Stanley, John Mix

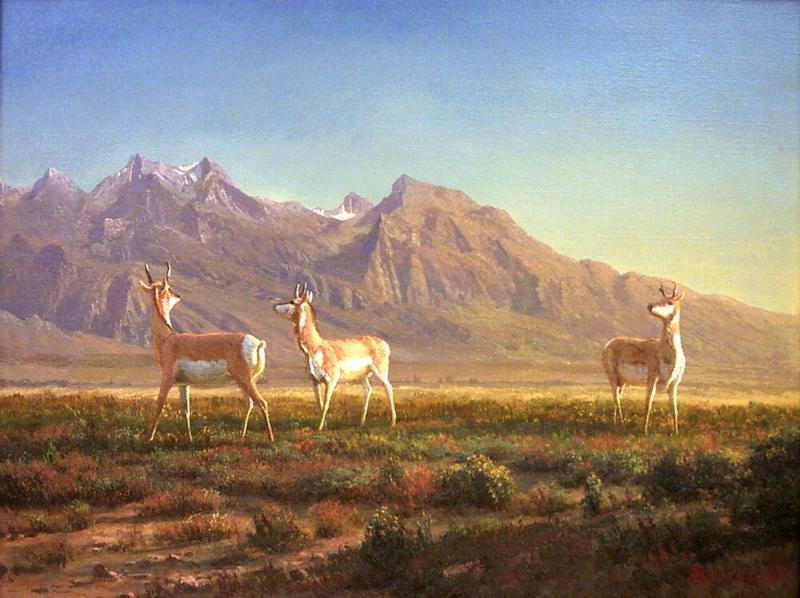

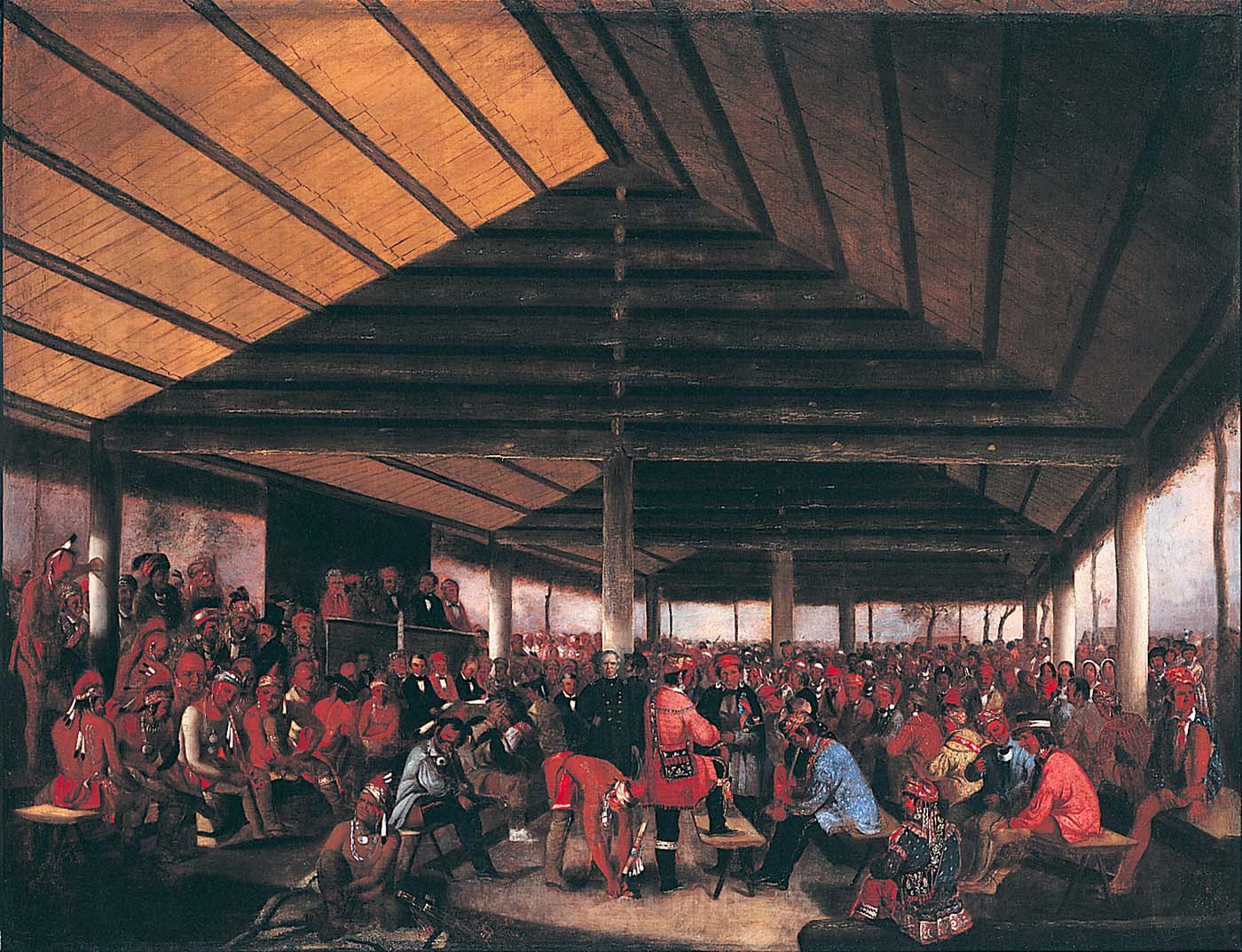

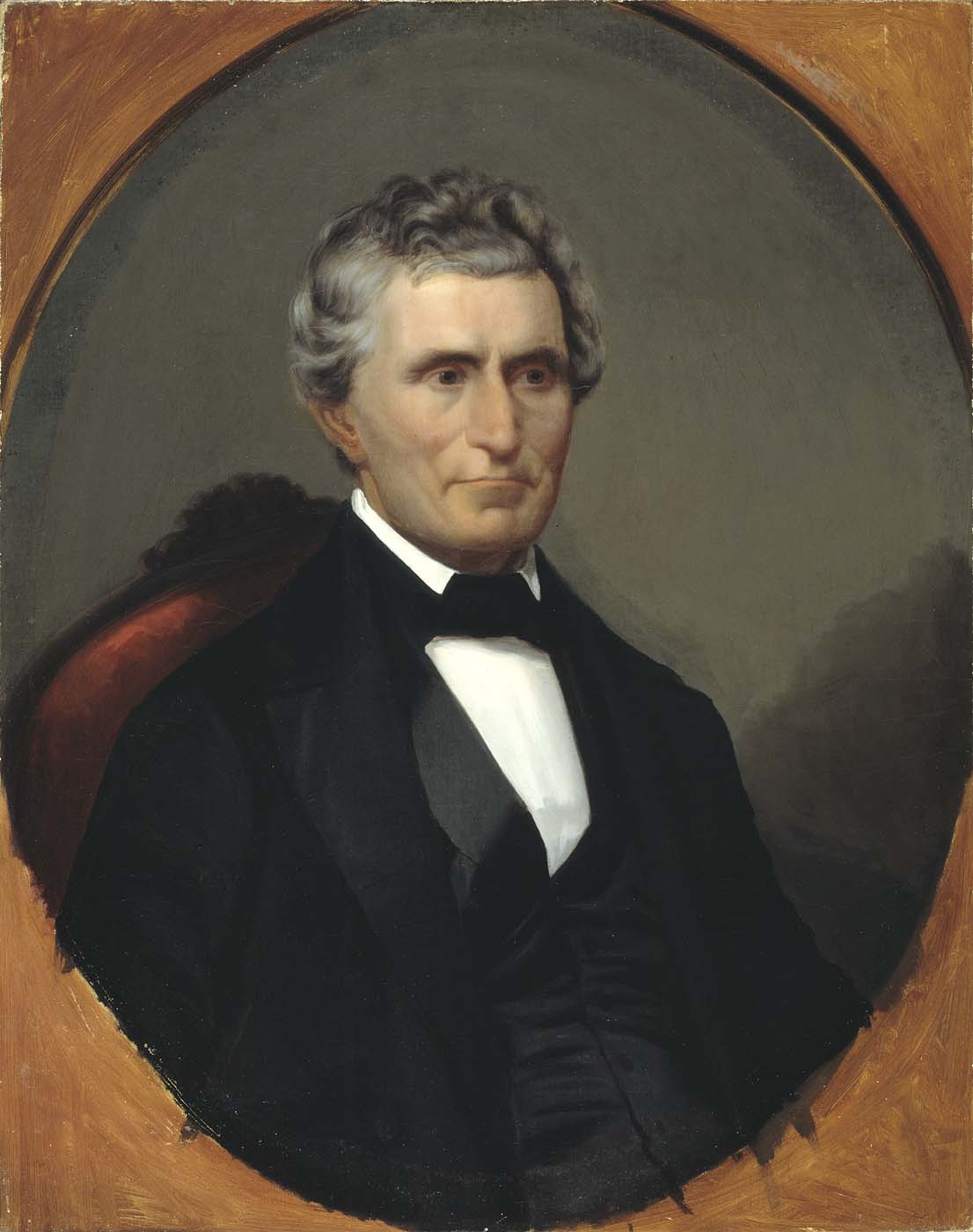

Born 1814, Canandaigua, N.Y. 1828, orphaned; apprenticed to a coachmaker. 1834, moved to Detroit as house and sign painter. 1835, studied with James Bowman, a portraitist trained in Italy. 1836–38, painted portraits around Chicago. 1839, Fort Snelling, Minn., began to concentrate on Indian portraits and scenes. Returned East; saved enough painting portraits and taking daguerreotypes to enable him to go West again in 1842. Set up studio, Fort Gibson, Oklahoma Territory; painted frontiersmen and Indians. Lived in Indian country until 1845, painting grand Indian council at Tallequah (1843) and a second council of prairie Indians. 1846, became artist with Kearny military expedition to California. 1847, painted Indian portraits in Oregon Territory; 1848–49, Polynesian portraits in Hawaii.

1850–51, displayed his Indian Gallery in cities in the East. 1851, displayed 150 paintings in Smithsonian (catalogue, 1852); offered to U.S. government for $19,200 plus $12,000 in expenses. 1853, official artist for Stevens expedition, northern railway survey, from St. Paul, Minn., to Puget Sound, Wash. Used field sketches to paint enormous panorama containing forty-two scenes of western life (now lost).

Married, 1854. Congress refused to purchase Indian Gallery; collection largely destroyed by fire, 1865. Fire at P.T. Barnum's American Museum, New York, destroyed more of his Indian paintings. Died 1872, Detroit, Mich.

Although many works in Stanley's large oeuvre of Indian paintings were destroyed by fire, many more survive than is generally thought. The five in the NMAA constitute a significant group. Although he traveled as widely as George Catlin in quest of his subject, Stanley differs from Catlin in that he made his initial records of Indian life with camera and pencil and postponed execution of his paintings until after his expeditions. He also organized his canvases in a self-conscious, academic manner; and lacking Catlin's empathy with the Indians and their cultures, he viewed them as an outsider, with no little condescension. In one sense, his paintings are valuable precisely as documentation of that widely shared attitude.

William Kloss Treasures from the National Museum of American Art (Washington, D.C. and London: National Museum of American Art with the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985