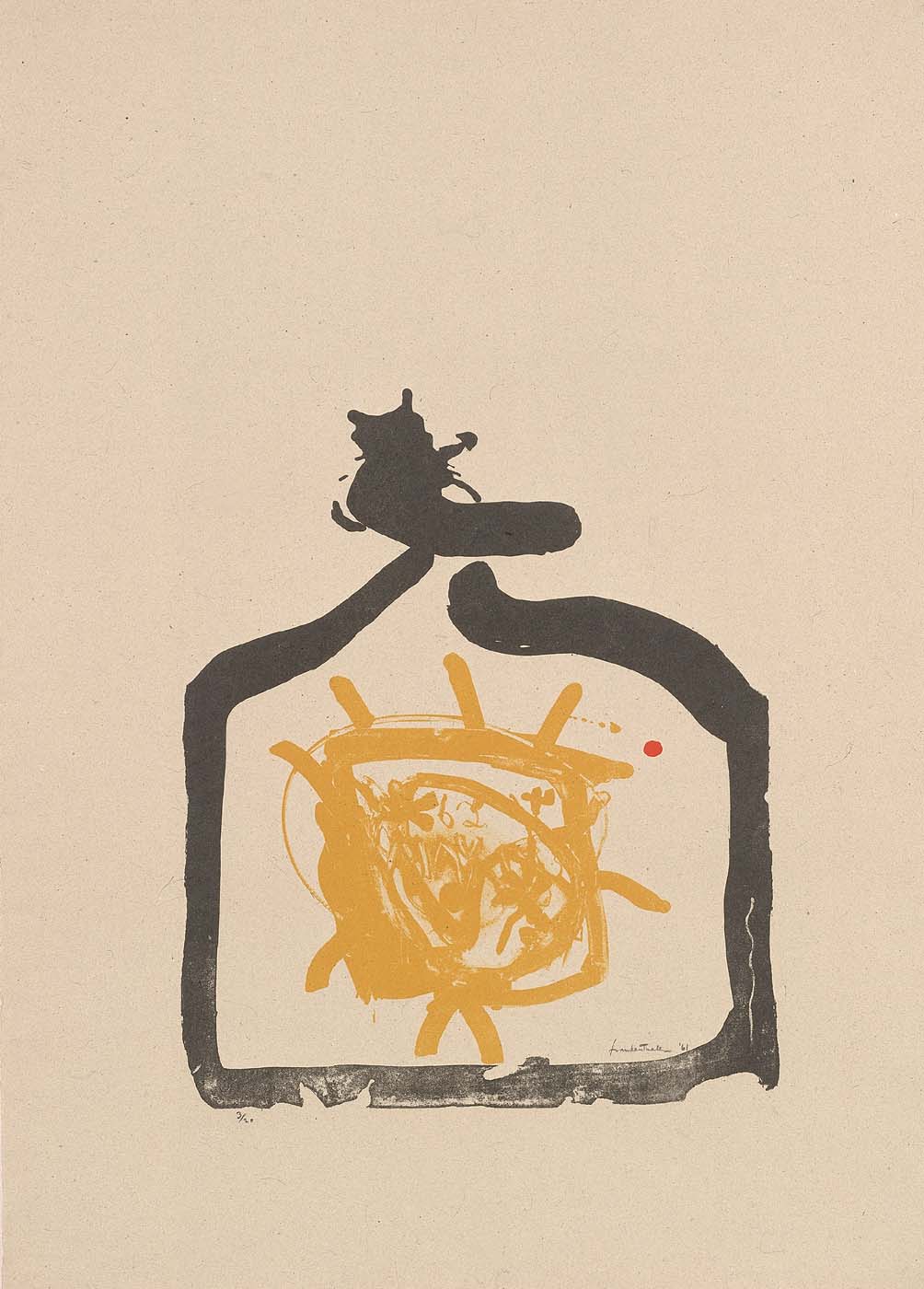

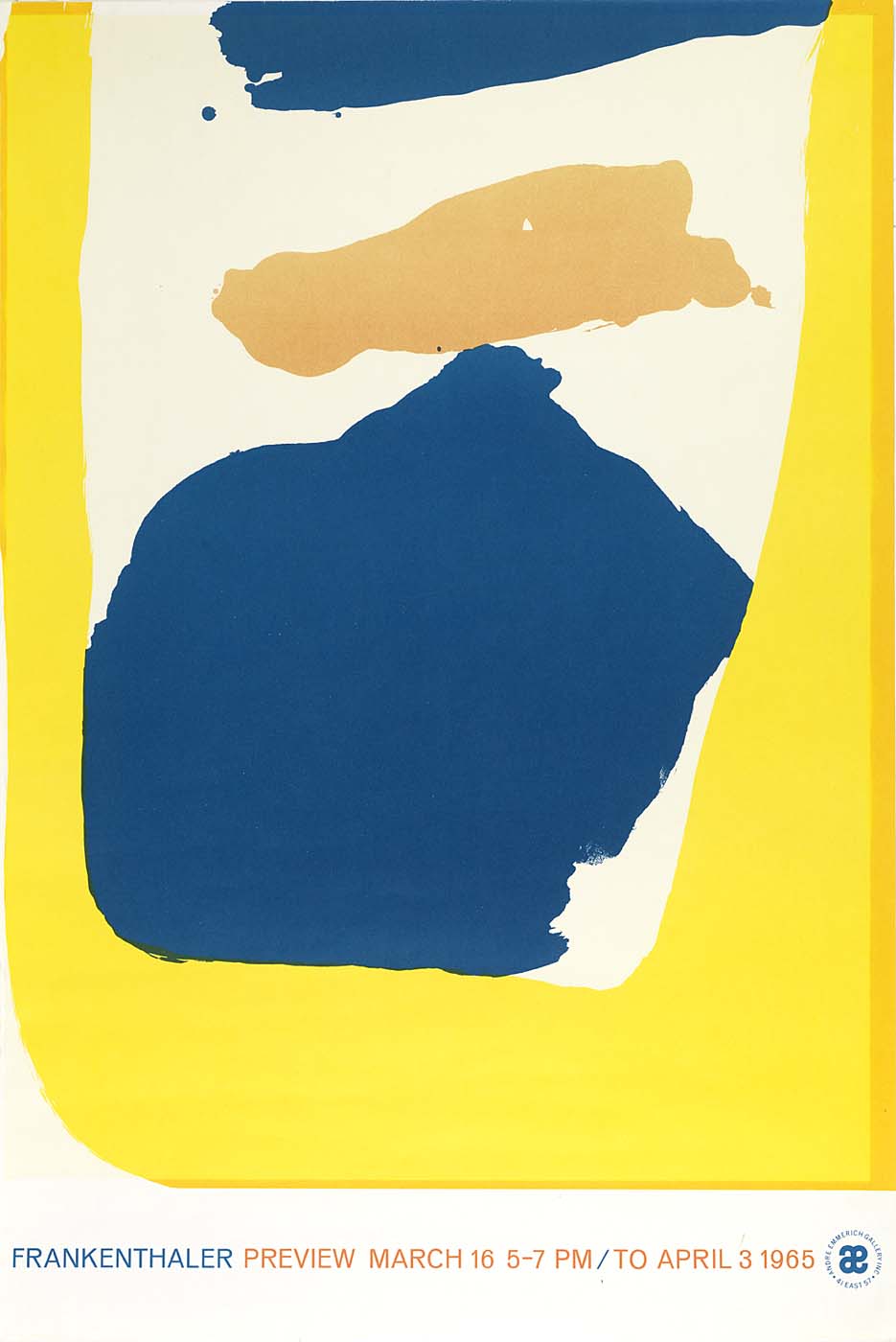

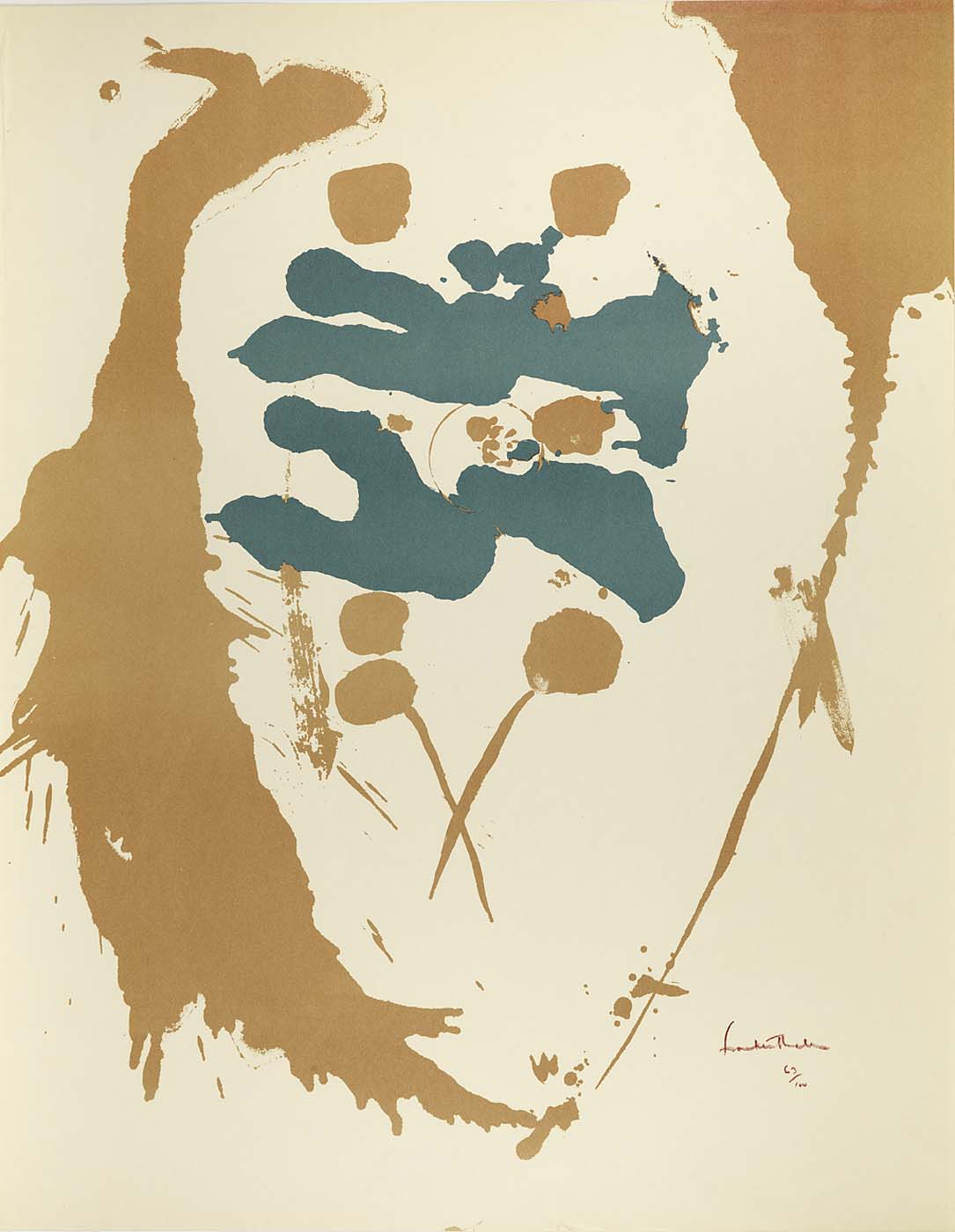

