Berenice Abbott

"Paris was where the 20th century was." Should the remark so often quoted and attributed to Gertrude Stein prove apocryphal, it would make no difference. At the turn of the century and again after World War I, it seemed that most of the artistic and literary ferment of the modern world was focused in that city. To Paris in the 1920s came Berenice Abbott, a young woman fresh from Ohio State University's School of Journalism and from New York's Greenwich Village. Yet, despite this experience, she was still looking for her career, for her real profession and life's work. Born in Ohio in 1898, she had spent unhappy early years as the child of divorced parents and, after attending Ohio State University, had left the Midwest (for good) in 1918 for New York city and the Village. Ostensibly she was seeking a career in journalism and had moved to New York intending to pursue that subject at Columbia University. In fact the move to New York only presaged another in 1921, this time to Paris to study sculpture. "You're finding yourself as you go along when you're young,"she has remarked. "Youth often enters a field that isn't always the right choice." (1)

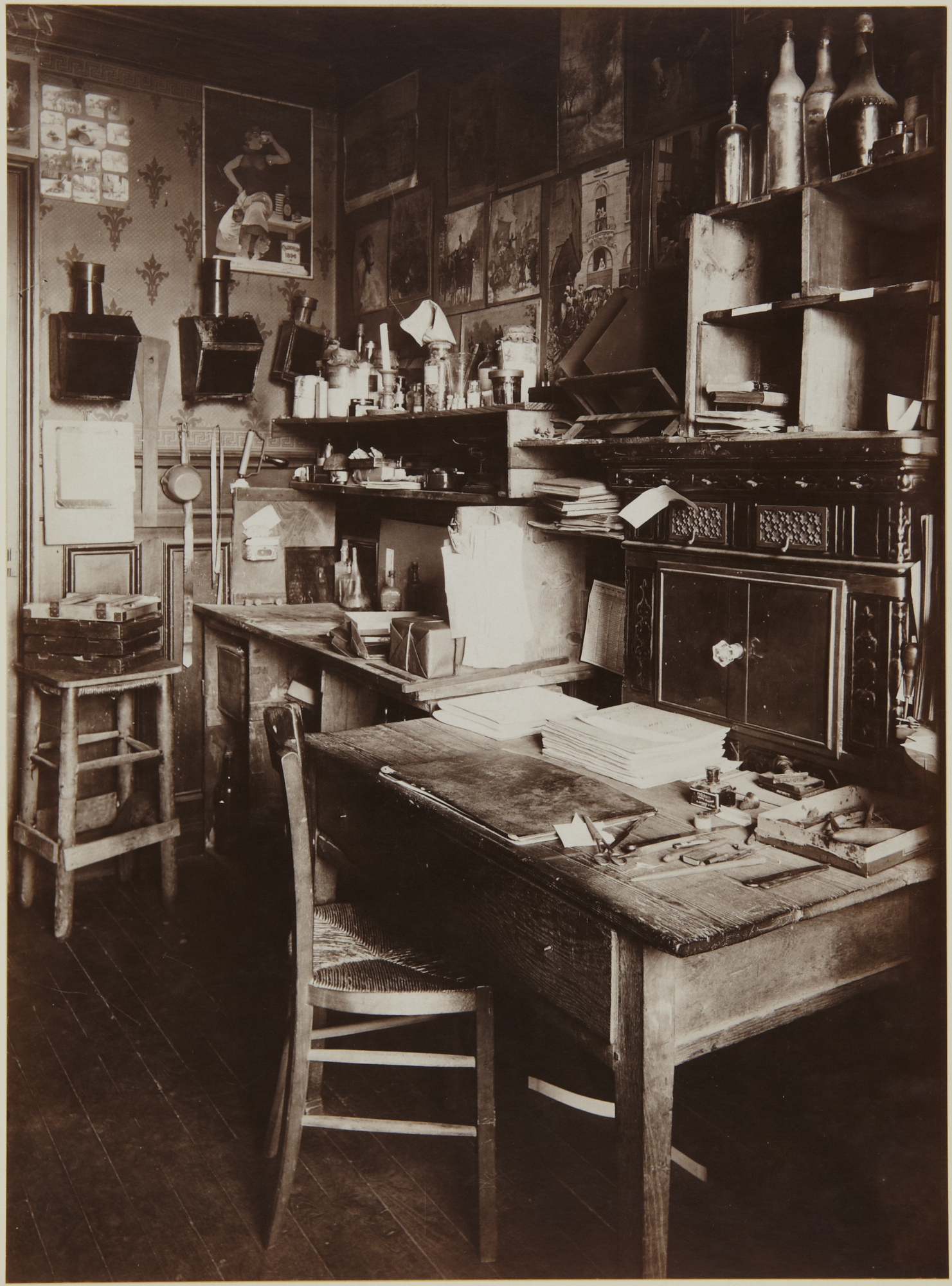

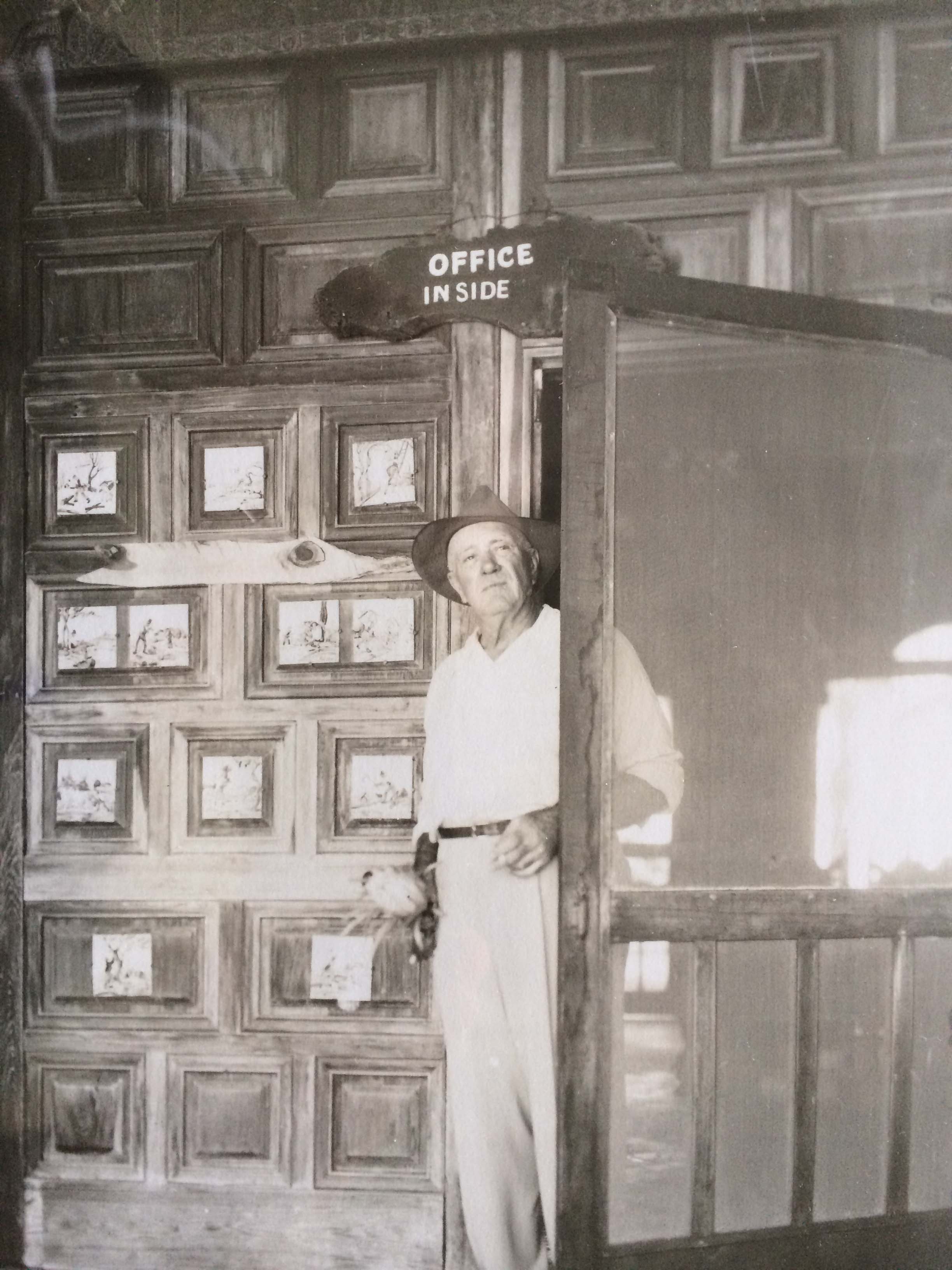

Her discovery of the right field came in 1923 and seems to have been entirely serendipitous. The famous photographer Man Ray needed an assistant, but insisted on one without previous knowledge of the craft. Young expatriates must eat, and Abbott applied. Her lack of knowledge qualified her for the job. Soon she was printing for Man Ray and discovering that she immensely enjoyed doing darkroom work. Later, at his suggestion, Abbott began to take her own first photographs. Both were surprised to discover how good she was. By 1925, with the aid of loans from Peggy Guggenheim and from Robert McAlmon (one of the "charmed circle" surrounding Gertrude Stein), she had set up her own studio on the Left Bank. There she pursued portrait photography which absorbed her at that time.

