James Rosenquist

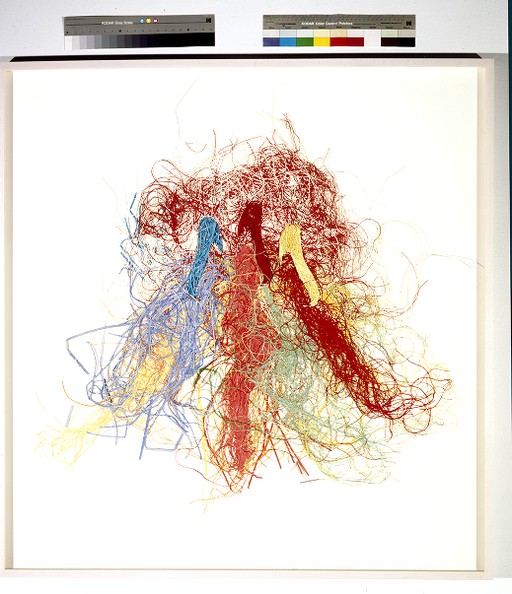

James Rosenquist studied at the University of Minnesota and in 1955 received a bursary from the Art Students League of New York. With Lichtenstein and Oldenburg, James Rosenquist is one of the masters of American Pop Art, a movement inspired by the consumer society, reacting against the aestheticism of Abstract Expressionism and using techniques taken from the worlds of the press, cinema and advertising. Rosenquist's work is situated after the movement's neo-Dada forerunners, Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Chamberlain and Stankiewicz, with the first representatives of the second wave of Pop Art, who came together in 1962 and would launch the vogue for this second American postwar style. Like other future exponents of Pop Art, he worked for a long time as a commercial artist, using his professional techniques in his later work. He also retained the visual associations of advertising with erotic connotations and a highly personal color sense. One of the bases of Pop Art is the observation that the great myths of the modern world, can now be found in the temples of the consumer society, the comic strips of the popular daily press, advertising hoardings, the heroes of cinema and so on. For Rosenquist, who retains in his personal work the impersonal techniques of mass-produced commercial imagery, the visual idea alone matters. Instead of using elements from advertising reproduced more or less unchanged, Rosenquist reworks them from photographs he takes himself. The scale of the objects or fragments of objects varies within a single painting, different points of view combine and while some elements are clear at once, others remain hard to identify and affect the viewer only through their juxtaposition. I Love You with my Ford of 1964 consists of three rectangular and contiguous strips showing a car radiator, the face of a woman whose neck is being kissed and a close-up of spaghetti in tomato sauce. By excessively enlarging everyday objects, he forces us to see them out of context. Unlike other Pop artists, Rosenquist does not isolate a single object in order to make it visible, but shows it in a way that is almost 'abstract'. The composition forces viewers to move in order to grasp the object; their eyes must adapt and avoid all that does not interest them directly. In reversing pictorial conventions in this way and disturbing the viewers' way of seeing, Rosenquist constantly obliges them to make choices. His collages, the size of poster advertisements, remain Pop Art's most enigmatic and provocative images. In addition to painting, Rosenquist also explores the possibilities of different media and works in the round. From 1966 he painted the same subjects, taken from advertising, on strips of transparent plastic which were then hung in the exhibition space, such as Sliced Bologna of 1968, enabling the viewer to pass through the painting and move in its space. Pop Art has been criticized for presenting a distorted and unfaithful representation of reality, but in fact the aims of artists like Rosenquist were closer to those of the American Post-Constructivists and Minimalists than to, for example, the New Realists. His color range is unusual in that all the shades are mixed with white, and his later works bring him closer to the abstraction of Noland and Kelly. Source: Benezit Dictionary of Art