhibiting compositions that replaced visual form with calligraphic, all over patterns that put him in an uncomfortable alliance with Abstract Expressionism. By the 1950s, however, he moved again toward strict geometric purity, creating symmetrical, rectangular shapes in single colors that reflected his early appreciation of geometric abstraction. From that time until his death in 1967, Reinhardt continued to simplify and purify his paintings—purging the bold colors and eventually arriving at his black paintings, the solemn, reductivist canvases for which he is perhaps best known.

1. See "The Philadelphia Panel," It Is, no. 5 (Spring 1960): 36.

2. See, for example, the cover of Columbia Review, April 1935, in Ad Reinhardt Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., roll N/69 100, which suggests familiarity with Francis Picabia's Cubist work of 1910 to 1920.

3. Reinhardt's list of commercial art credits is a lengthy one, which includes redesigning Macy's newsletter, book designs for major publishing houses, and designs for several trade associations. In 1944, he illustrated a children's book and did cartoons for Glamour magazine.

4. See Thomas B. Hess, "The Art Comics of Ad Reinhardt," Artforum 12, no. 8 (April 1974): 46–51, for a discussion and illustrations of Reinhardt's PM cartoons.

5. The original appeared in PM, 2 June 1946.

6. Quoted in Lucy R. Lippard, Ad Reinhardt: Paintings (New York: The Jewish Museum, 1966), p.15.

7. Reinhardt determined his own five stages. The first was "Late classical mannerist, post cubist geometric abstraction of the late 1930s." This was followed by "rococo semi surrealist fragmentation and "all over" baroque geometric expressionist patterns of the early 40s." Next came "archaic color brick brushwork impressionism and black and white constructivist calligraphies of the late 40's"; then "early classical hieratical red, blue, black monochromes square cross beam symmetries of the 50's"; and last, "classic black square uniform five foot timeless trisected evanescenses of the 60's." See "Five Styles of Reinhardt," handwritten list in Reinhardt Papers, Archives of American Art, roll N/69 100: 104.

Virginia M. Mecklenburg The Patricia and Phillip Frost Collection: American Abstraction 1930–1945 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press for the National Museum of American Art, 1989)

Selected Images of Ad Reinhardt

Objects at Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields (2)

Objects at Princeton University Art Museum (3)

Objects at Smithsonian American Art Museum (20)

Objects at Archives of American Art (57)