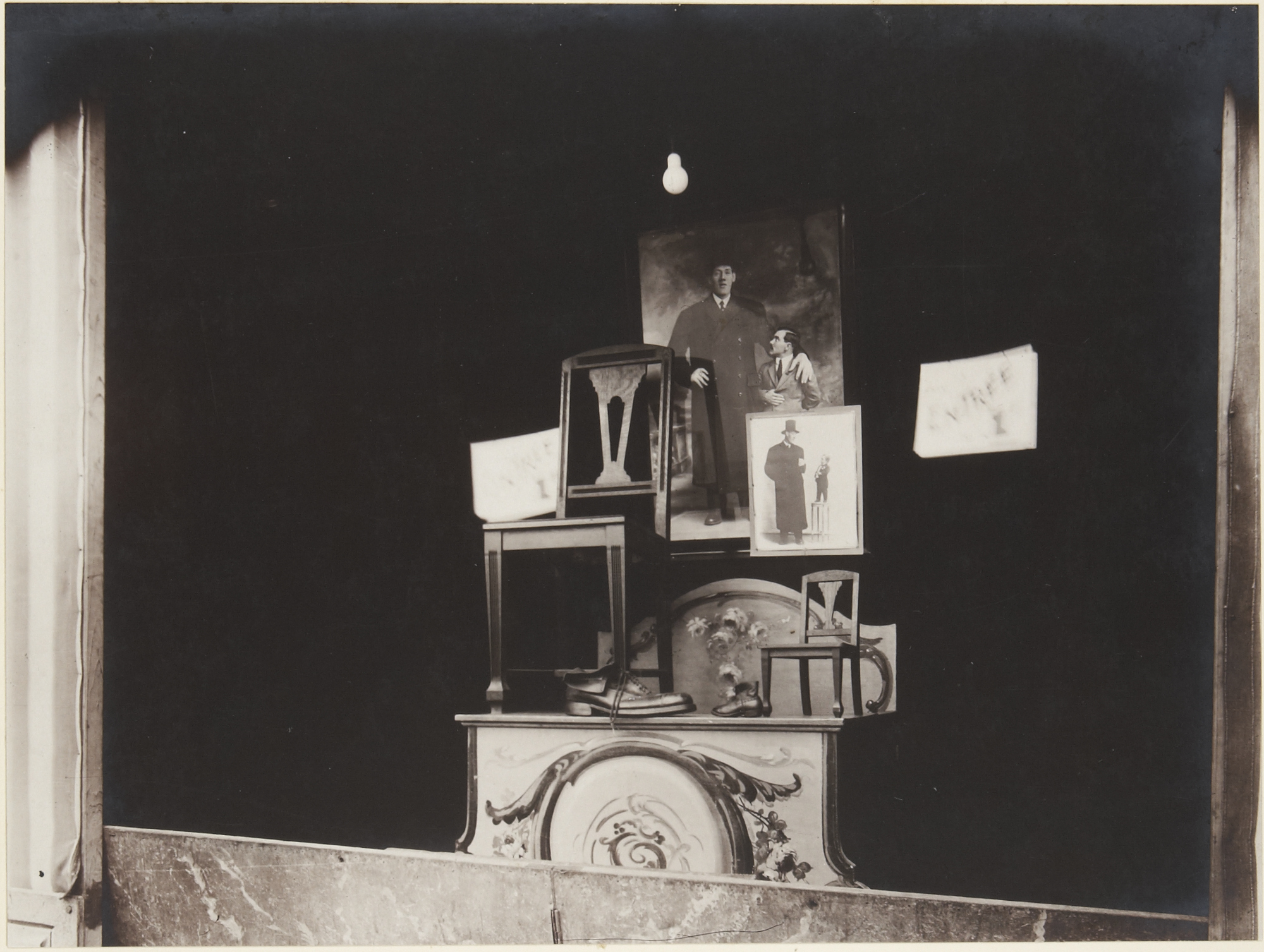

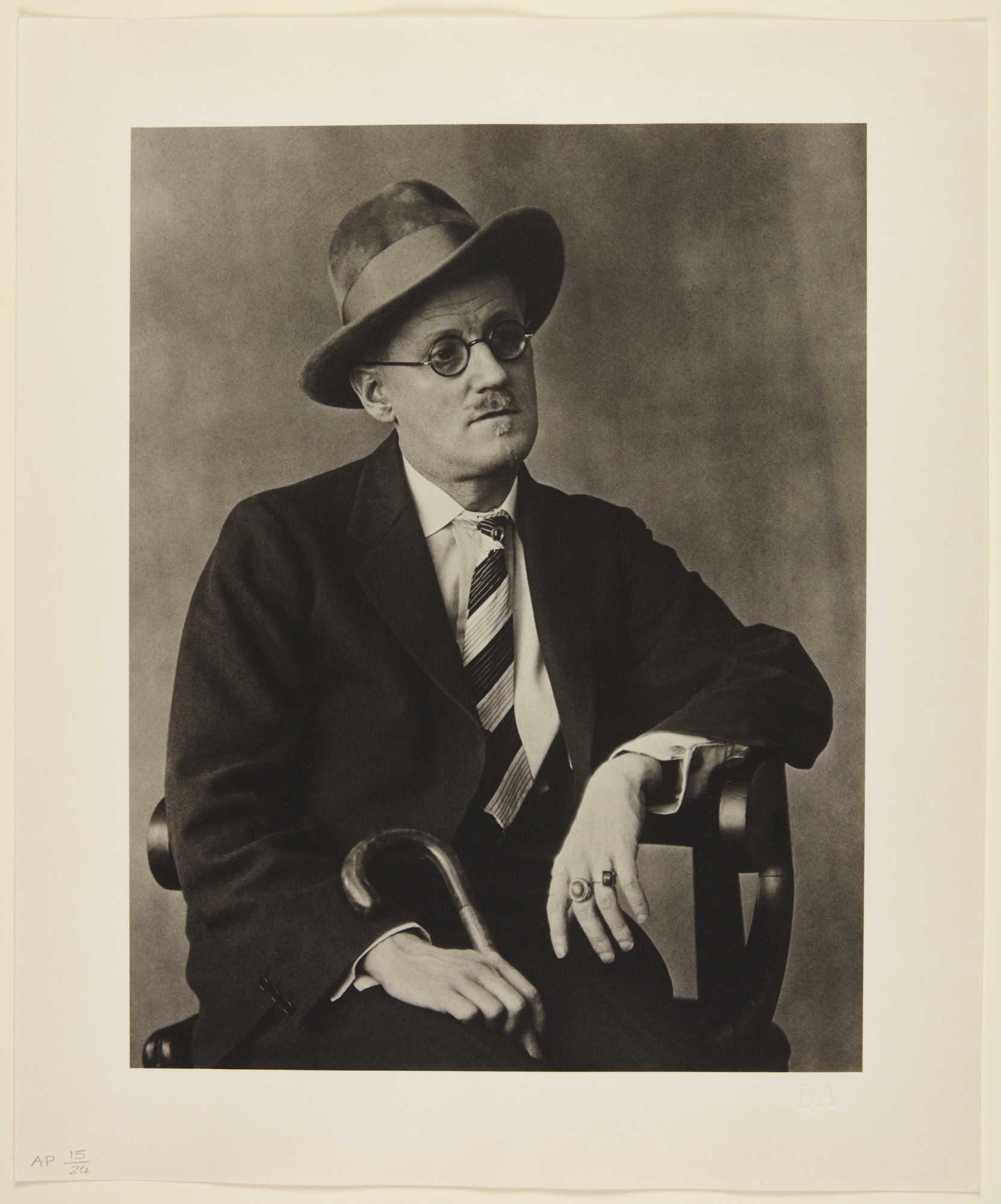

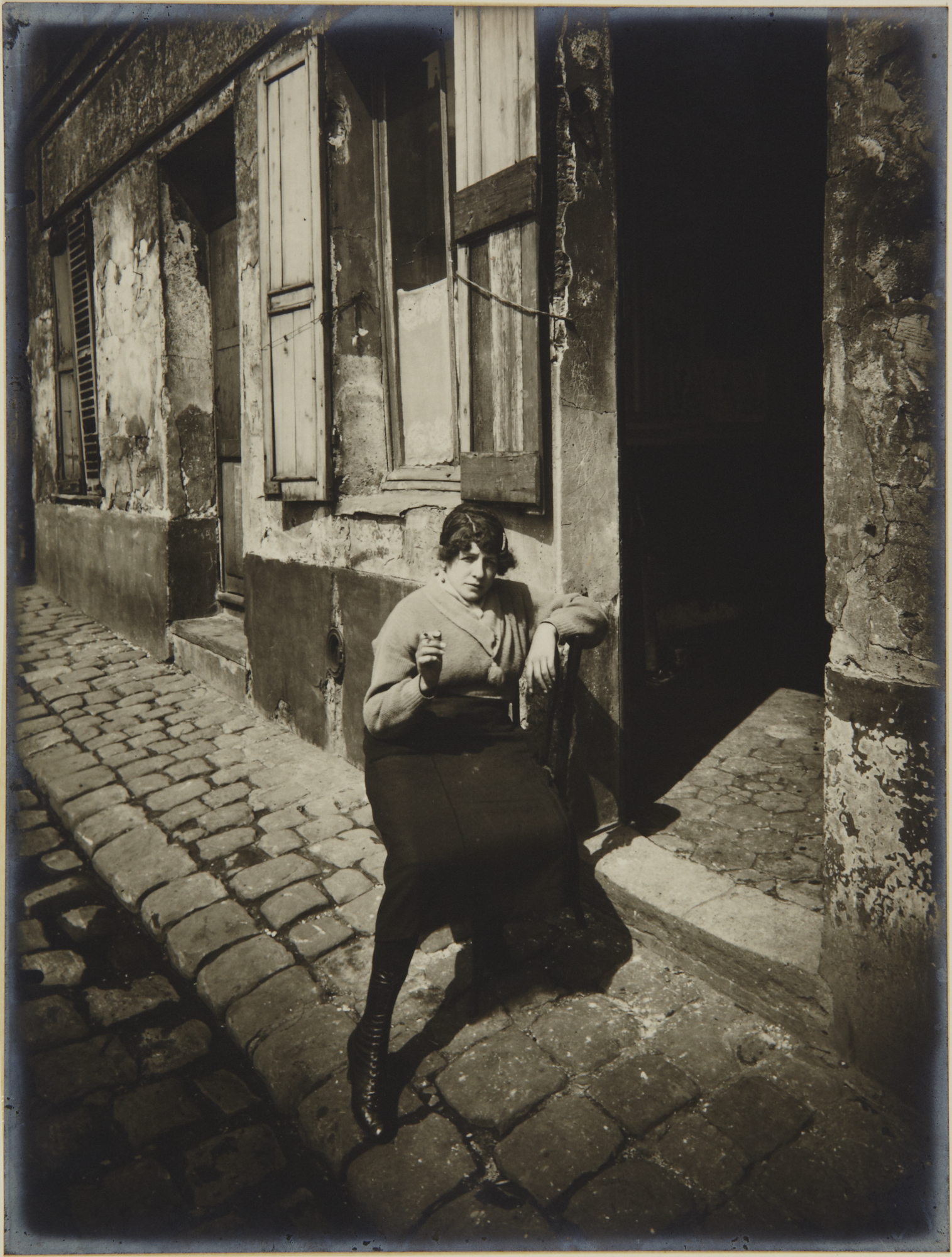

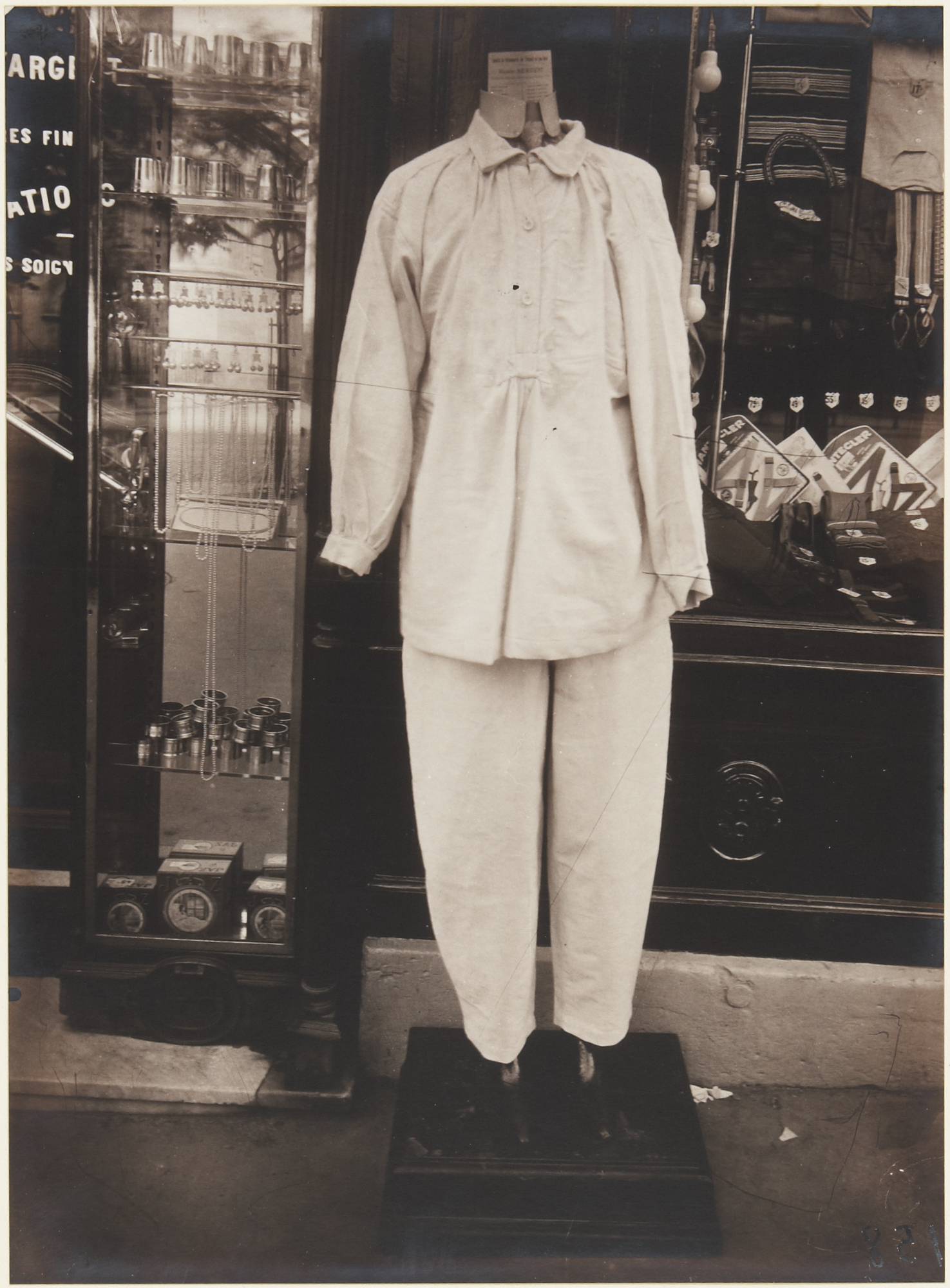

A selection of images of the stream of notables who found their way to Berenice Abbott's studio are presented in this exhibition. Figures from the world of fashion and the haut monde of Parisian society mix freely with some of the era's legendary literary figures and artists, including the dadaists and surrealists out pour épater le bourgeois. Abbott presents them all with what one can only term an imaginative realism.