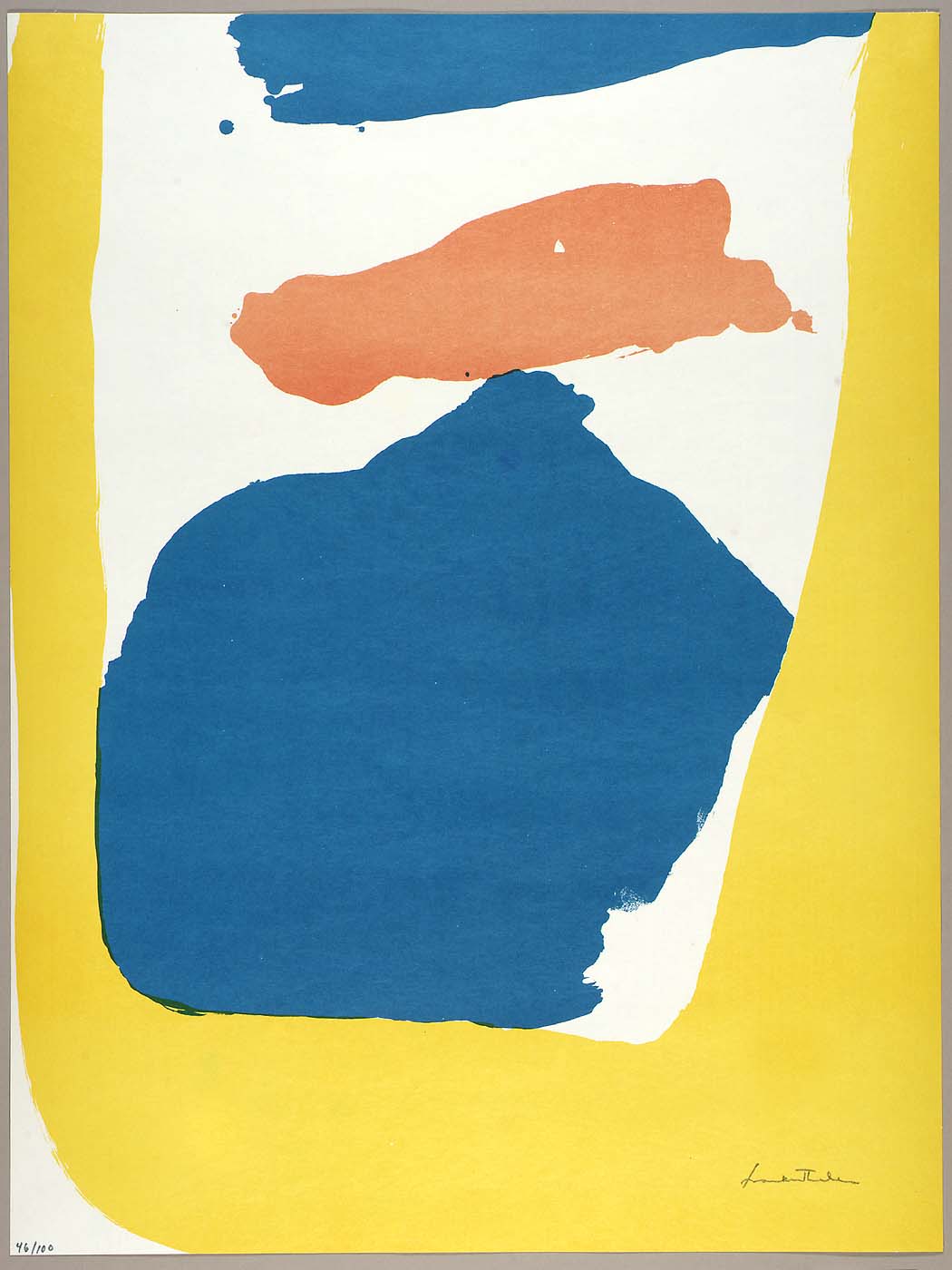

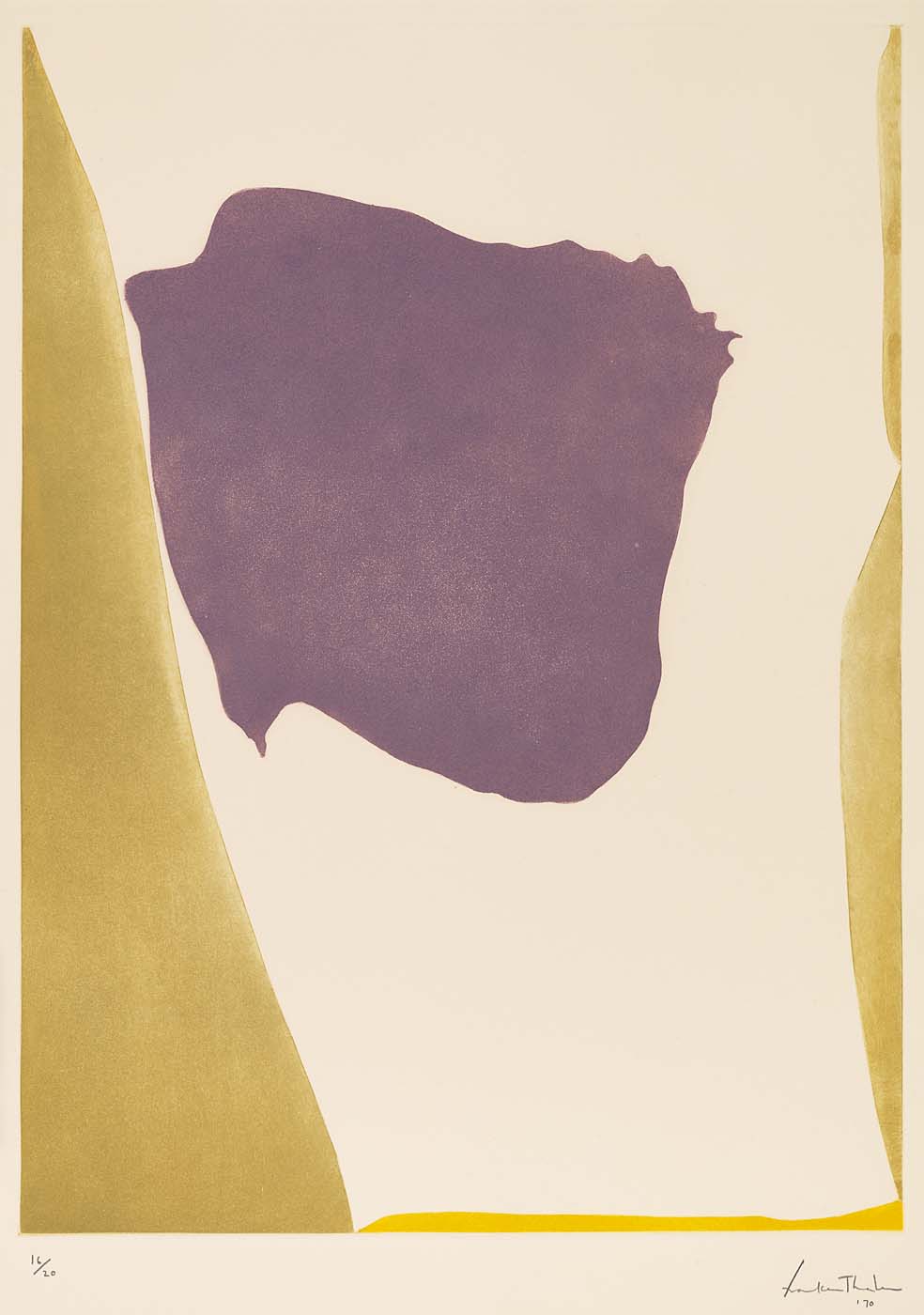

Helen Frankenthaler

Helen Frankenthaler's works helped redefine painting. From the Renaissance on, a painting was considered a window onto the world, through which one saw an illusion of reality. This concept was challenged intensely throughout the first half of the twentieth century, climaxing in the 1950s with the work of artists like Frankenthaler and Jackson Pollock.

