Thomas Cole

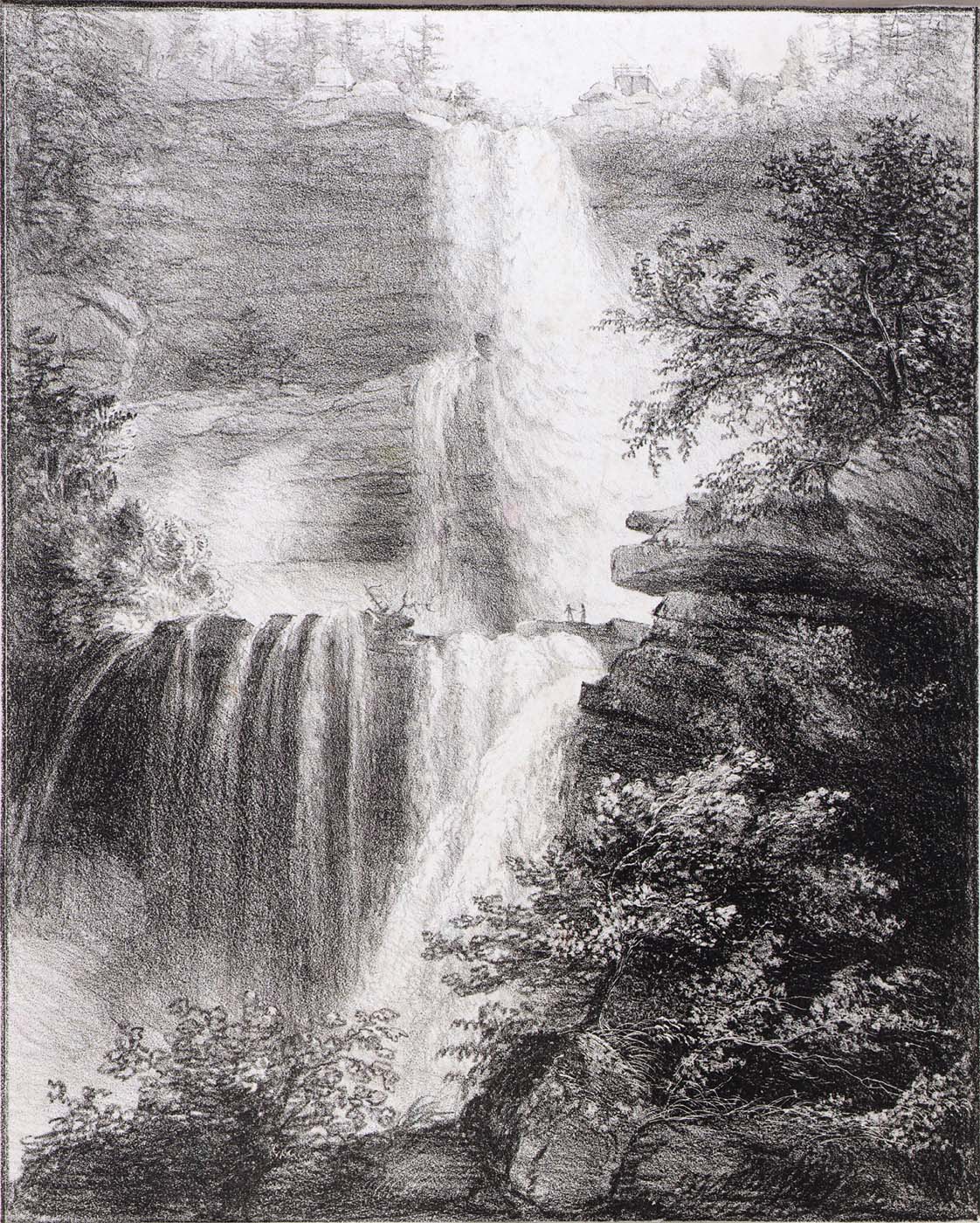

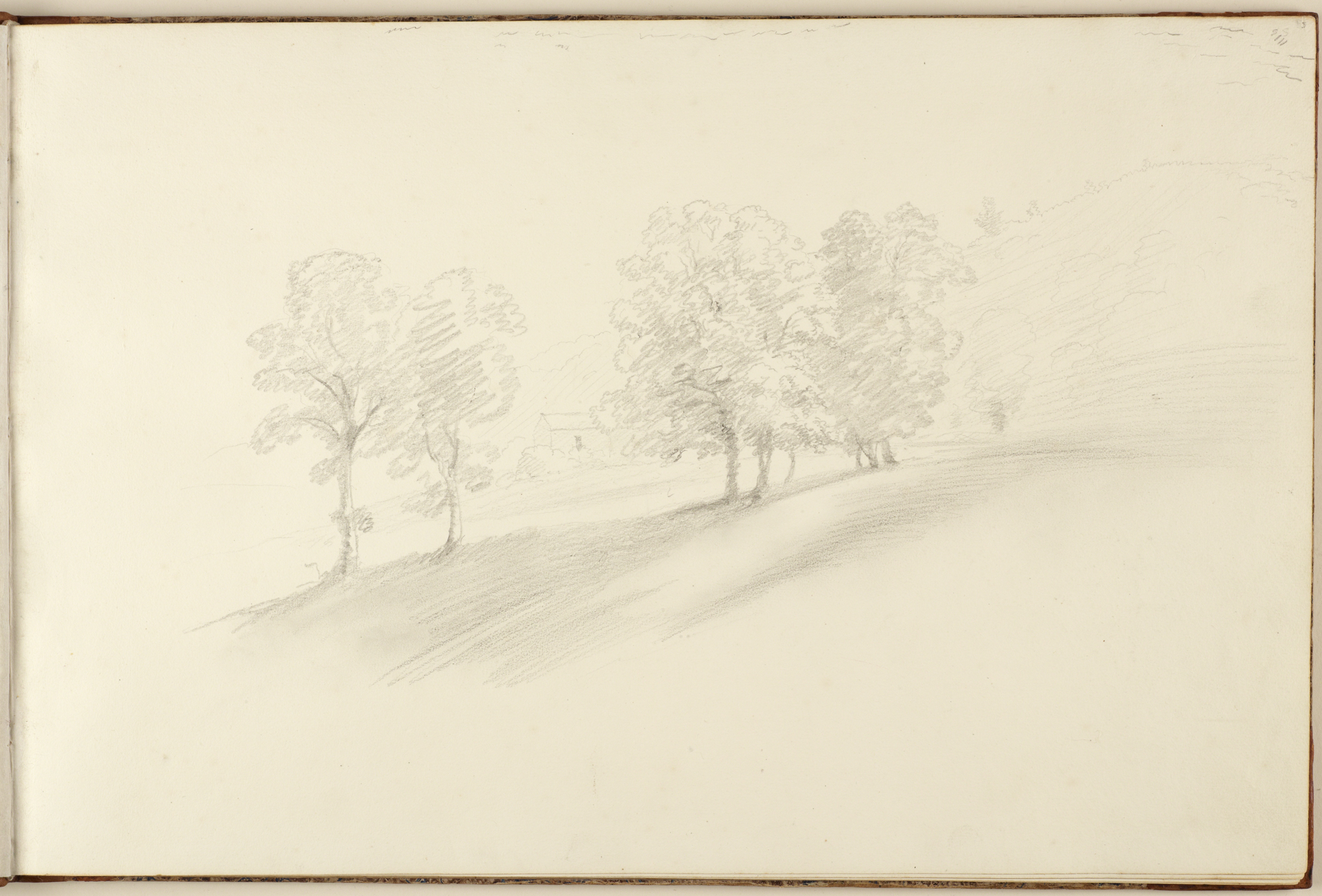

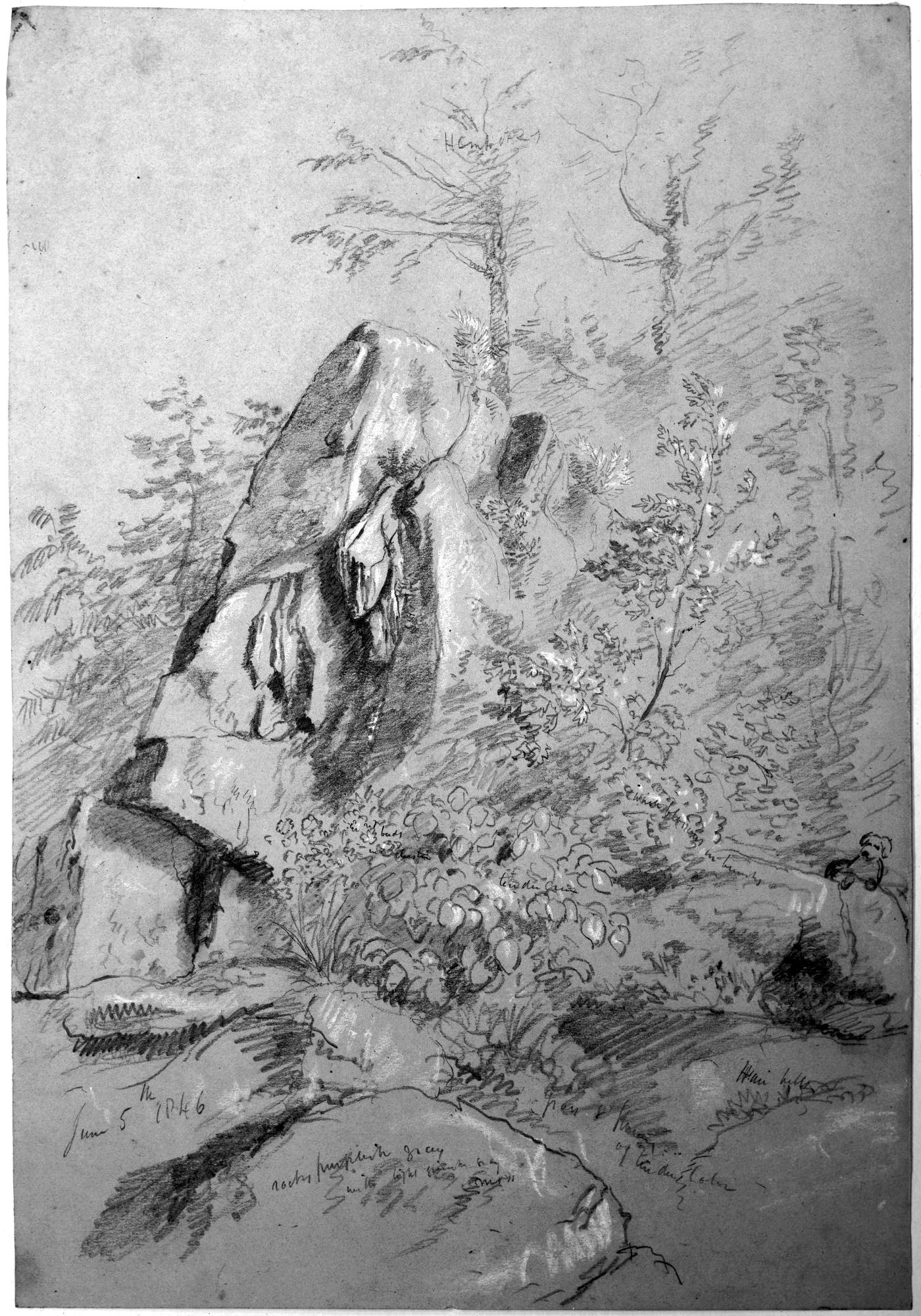

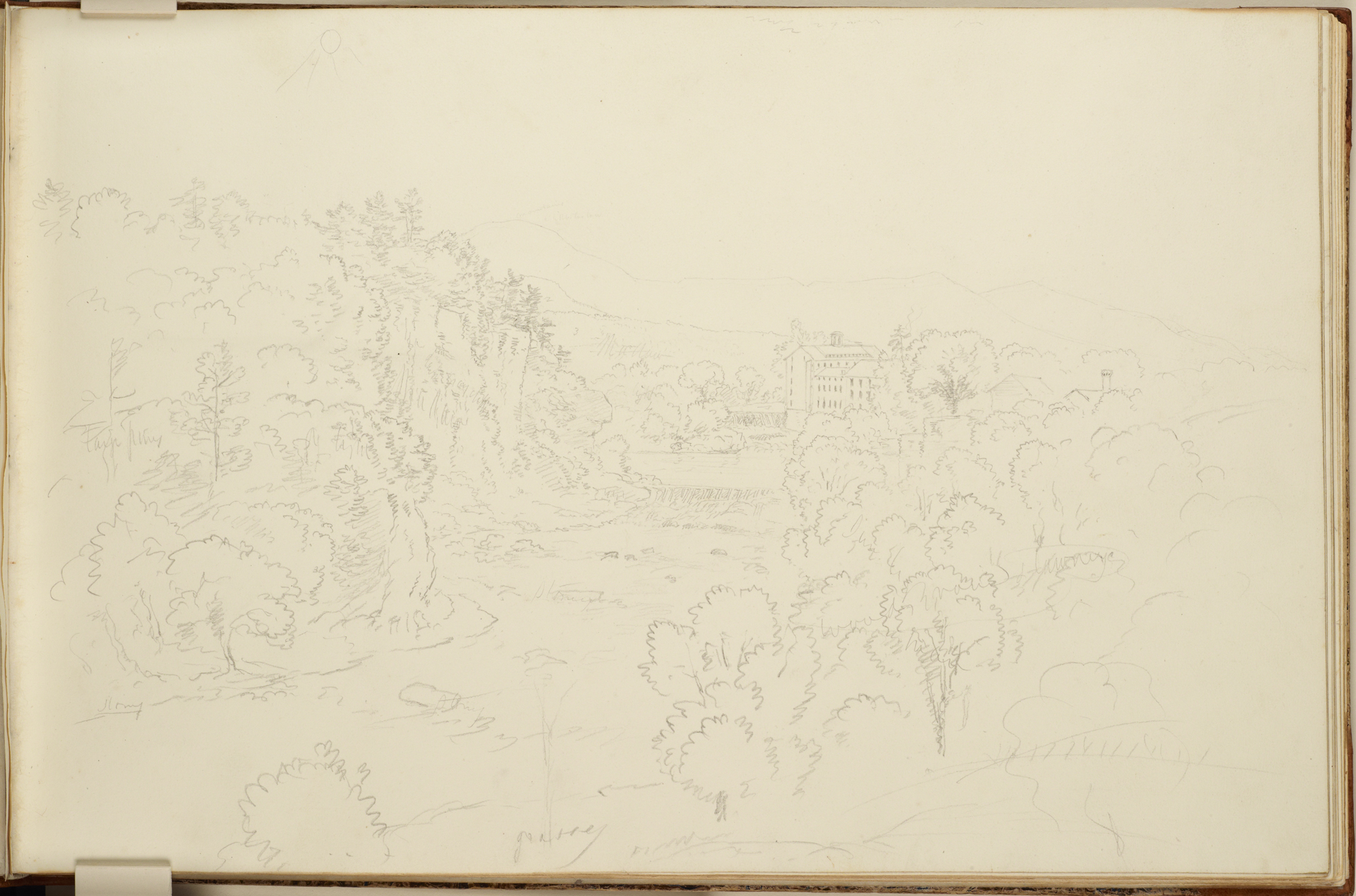