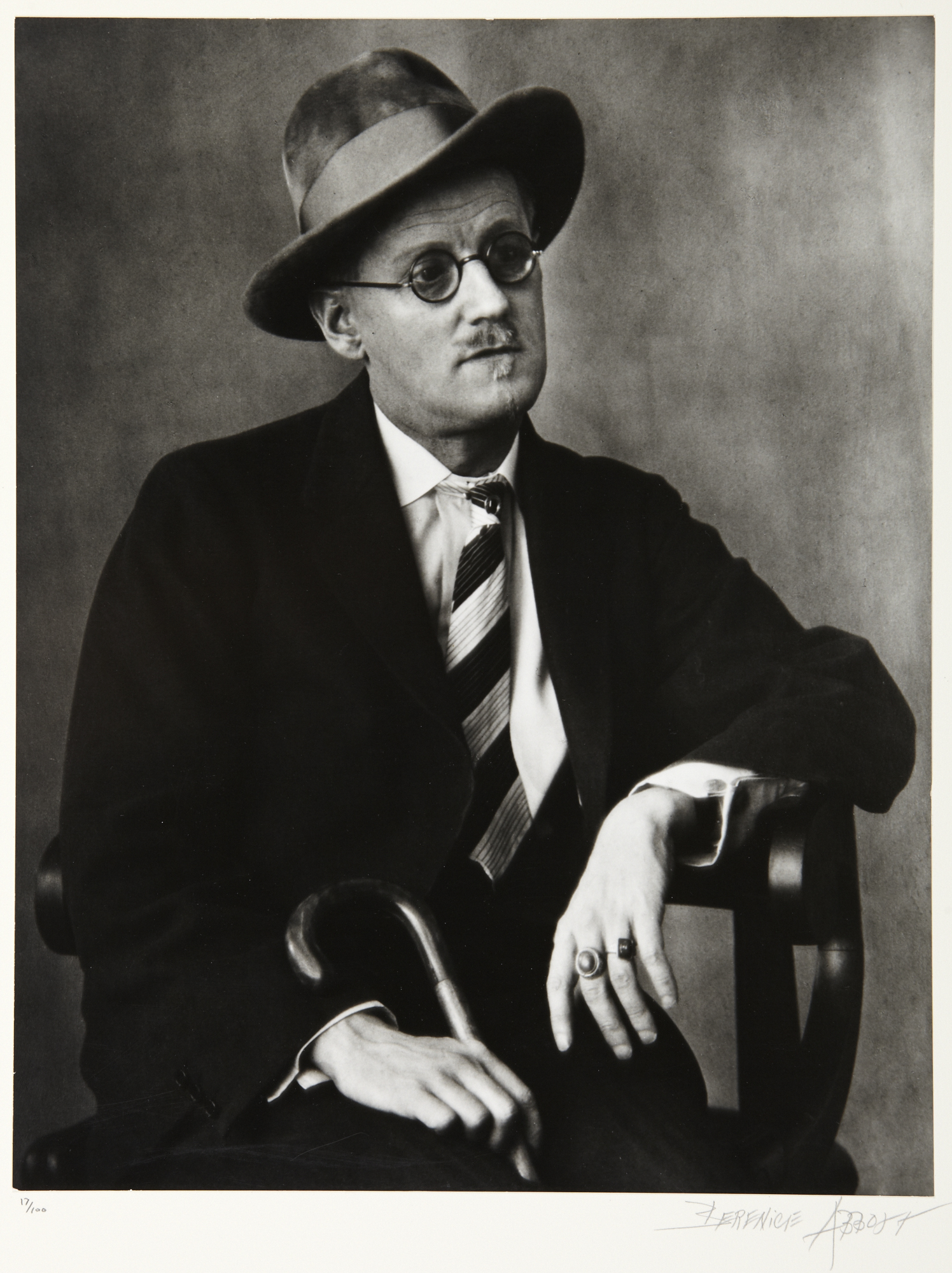

Each subject was extremely important to her. "I wasn't trying to make a still life of them," she has said, "but a person. Its a kind of exchange between people—it has to be—and I enjoyed it." (2) Formal posing was totally foreign to her approach. Her subjects tend to move casually; frequently they slouch. Occasionally perhaps captured in conversation or interaction with her, they strike self-assertive or deliberately playful stances. Always she is a master at catching the telling gesture (the languid, listless hand of James Joyce) or the detail of dress or accessory (the elegant pince-nez of Mrs. Theodore van Rysselberghe and the large ring on her forefinger) that reveals character as strongly as face or eyes. Less frequently Abbott experimented with arbitrary cropping to create a mood, one to us redolent of the art deco aesthetic first formally presented to Paris and the world in 1925 at L'Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes. How could she not be aware of and sensitive to the international movements in art that crowded the Paris horizon? Yet, through it all, we sense a serious intelligence and a sturdy individuality developing and gathering force.