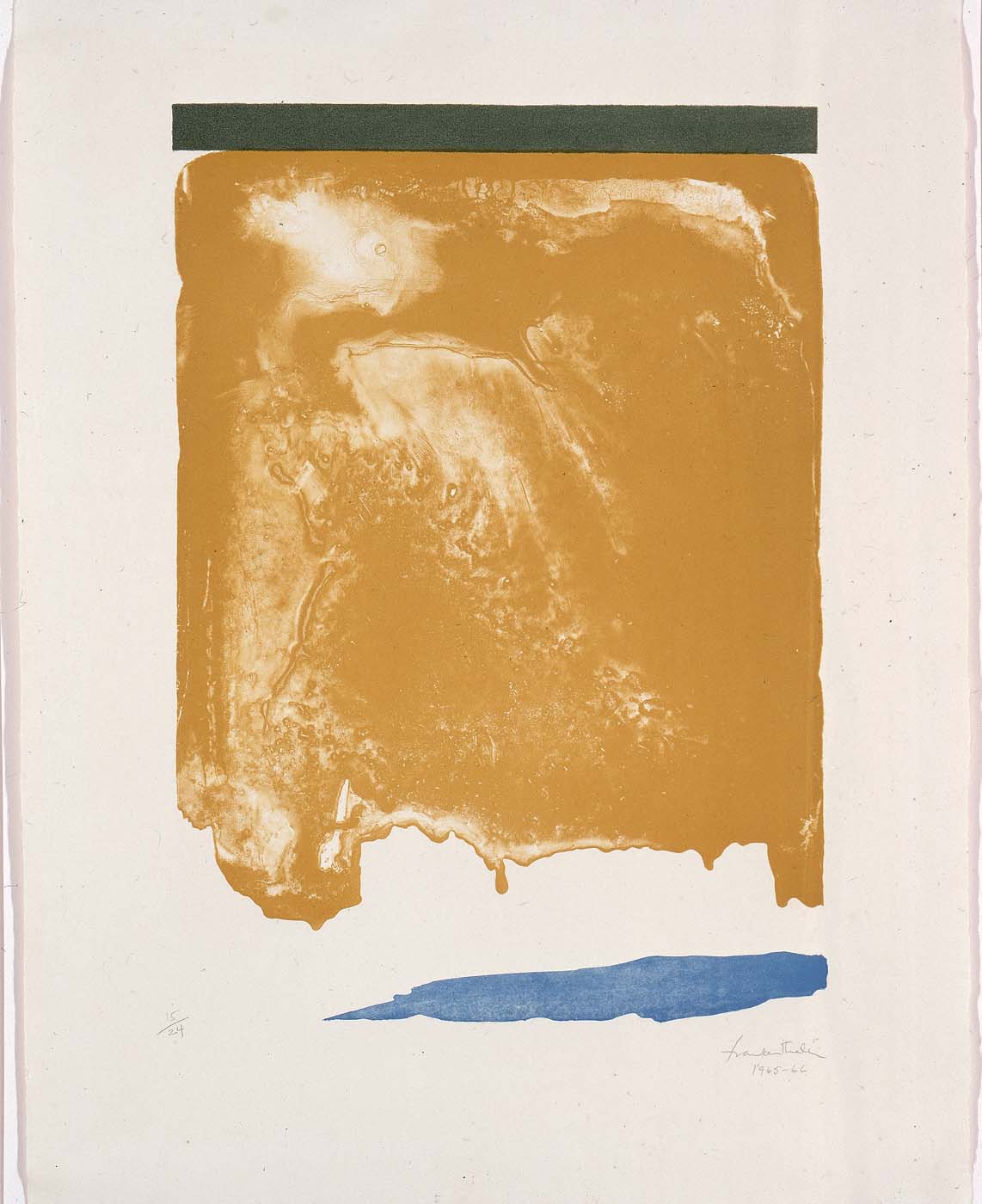

Frankenthaler returned home from college in 1949 to her native New York, the city producing the most revolutionary art of the day. Within two years she was moving in the same circles as those responsible for this new work. Her commitment to the Abstract Expressionists, combined with her appreciation of past art, resulted in a new painting technique and works such as Small's Paradise [SAAM, 1967.121]. She spread huge pieces of canvas on the floor of her studio, pouring the acrylic paint from cans and pushing it with sponges. Frankenthaler thinned the paint so that the pigment did not sit on the surface of the canvas as paint always had, but soaked into the fabric, establishing a new relationship between the medium and its support. Frankenthaler's "stain painting" was her personal invention.

The existence of a distinct feminine aesthetic, an issue that has preoccupied many critics, is particularly relevant to Frankenthaler's expressively fluid work. Frankenthaler herself in 1965 questioned those who saw her work solely in terms of gender, calling this approach "superficial." Later in the same interview, however, she mused, "I wonder if my pictures are more lyrical (that loaded word!) because I'm a woman?"

Elizabeth Chew Women Artists (brochure, Washington, DC: National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution