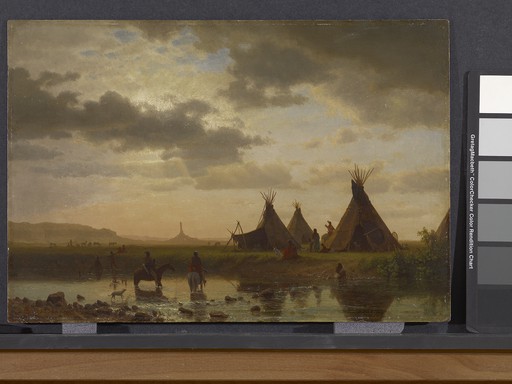

View of Chimney Rock, Ohalilah Sioux Village in the Foreground

Albert Bierstadt was one of the great mythmakers of the 19th century. The broader context for his remarkable contribution is the romance of the American wilderness, a narrative first enunciated in the early years of the century by Thomas Jefferson and Hector St. John de Crevecoeur, among others, and perfected during the time of Bierstadt’s greatest productivity between 1860 and 1880. At the center of that narrative is the notion that American republic is uniquely blessed with a natural setting that serves as an unparalleled spiritual and material resource for the new nation, a resource that would ensure its liberty and greatness in perpetuity.Bierstadt’s luminous landscape paintings, both great and small, are chiefly concerned with the spiritual values of wilderness. His works project a bewitching image of the American landscape, and especially the American West, as a place of the most intensely sublime beauty and grandeur. Bierstadt’s vision has a metaphysical, nearly religious quality; his nature is an Edenic paradise that radiates spiritual energy and restorative promise. Chimney Rock is one of a number of intimate portraits of Native Americans that Bierstadt produced in the wake of his trips to the intermountain American West in 1859 and 1863. Unlike his monumental canvases, these paintings are notable for their modest scale and for their central concern with human, as opposed to exclusively natural, subject matter. In the foreground of Chimney Rock, a small Ogillallah Sioux encampment is pitched peacefully on the banks of the North Platte River; in the distant background, Chimney Rock rises dramatically from the floor of the vast plain. The late afternoon sunlight is romantically golden and smoky, as in so many of Bierstadt’s paintings, and the light and airy vastness of the distant high desert landscape contrasts strongly with the warmer and darker tones of the foreground scene. In that scene, the central subjects of the piece, several Sioux adults and a half-dozen or so children, engage in languorous domestic activities—bathing in the stream, sitting by the river bank, preparing the evening meal. Chimney Rock and related works evoke a Rousseauian vision of Native American life. The Sioux encampment sits with perfect ease in the landscape; indeed, it seems to rise organically from that landscape. The scene has a distinctly domestic tone and conveys a profound sense of peace and tranquility. This is the uncorrupted social order that Rousseau imagined in his Second Discourse, a society deeply connected to the land and living a life of simple nobility, far from the refinements, complex needs, and dependencies of the eastern, urban world where Bierstadt painted and made his living. The irony of Bierstadt’s vision in Chimney Rock and similar paintings is notable. Bierstadt encountered and documented the Native American way of life just as it was entering its most intense period of apocalyptic demise at the hands of settlers and the armies that made way for them. Those settlers were drawn in part by the compelling economic opportunities of the western frontier, but some, perhaps many, were also drawn by the mythical allure of the western landscape, an allure that Bierstadt did so much to create and promulgate among restless Americans in the latter half of the 19th century.William D. Adams

- 0

- Other objects by this creator in this institution

- 69

- Objects by this creator in other institutions