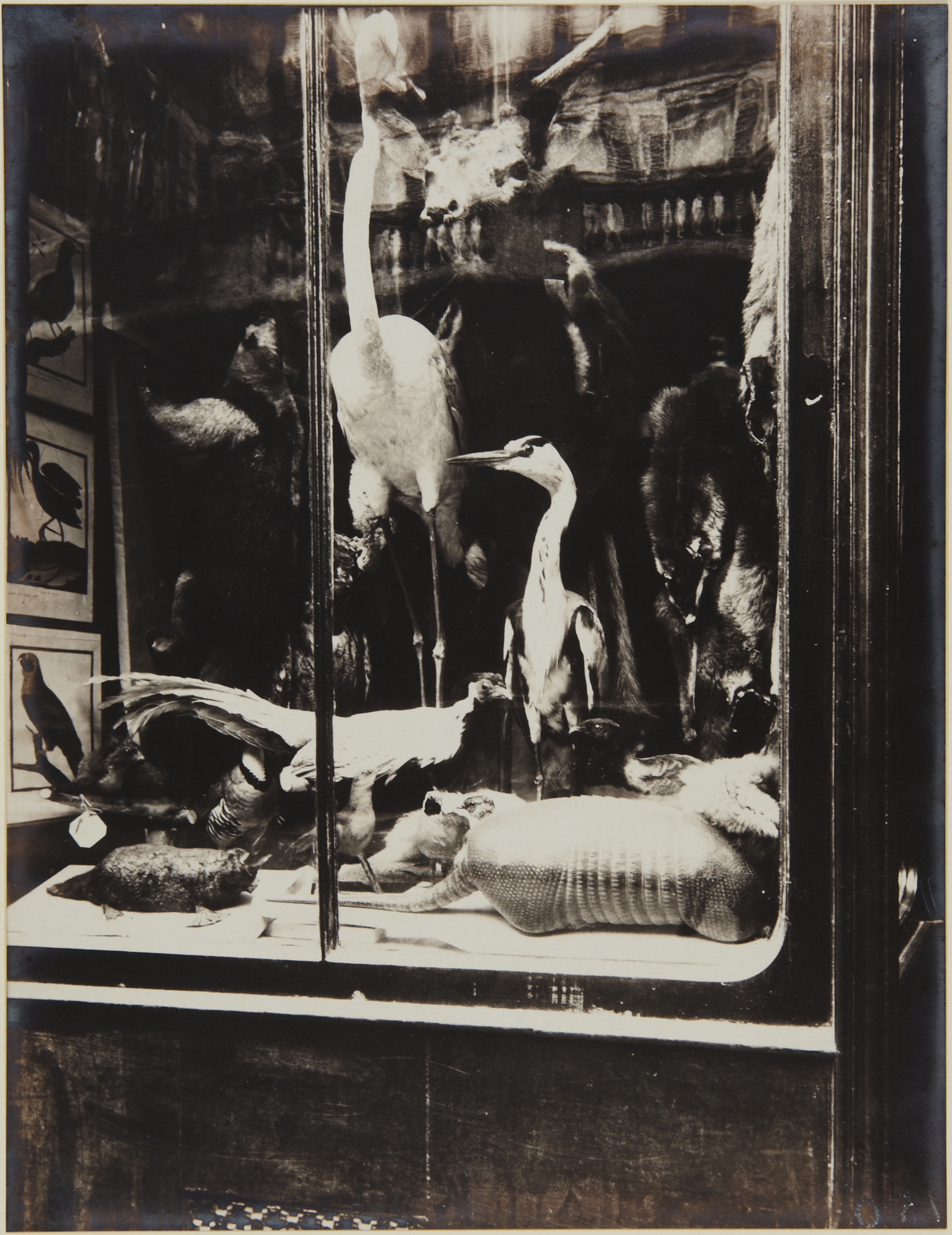

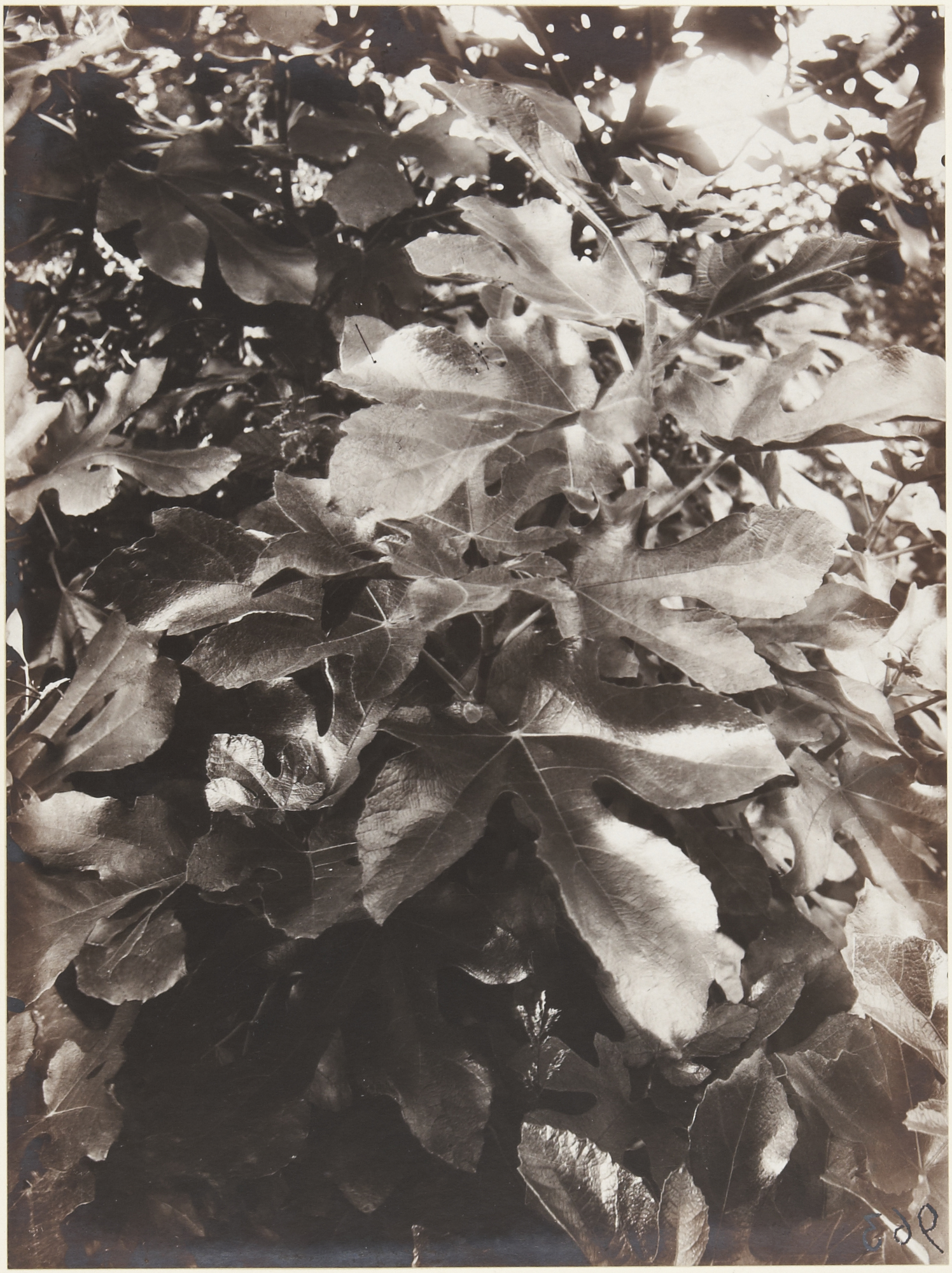

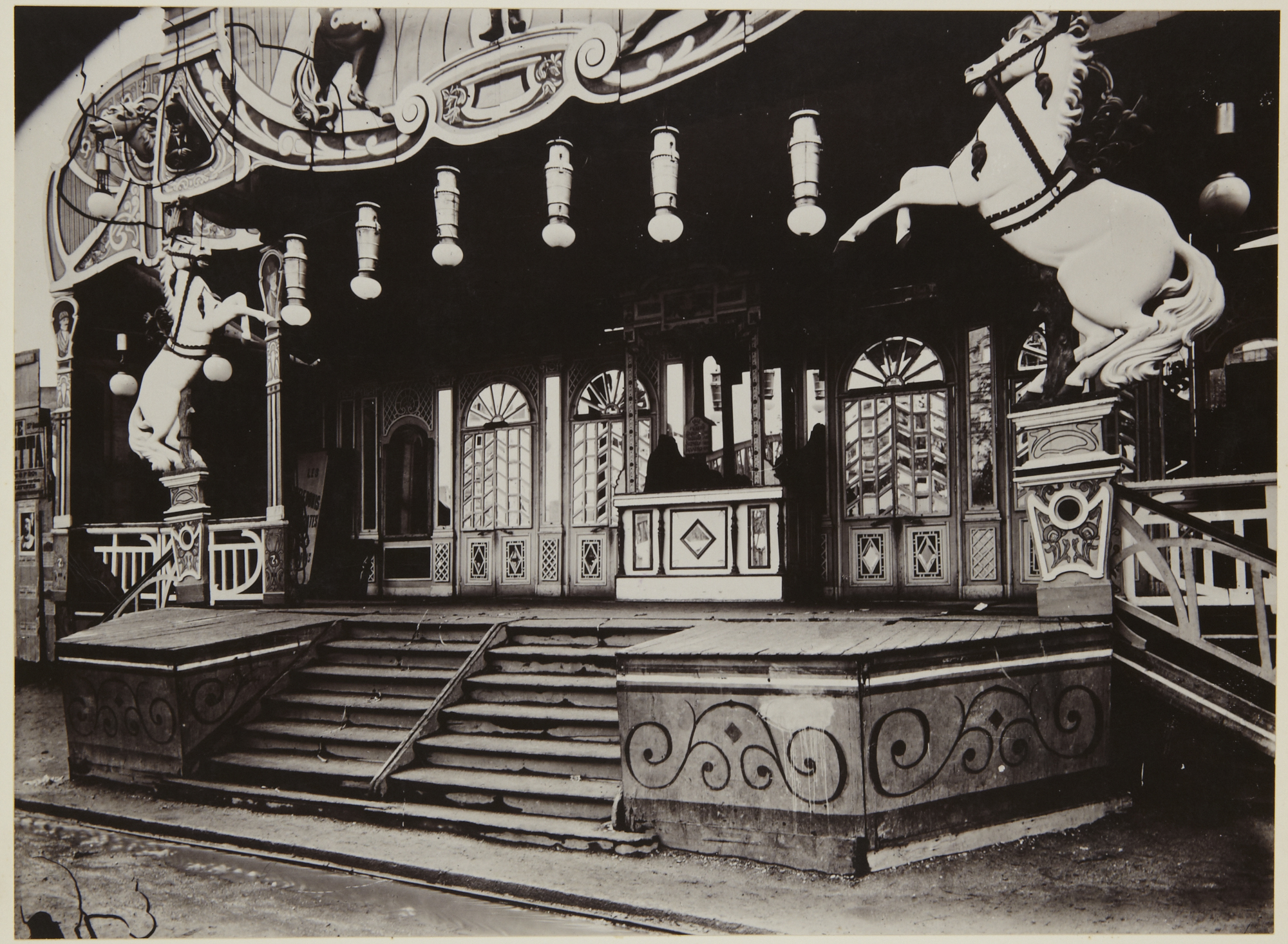

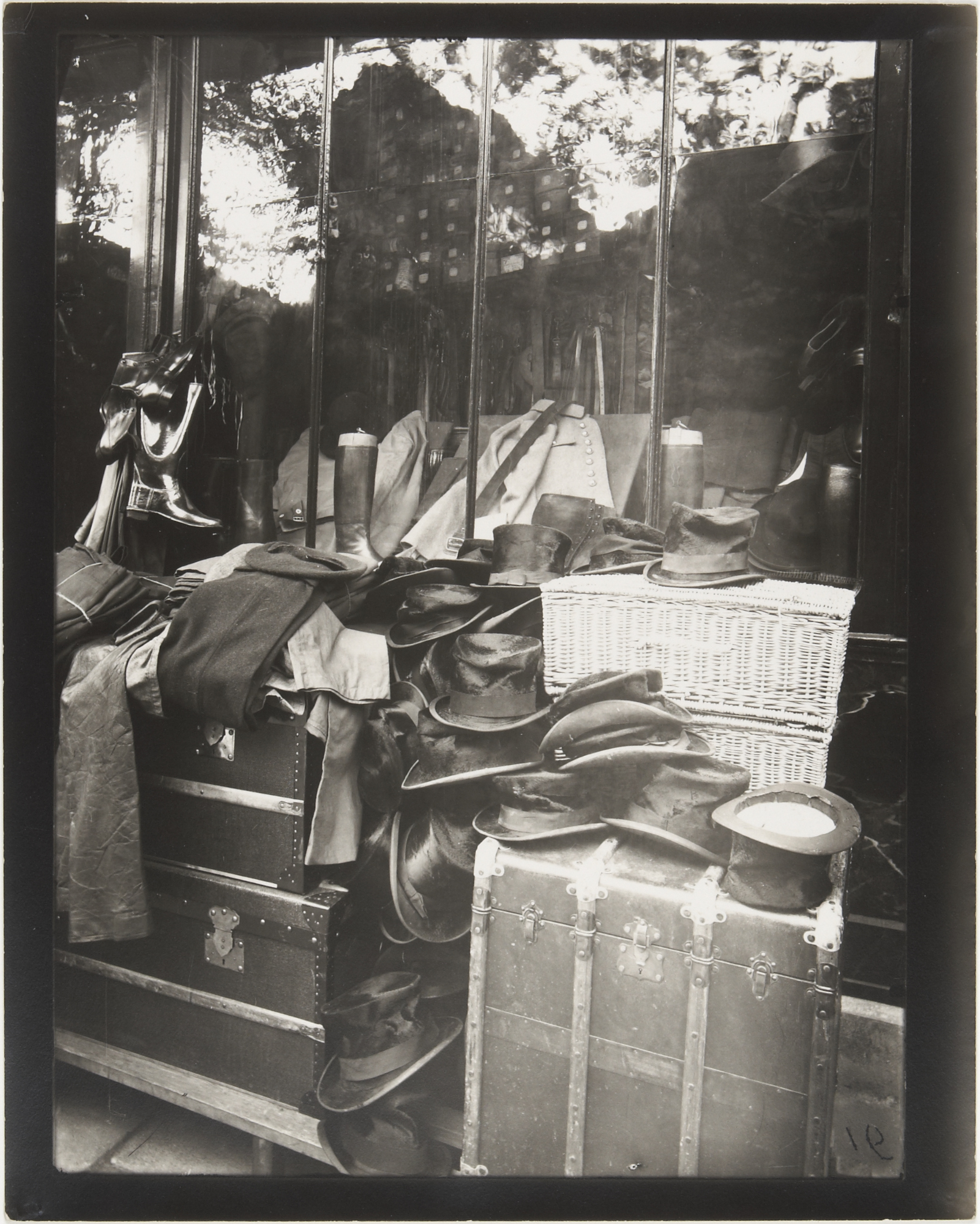

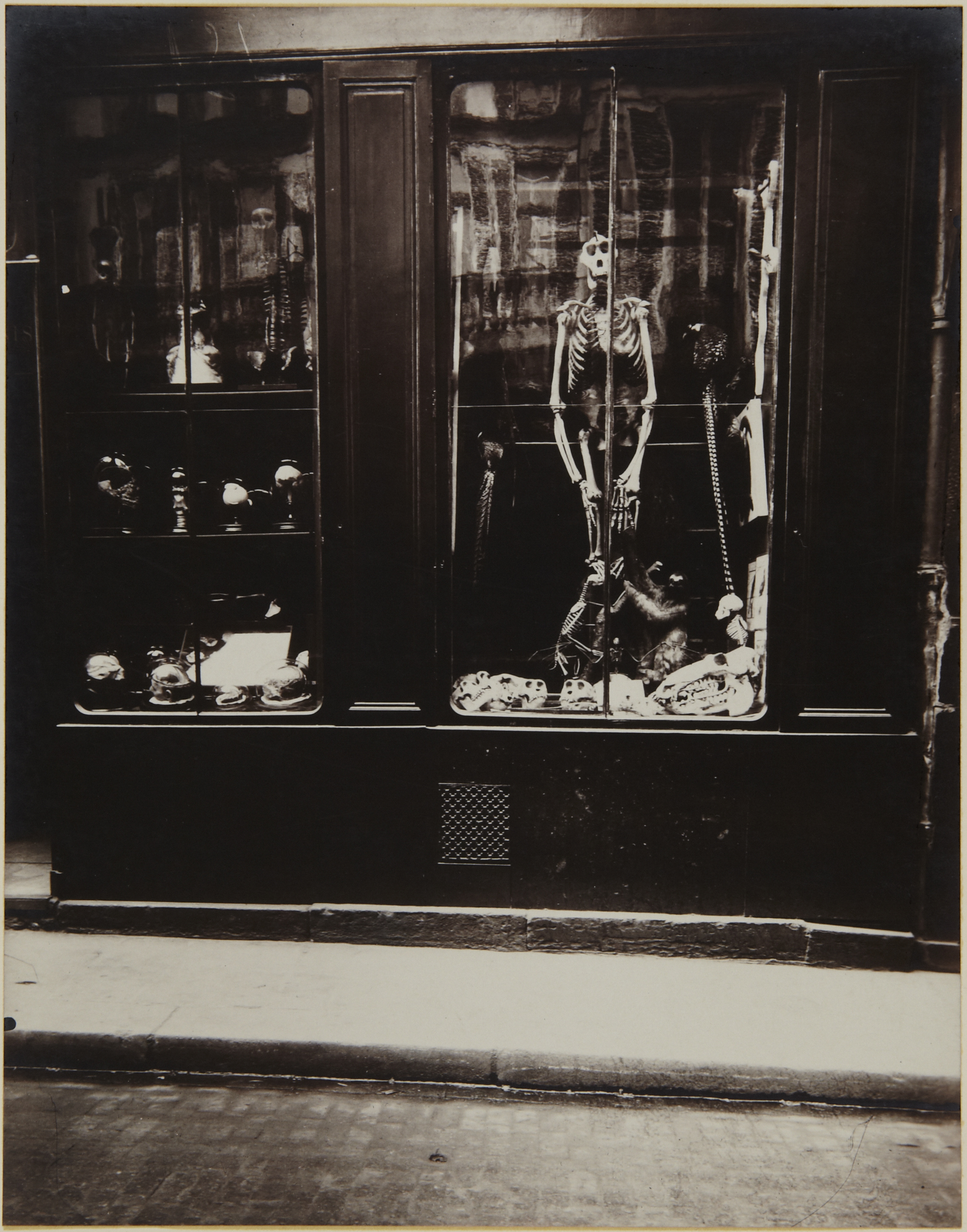

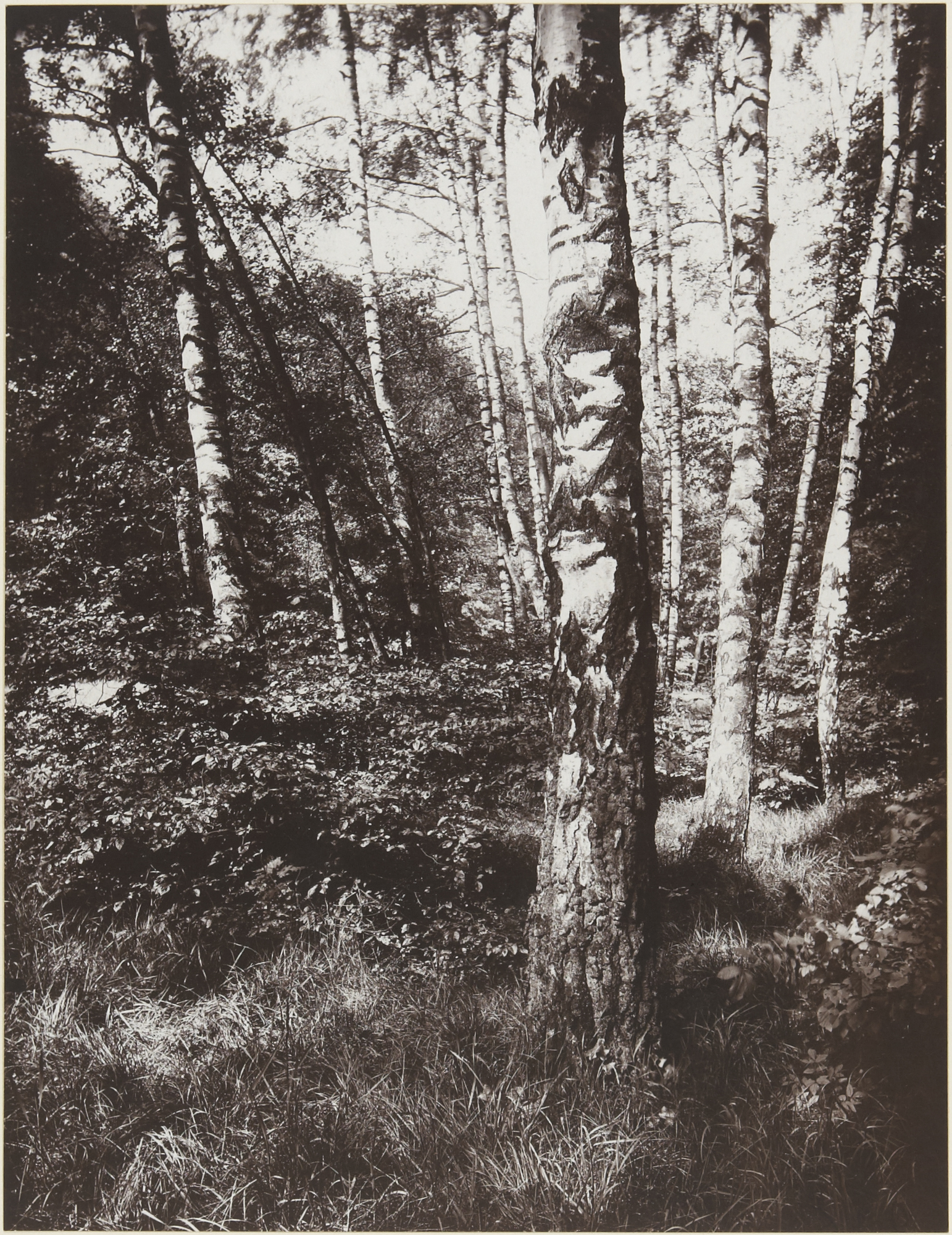

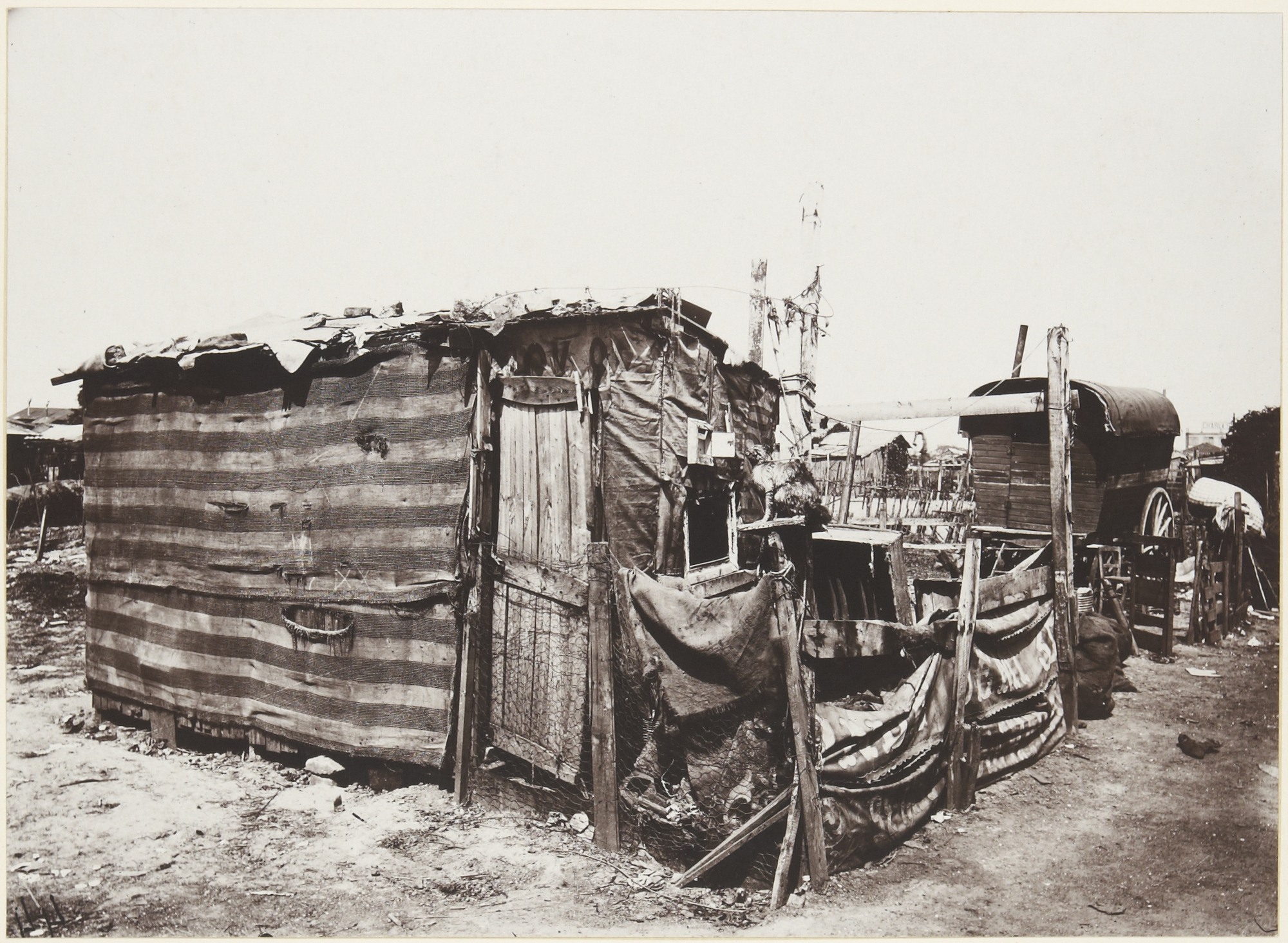

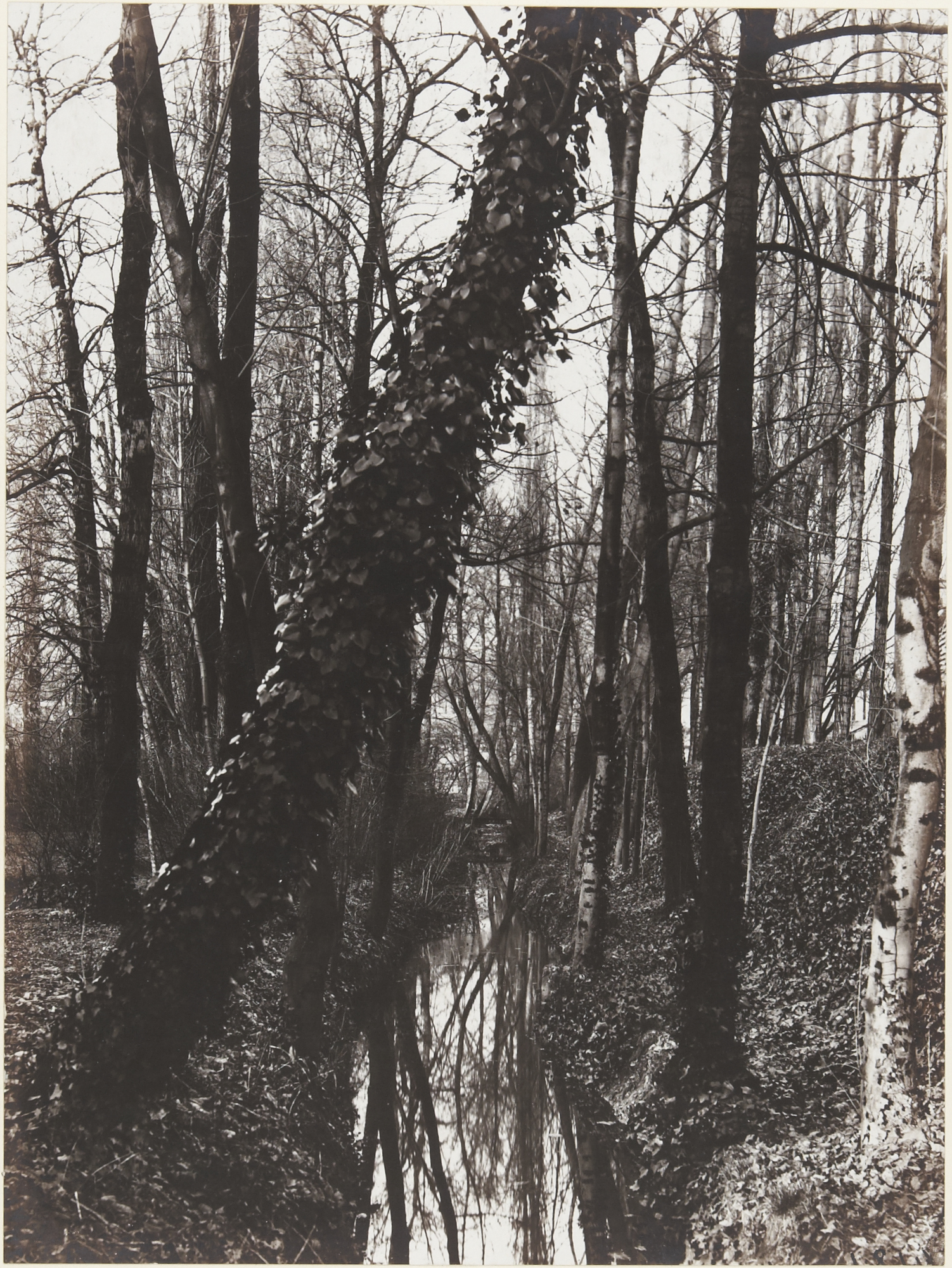

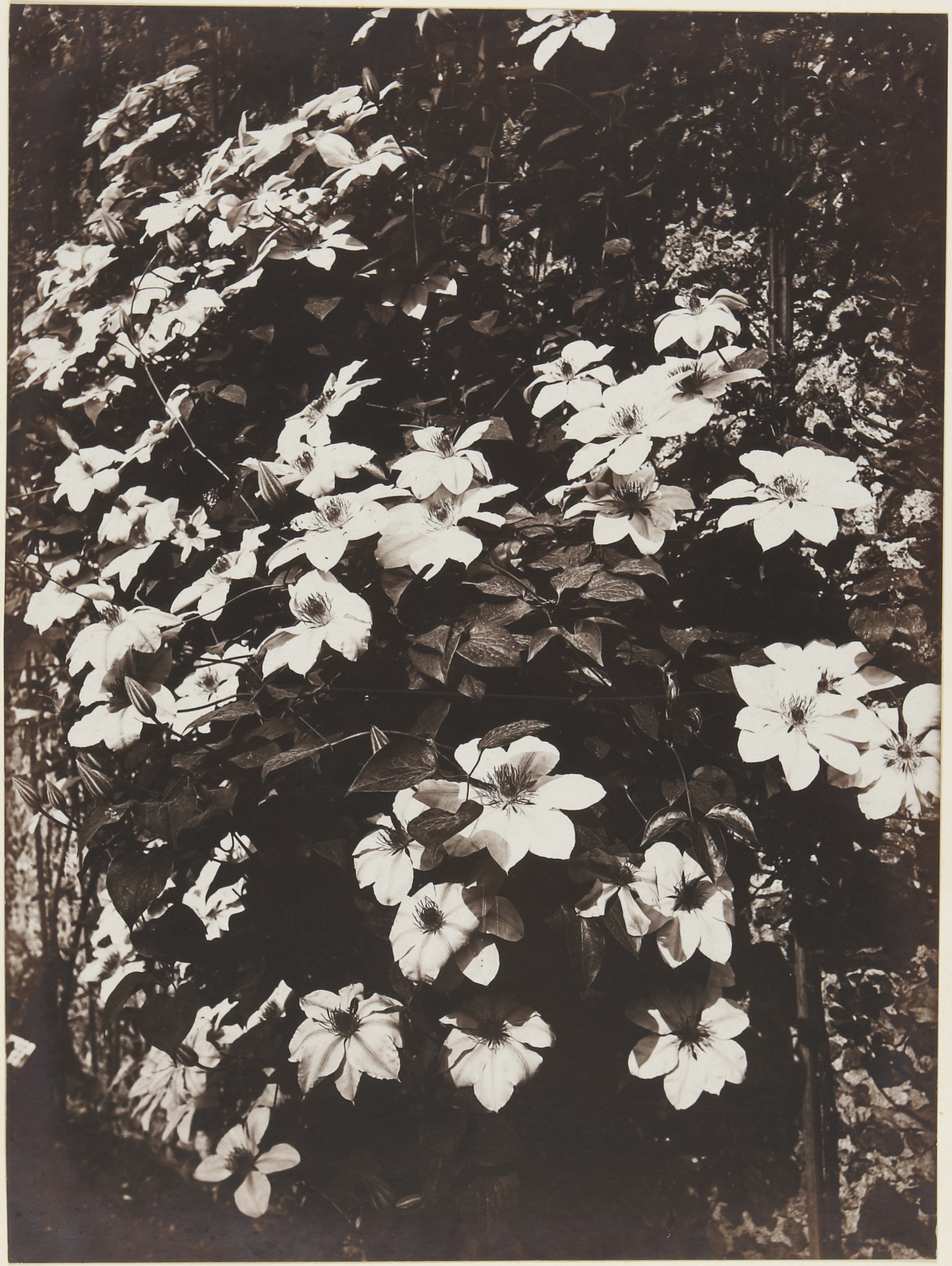

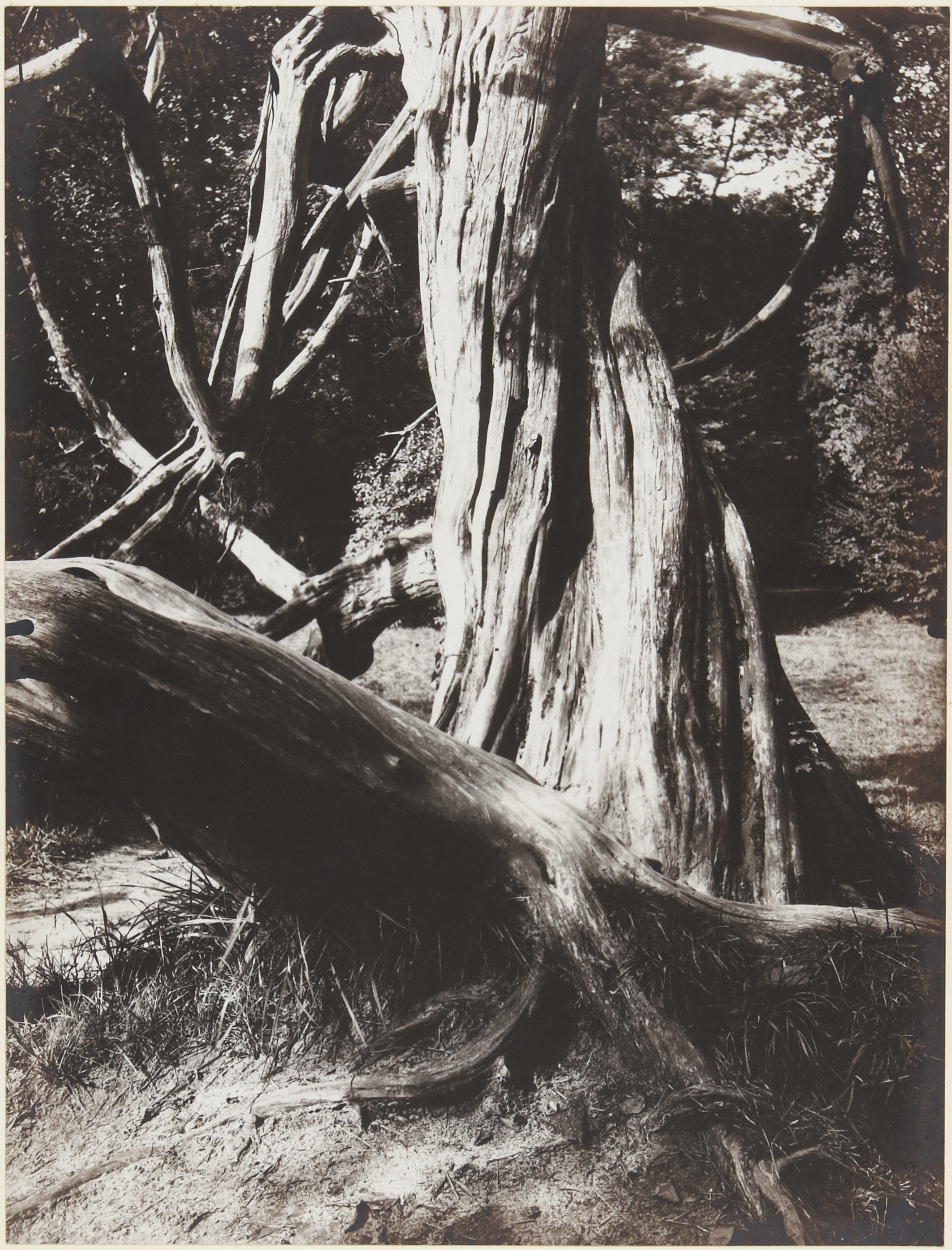

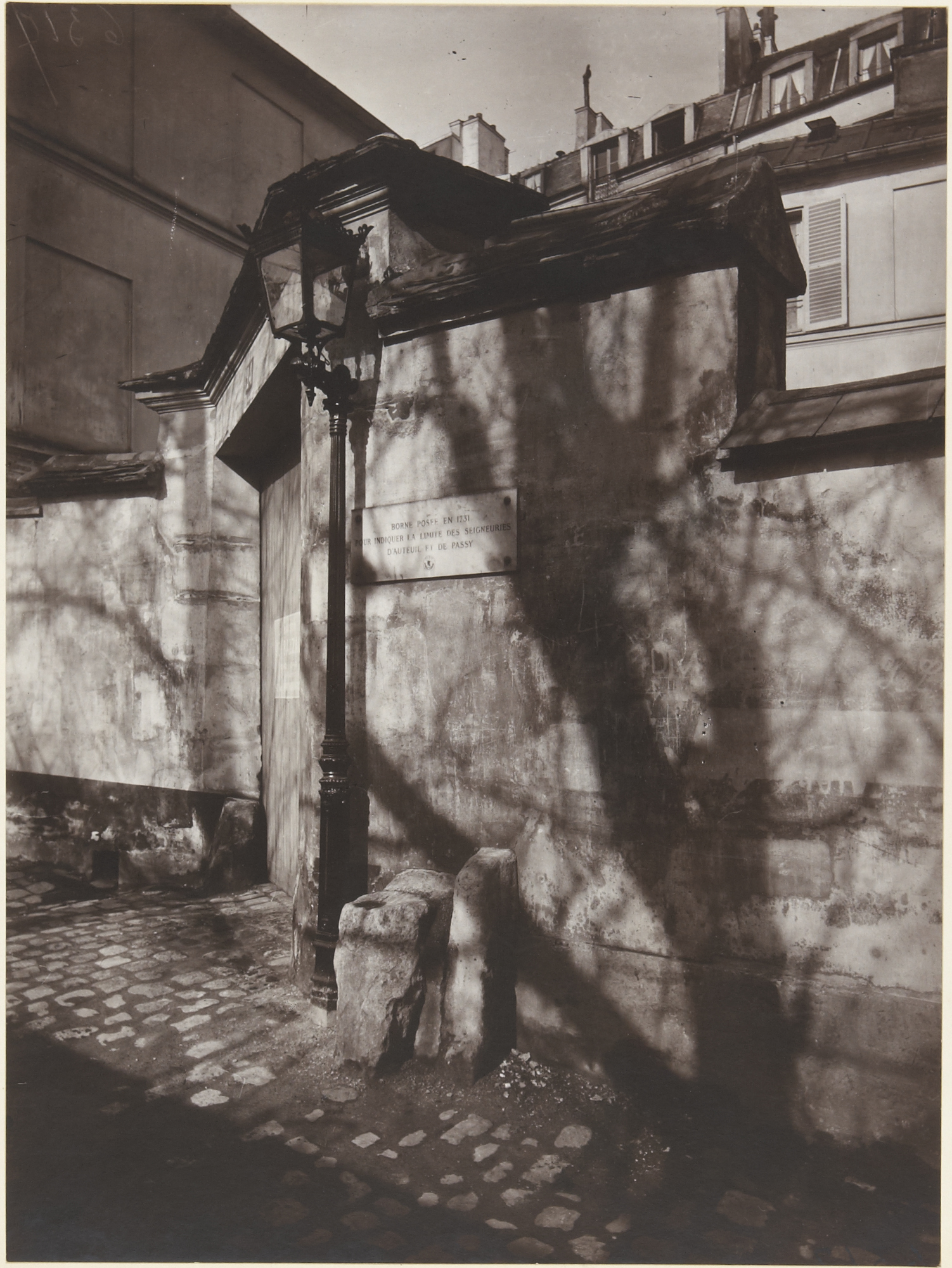

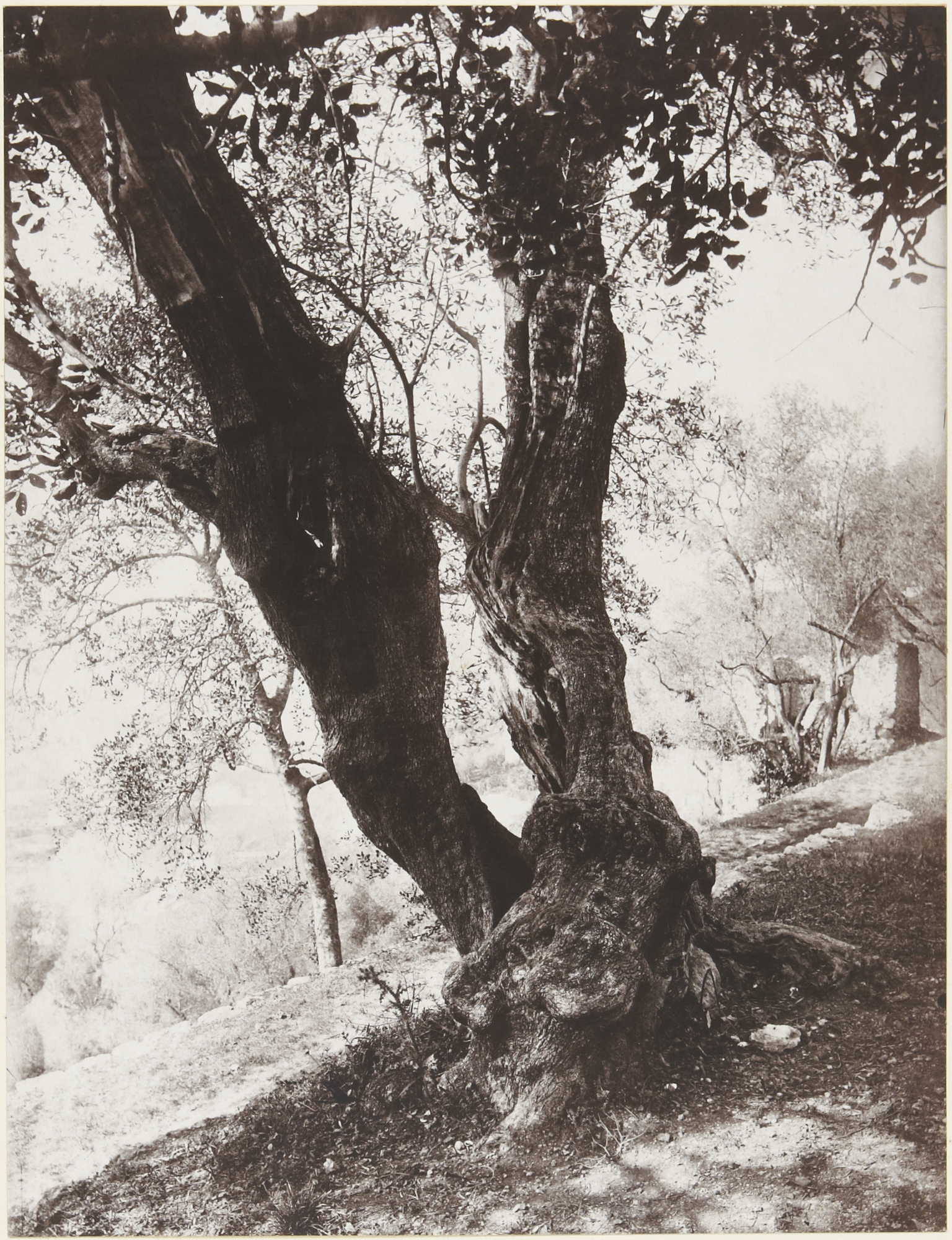

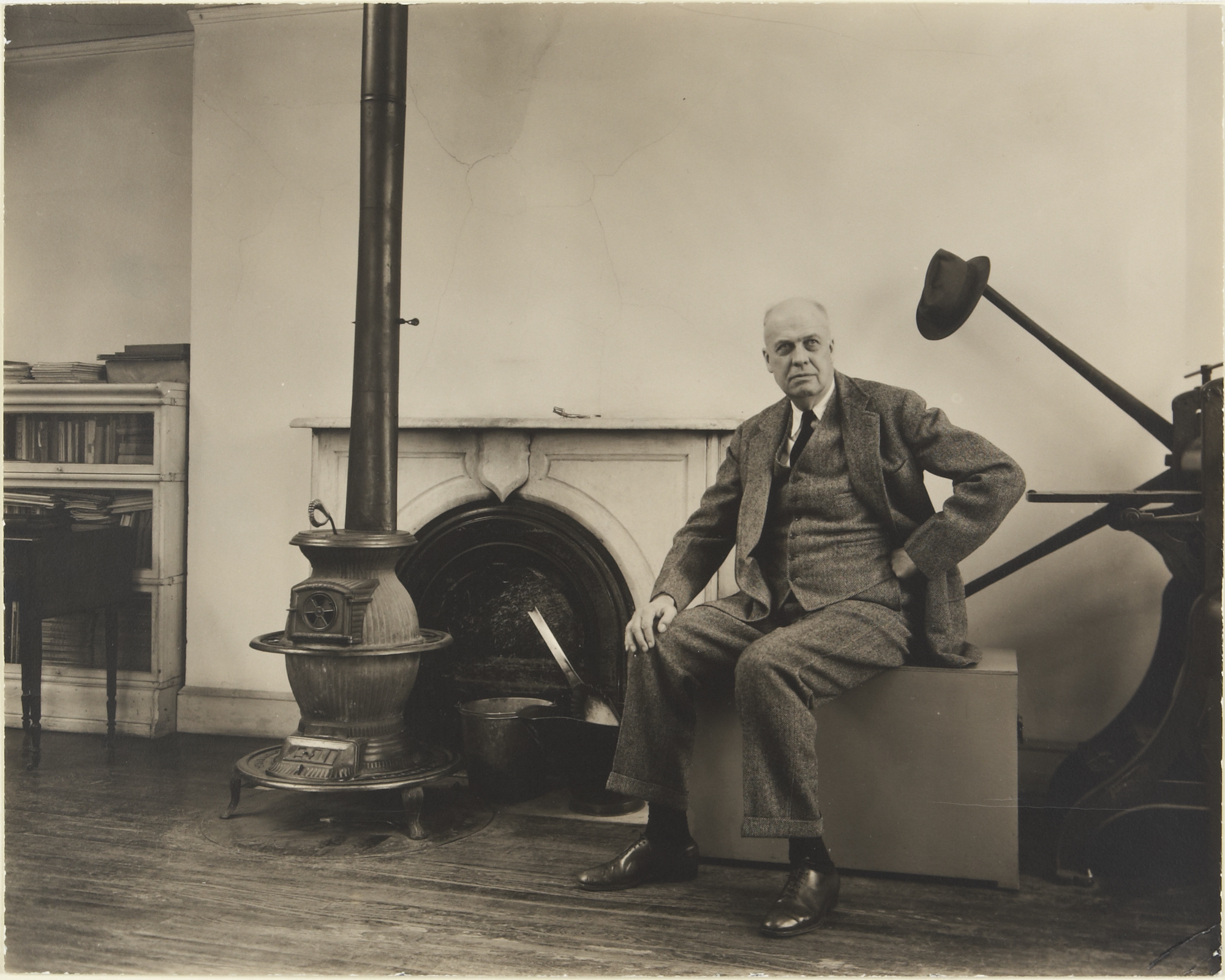

The years in Paris also brought an obsession into Abbott's life—the work of the French photographer Eugene Atget (1857–1927). Now some fifty years after his death