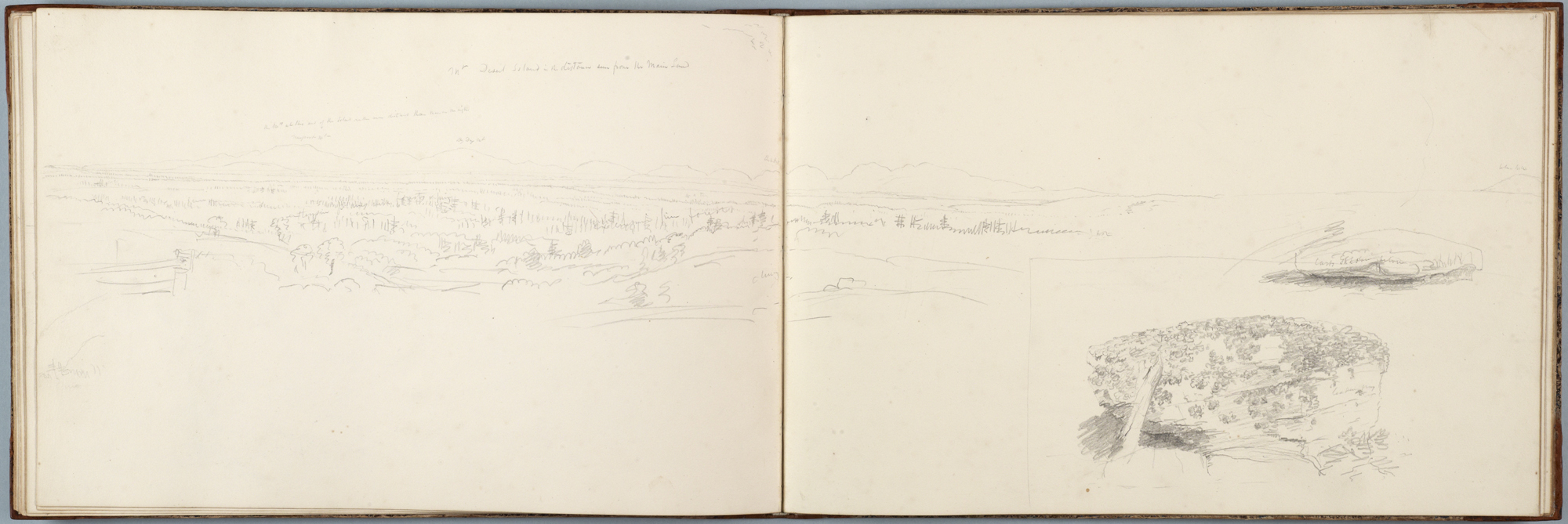

Thomas Cole was the first of the Hudson River School of painters, often characterized as being the first native American school of painting. Though devoted to the study of nature, and usually thought of as a landscape artist, moralistic and religious themes were central to Cole's paintings.

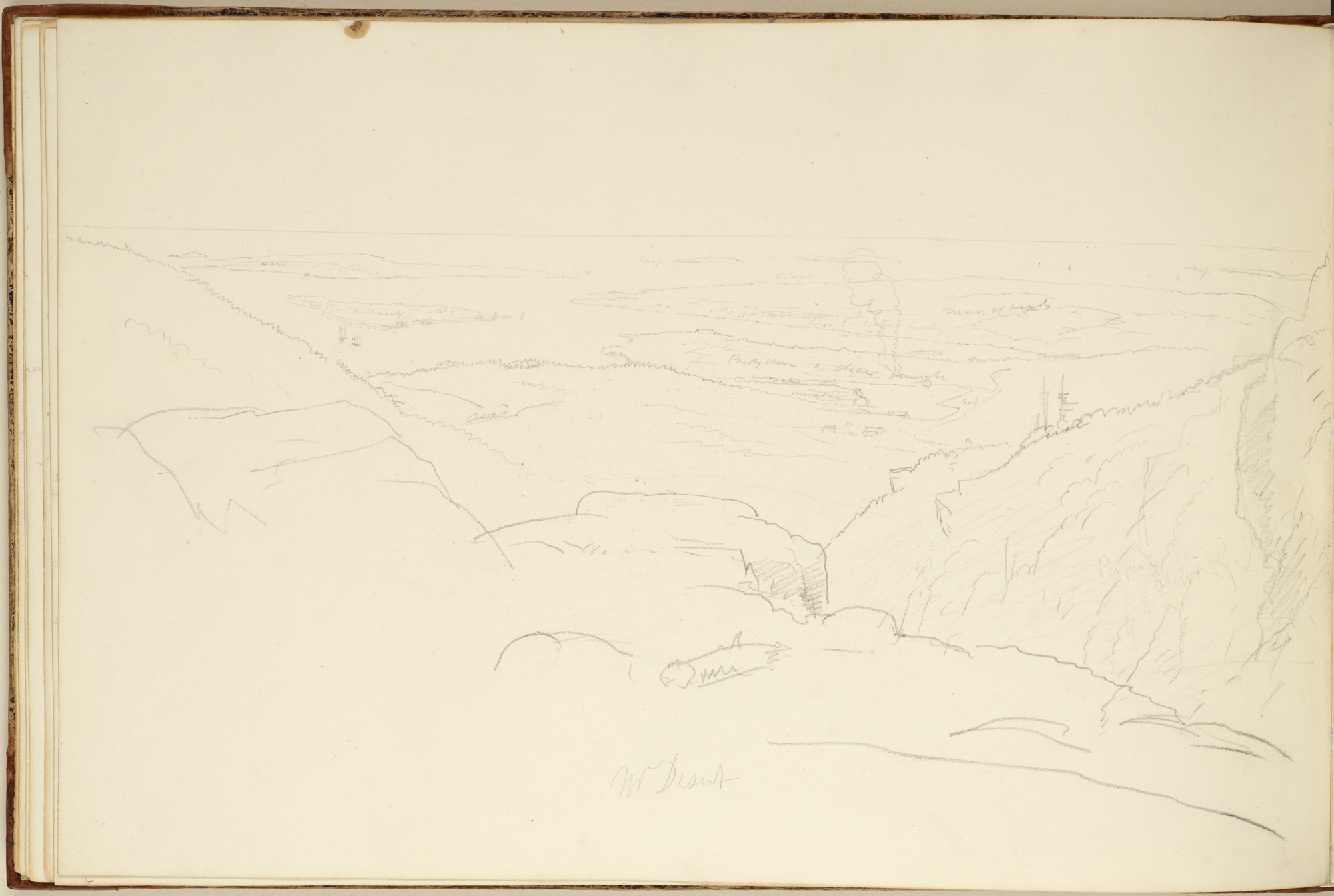

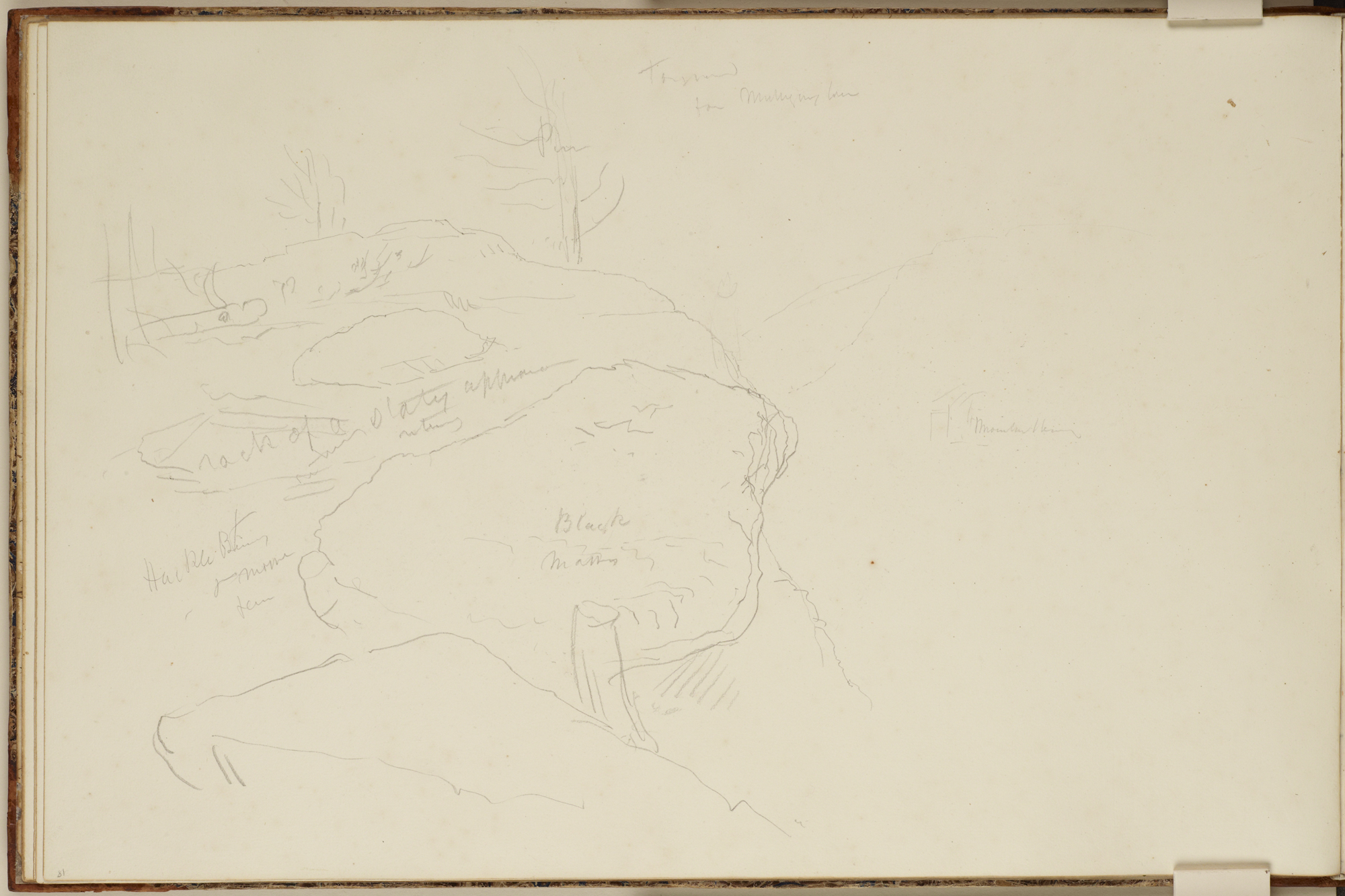

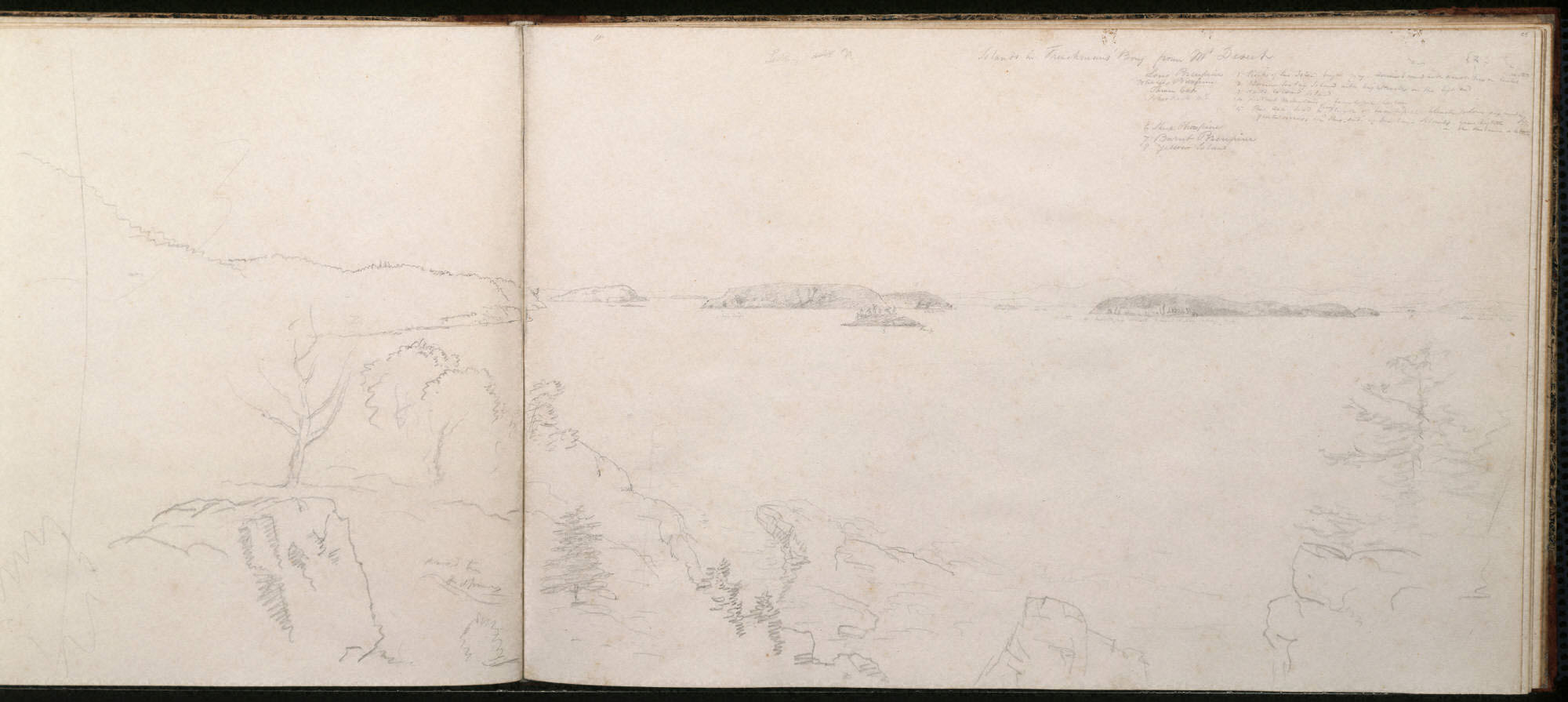

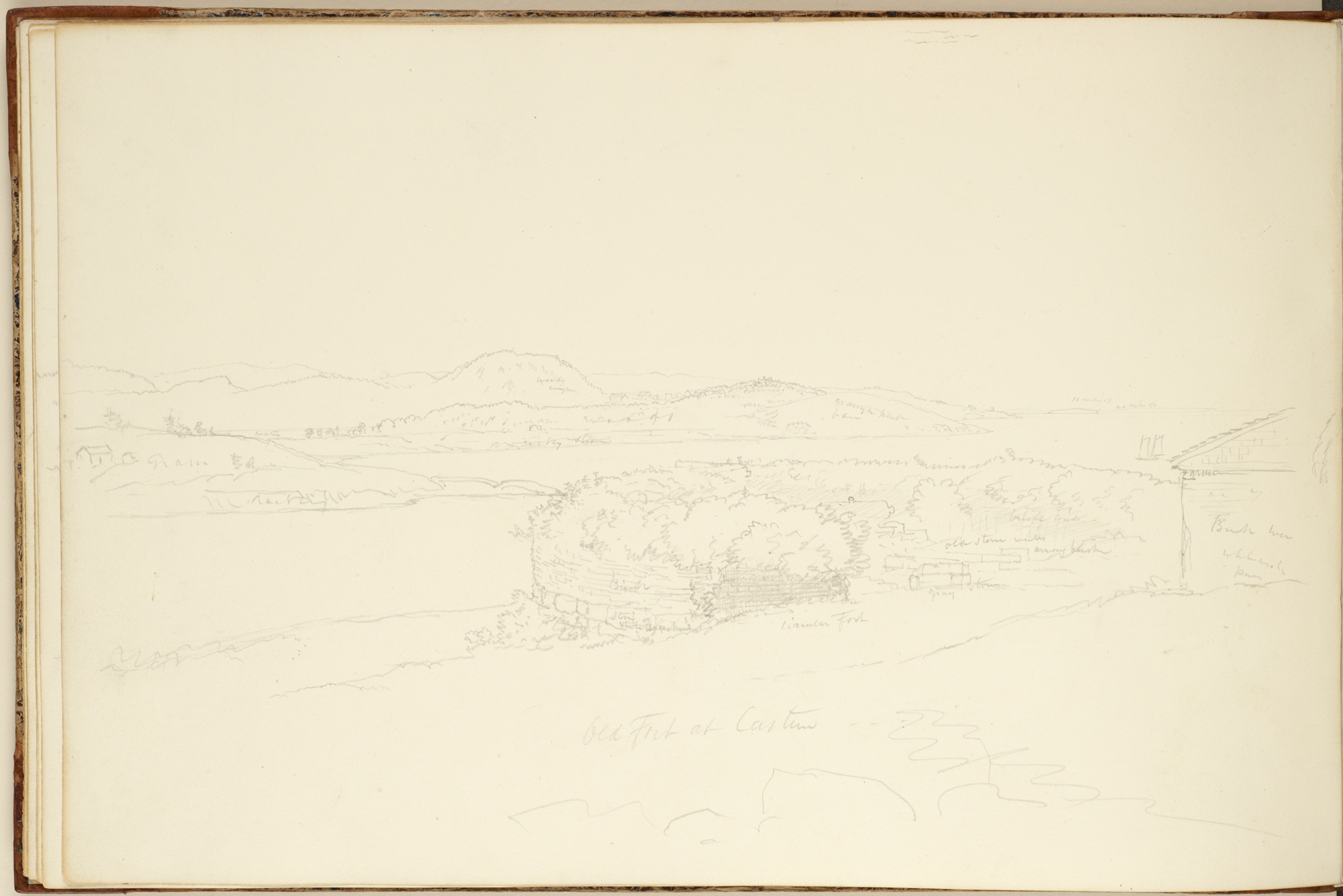

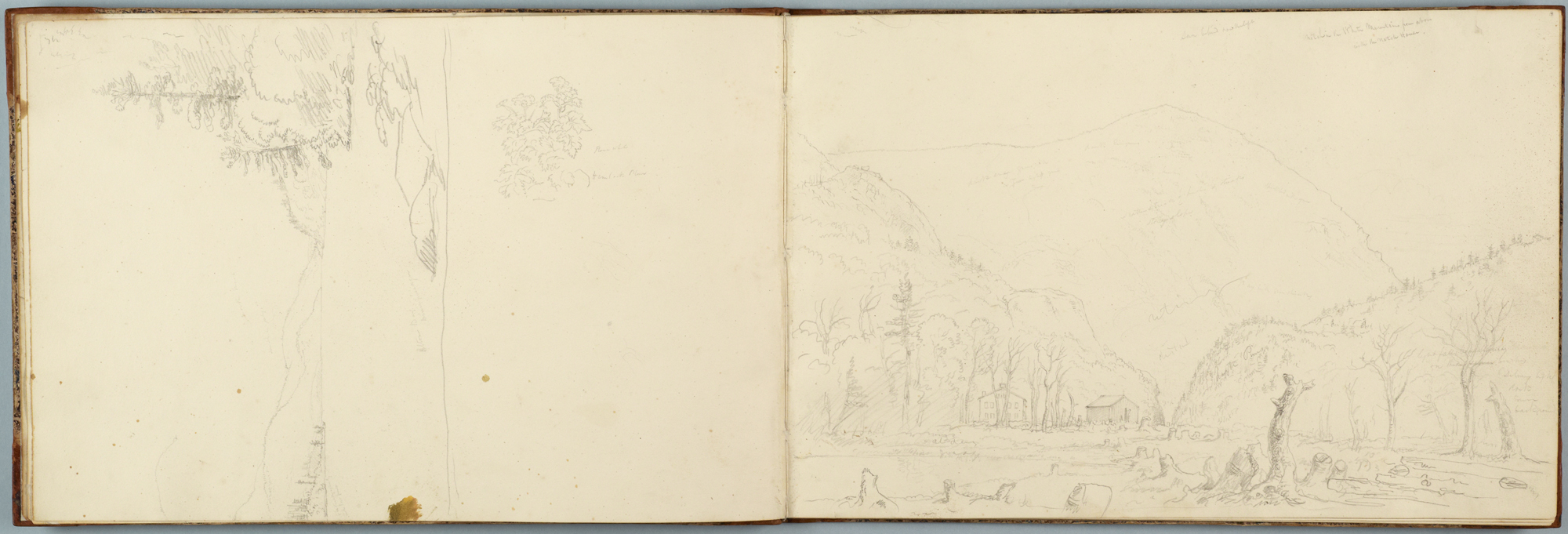

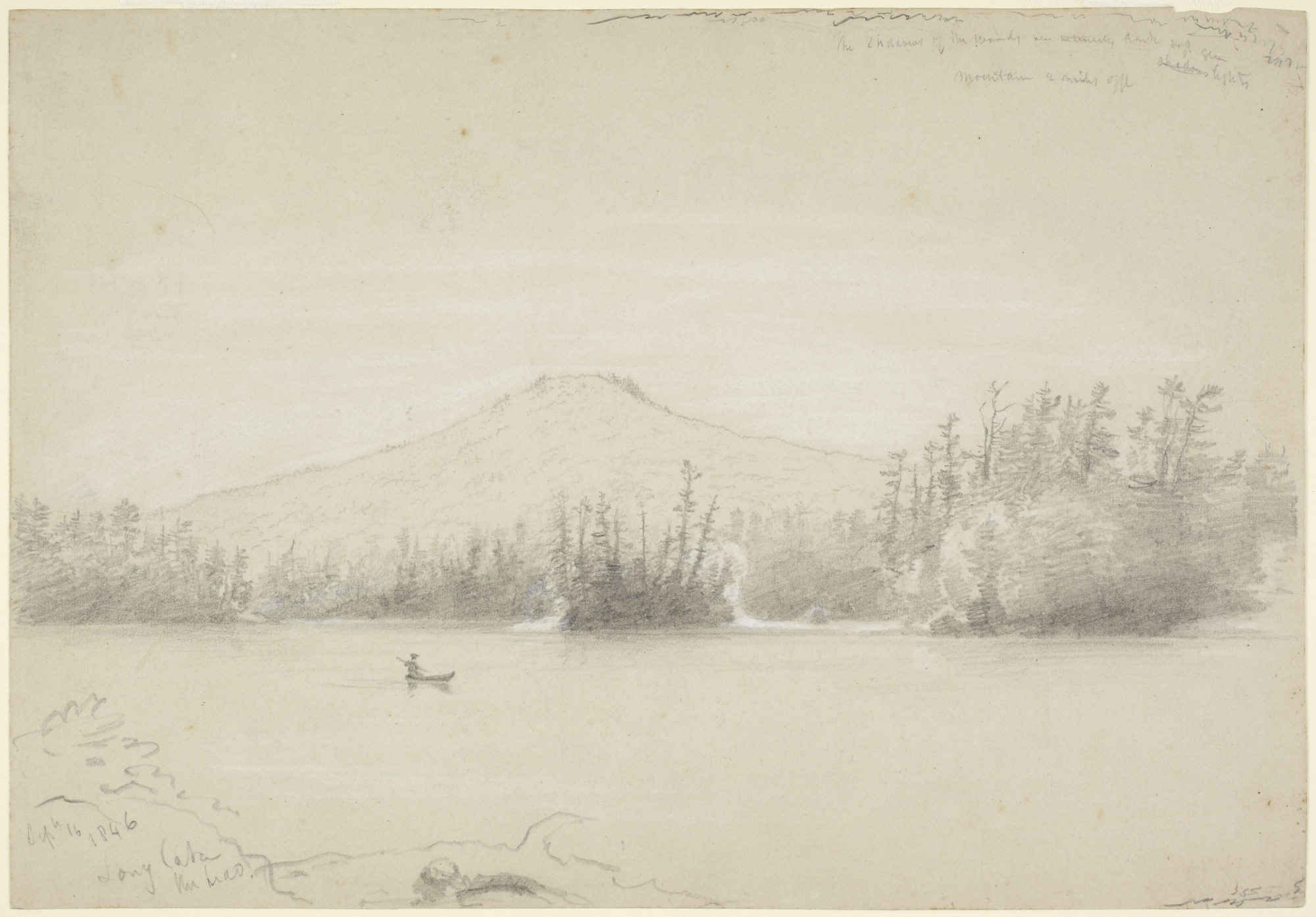

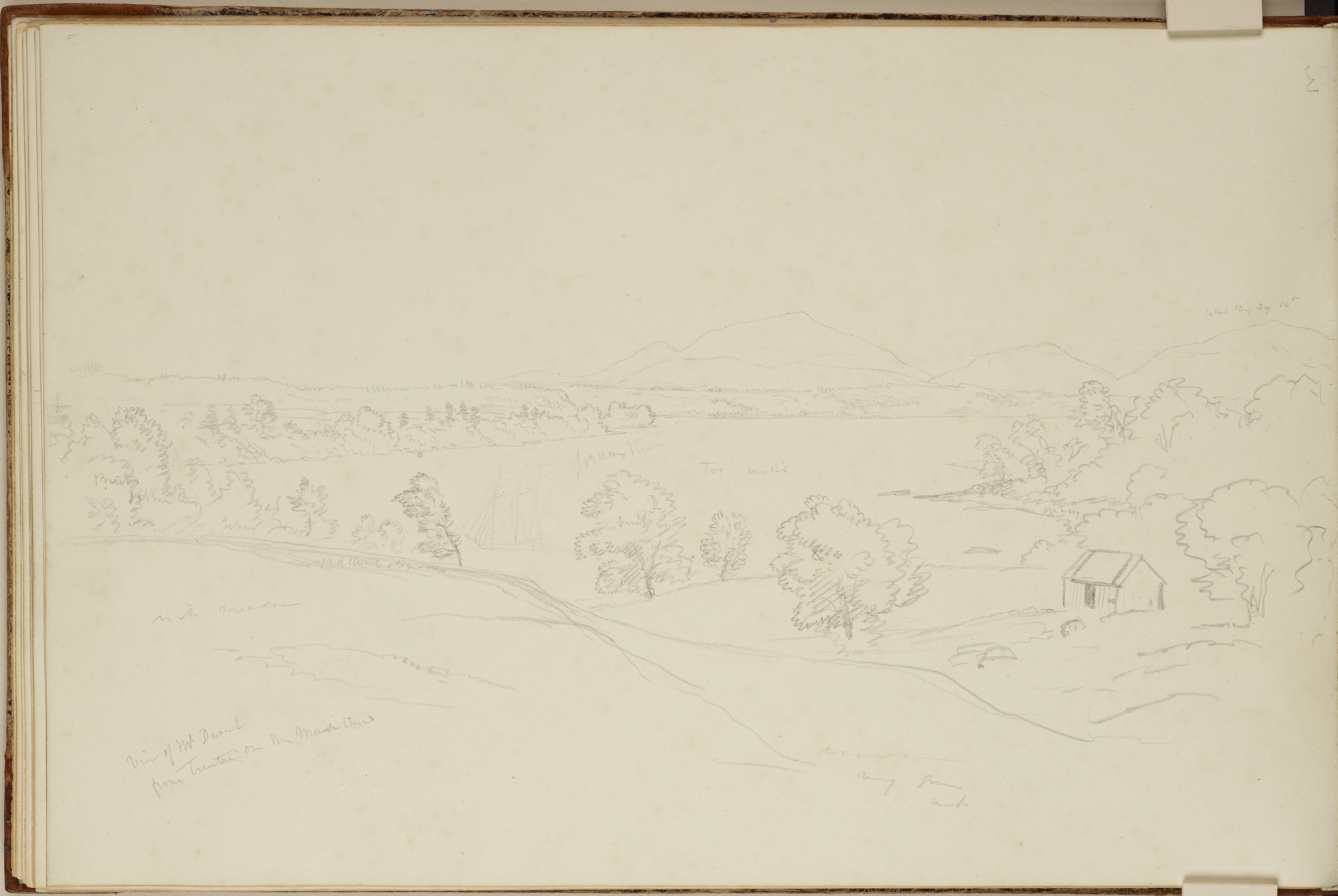

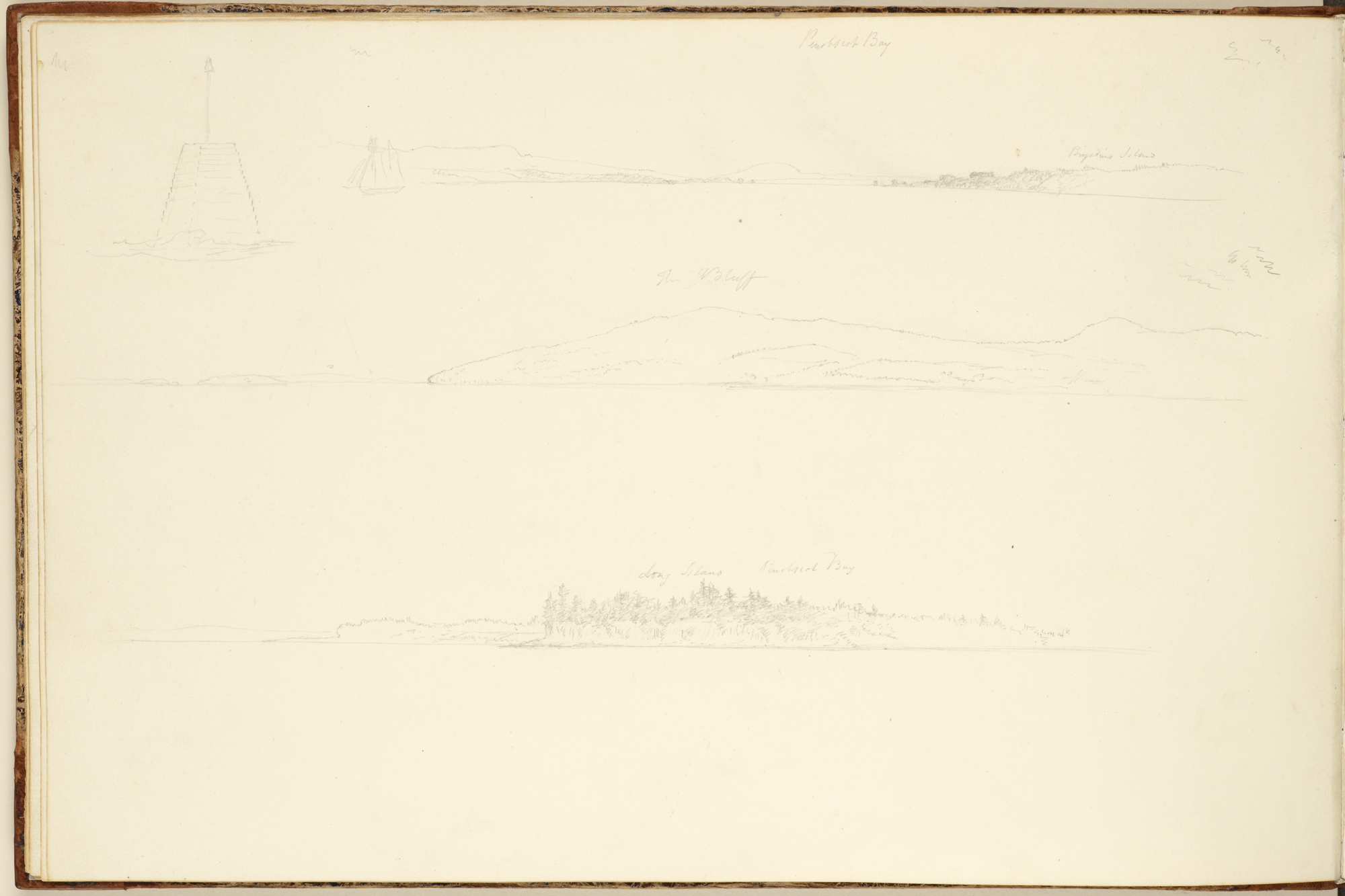

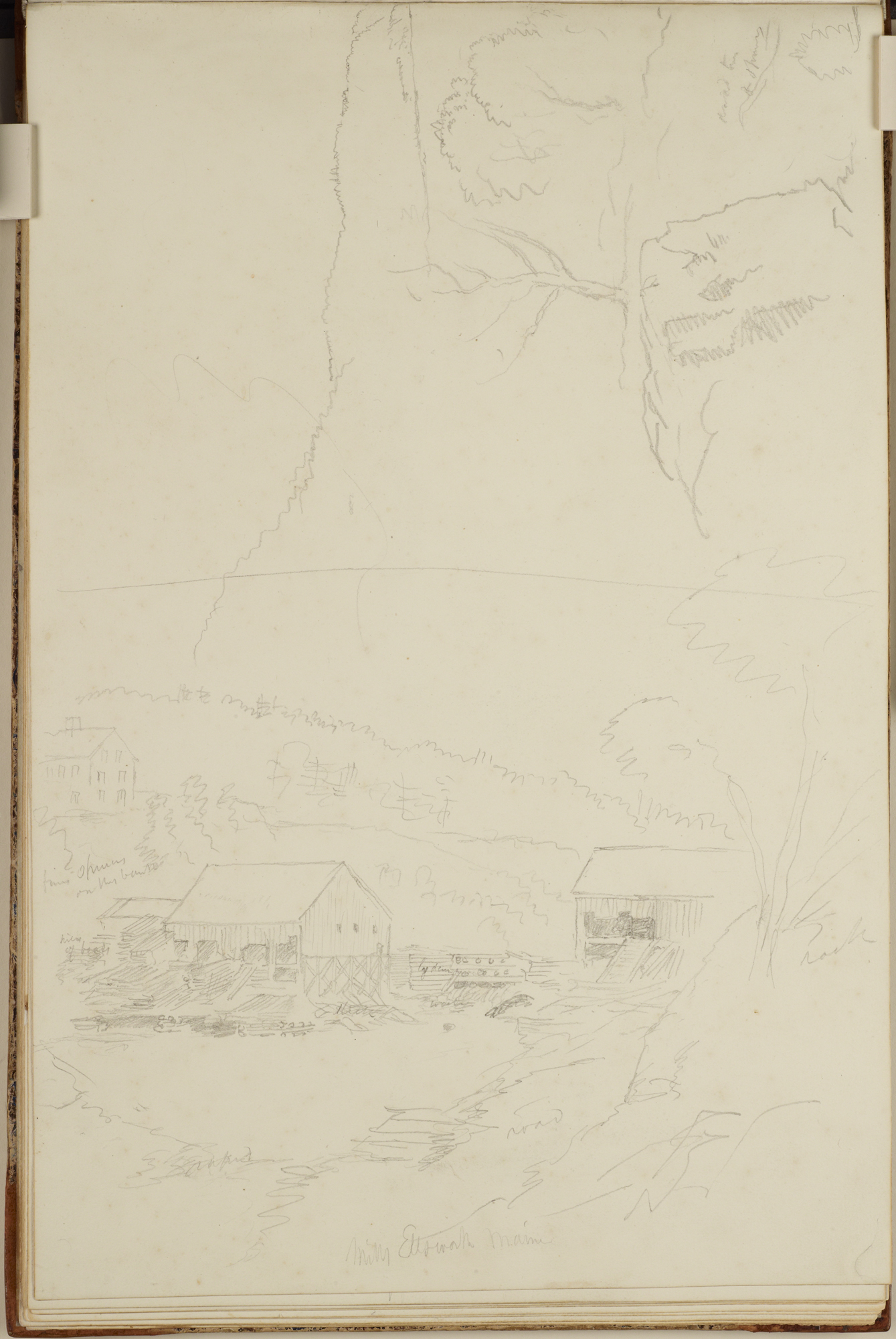

Cole was born in Lancashire, England, and at the age of seventeen, he arrived with his family in Philadelphia. He worked as a commercial engraver at first, but by about 1823–1824 he had determined to become an artist. In 1825 he sold three landscape paintings and that summer he took his first sketching trip up the Hudson River. In 1826 he was elected to the National Academy of Design.