honored by exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, he was largely unknown or rejected in Paris during the 1920s. (Even as late as 1967 or 1968, Abbott says, the French authorities rejected the Atget collection when she offered it to them through the French Minister of Culture, André Malraux.) Abbott had first become aware of the work of this unrecognized master of photography through Man Ray. The impact of Atget's work on her was immediate and she periodically bought his photographs, as many as she could afford, for a few francs each. After Atget's death she purchased his collection of some 10,000 images—both prints and negatives—from his closest friend, André Calmette. A labor of love followed as Abbott saw that each glass plate negative was cleaned and stored in a numbered glassine envelope. Then she began her long and until recently quite fruitless campaign to have Atget's work recognized. The resistance she met reveals the attitudes of the art world of the day: a preoccupation with abstraction, an abhorrence and denigration of realism as trivial and trite, and grave doubts as to the legitimacy of photography as an art. (The September 1951 issue of Art News, for example introduced an article by Berenice Abbott with the rhetorical questions, "Does photography belong in museums? In fact, is it an art at all?") (3) Abbott's fight for Atget's recognition demanded her time, attention, persistence, and self-sacrifice, often at the expense of her own career.

Despite her success in Paris, by 1929 Abbott was ready to return home. On a visit to America she became excited by New York city. She has said that she became interested in the States from a distance, that some persons abroad become fascinated with their own country. She had left her homeland out of frustration with a country that offered very little encouragement for the arts. Abbott feels that her relocation to Europe was an act of justified rebellion. Yet, she has said that "after years in Paris I found myself drawn by a certain nostalgia and an objective interest [in the United States] that crept up over the years." (4)