In 1829 he went to England and exhibited there, then to France, and in 1831–1832 he lived and toured in Italy. In Rome he occupied the studio of Claude Lorrain, the famous seventeenth-century French artist, whom Cole considered "the greatest of all landscape painters." In 1836 he returned to America and married Maria Bartow of Catskill, where he then set up his studio and residence. In 1841–1842 he made a second trip abroad to London, Paris, Rome, and Sicily. In 1842 he joined the Anglican Church. His first pupil, in 1844, was the landscape artist, Frederic E. Church.

Like [Washington] Allston and [Albert Pinkham] Ryder, Cole wrote poetry. He also kept a journal and wrote lengthy letters to his wife, friends, and patrons. Thus an intimate record of the viewpoint and activities of this gentle, pious, articulate, and reflective man is available through Louis Noble's books. A journal entry for May 31,1835, reads, in part:

"I did not go to church today. … I read a little, wrote, and walked, and looked at the landscape. … The south wind blew strongly, and dark masses of cloud moved across the twilight sky, the heralds of approaching storm. A leaden hue overspread the vale, the woods, and the distant mountains. How contagious is gloom! A flow of melancholy thoughts and feelings overwhelmed me for a time. I thought of the uncertainty of life; its bootless toil and brevity. The south wind, I thought, would still continue to blow, and bring up its dark clouds for ages after my works, and all the reputation I might gain had faded away, and become as though they had never been— swept by the wing of time into oblivion's gulf. And shall it be? Shall the spirit, that mysterious principle, unknown even to itself, that vivifies this earth, and generates these thoughts, sink also into the gloomy gulf of nonexistence, nor feel again created Beauty, nor see the Nature that it loved so much? It cannot be. The Great Originator, the Mighty One, the Unspeakable, hath not created for purposes vain and useless this power of conceiving … this wish and 'longing after immortality,' this hope … this faith which gives an energy to virtue, and raises in the breast these lofty aspirations … this fear of sinning, of deception and delusion. No! There are no fallacies with God. To prove that, if not to disprove all existence, would be to render all things doubtful."

Jane Dillenberger and Joshua C. Taylor The Hand and the Spirit: Religious Art in America 1700–1900 (Berkeley, Cal.: University Art Museum, 1972)

Objects at The Walters Art Museum (1)

Objects at The Amon Carter (2)

Objects at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art (3)

Objects at Archives of American Art (4)