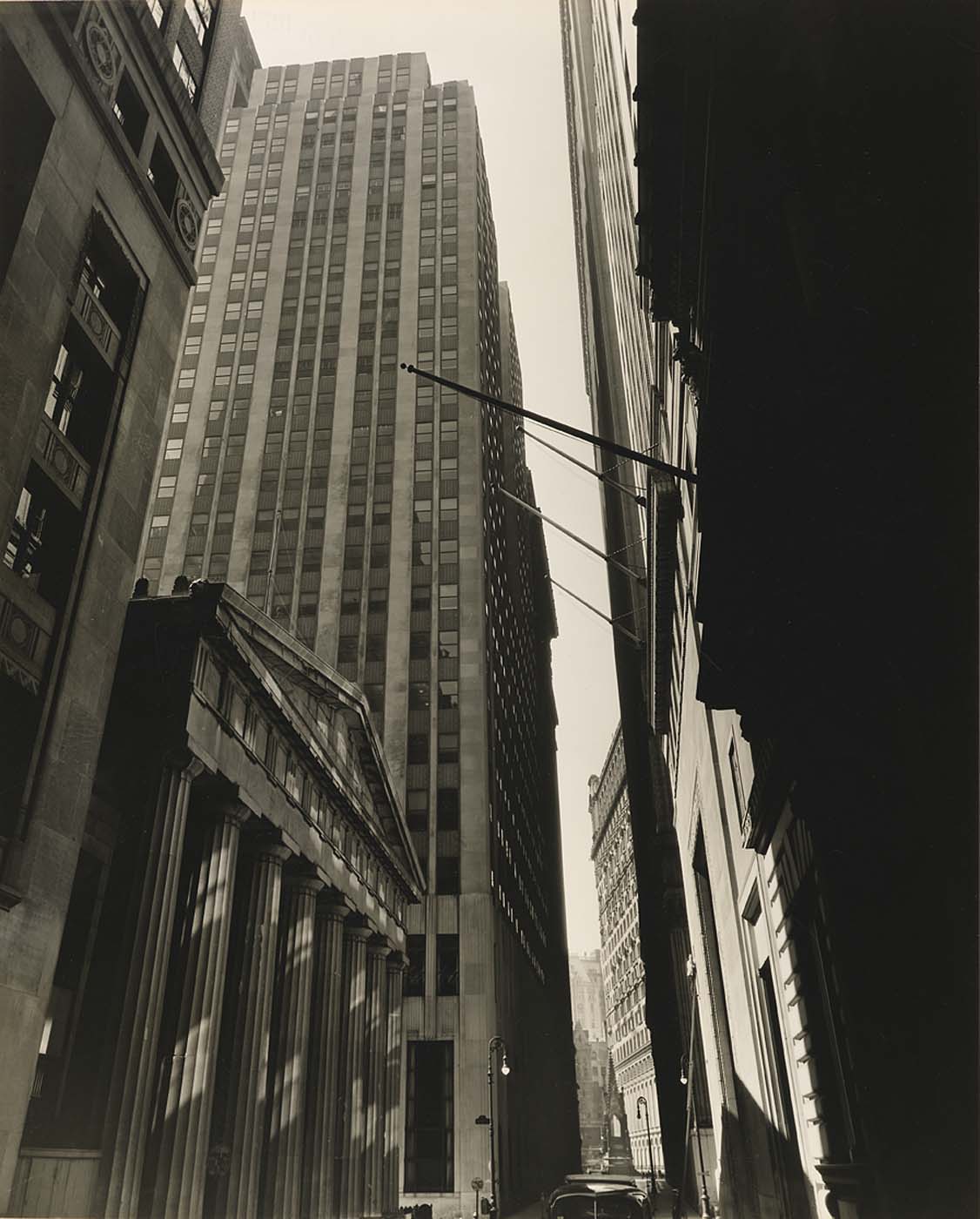

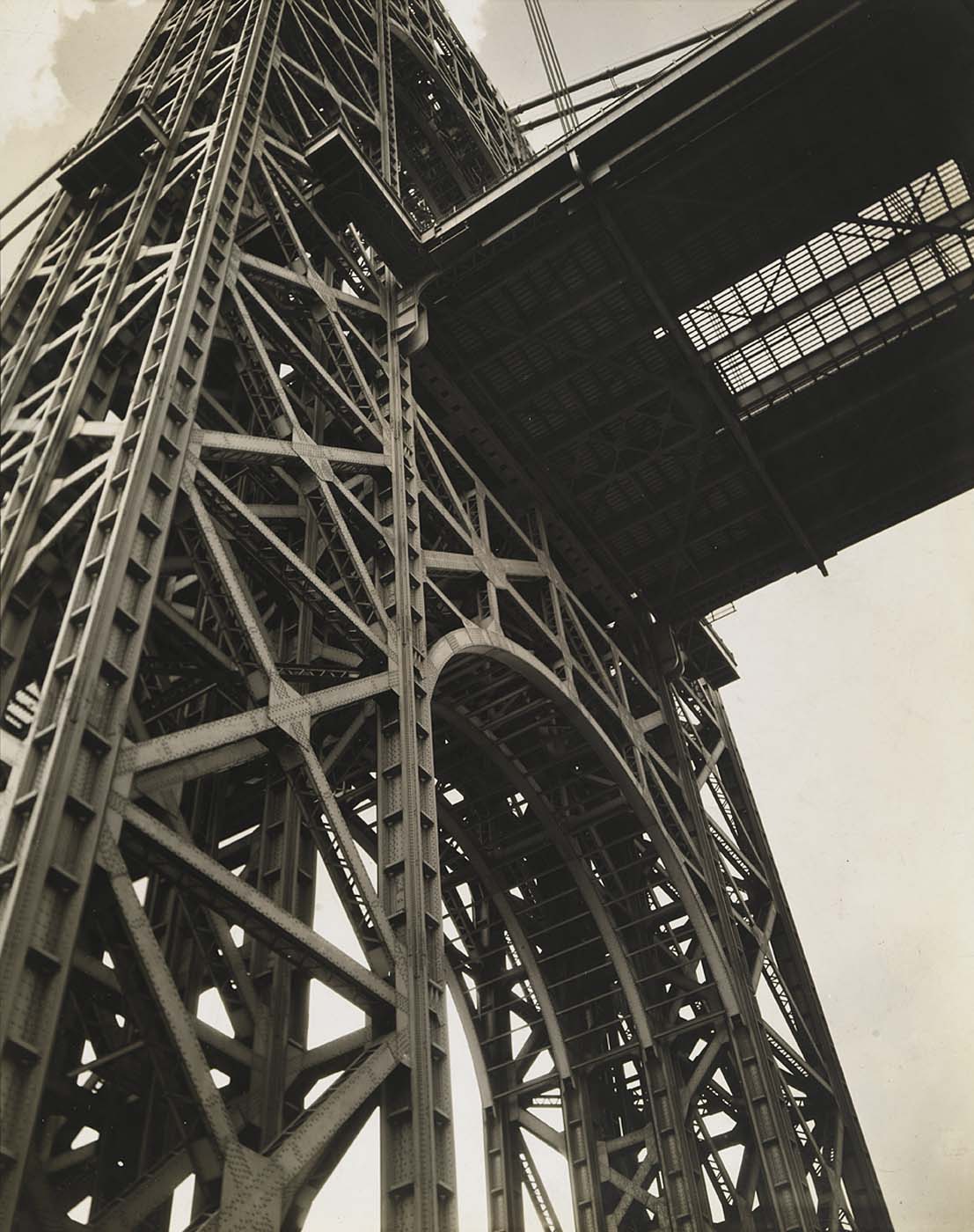

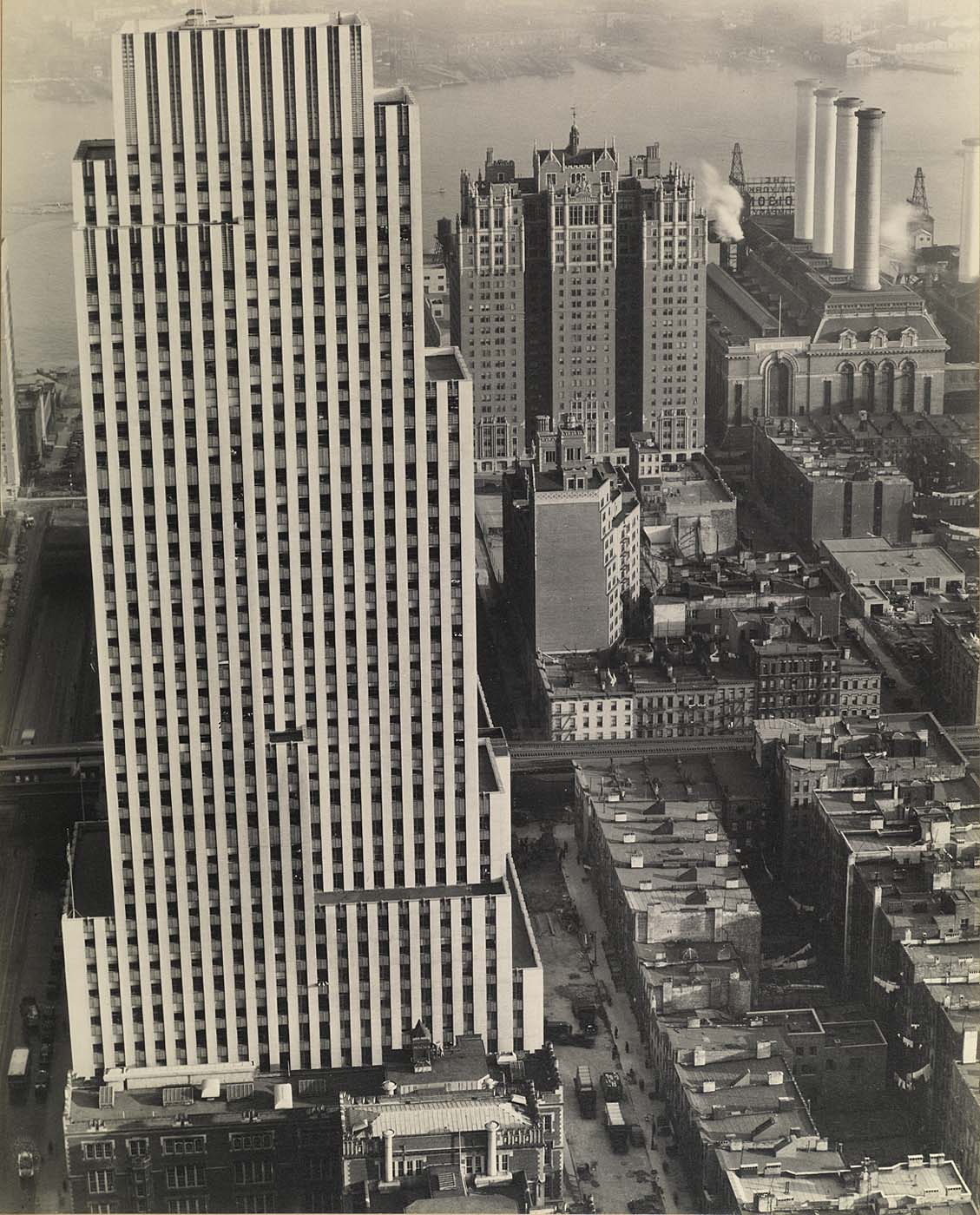

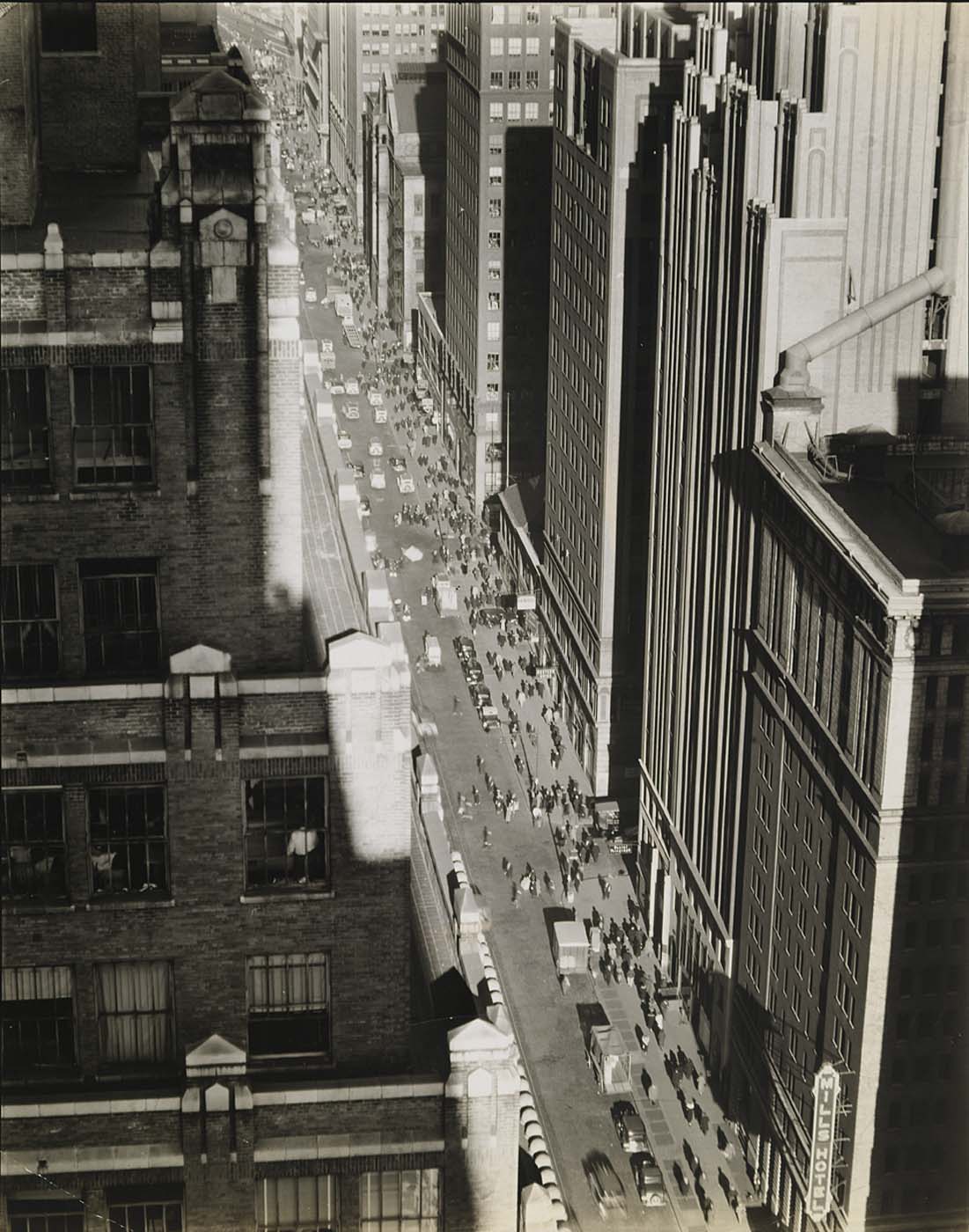

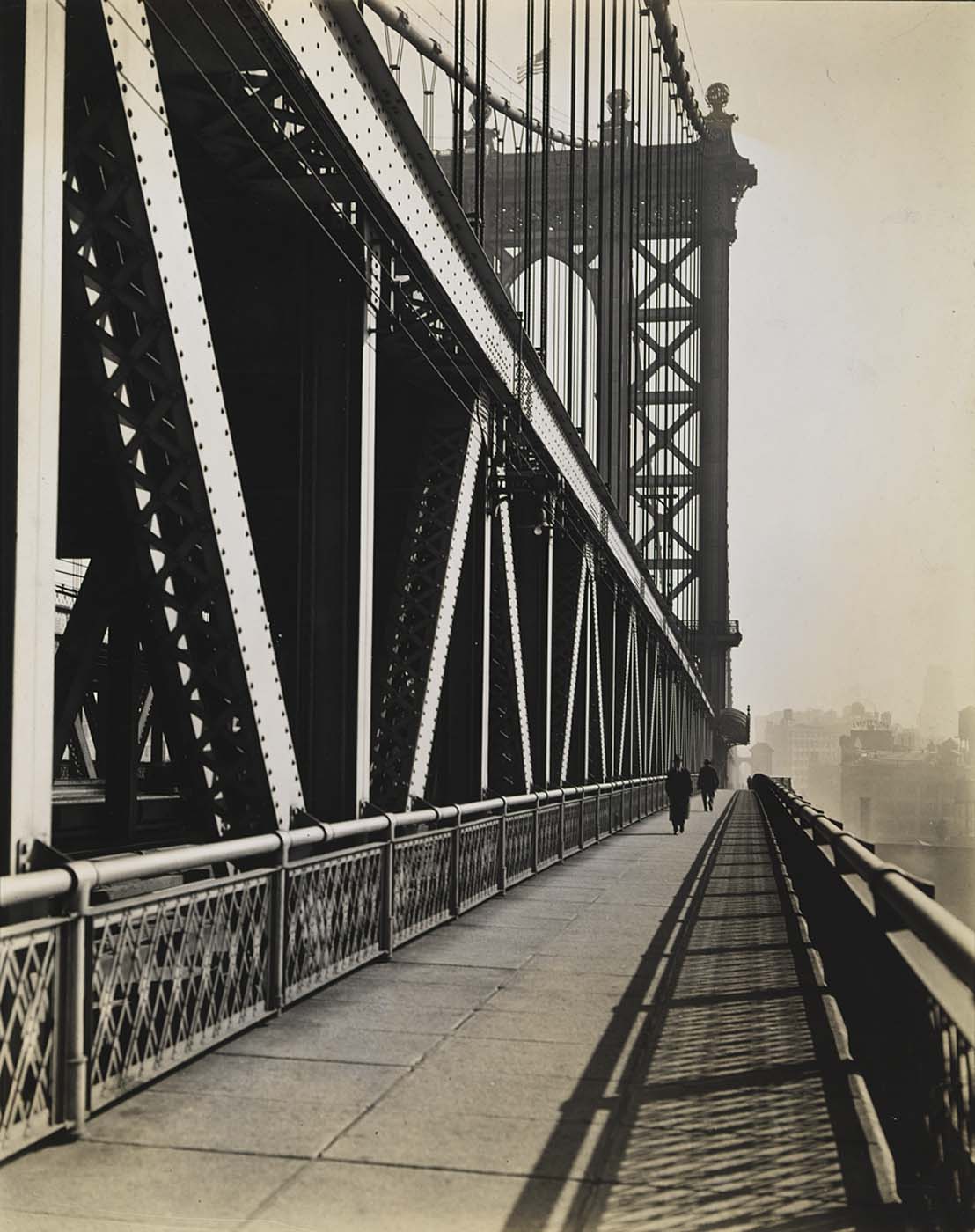

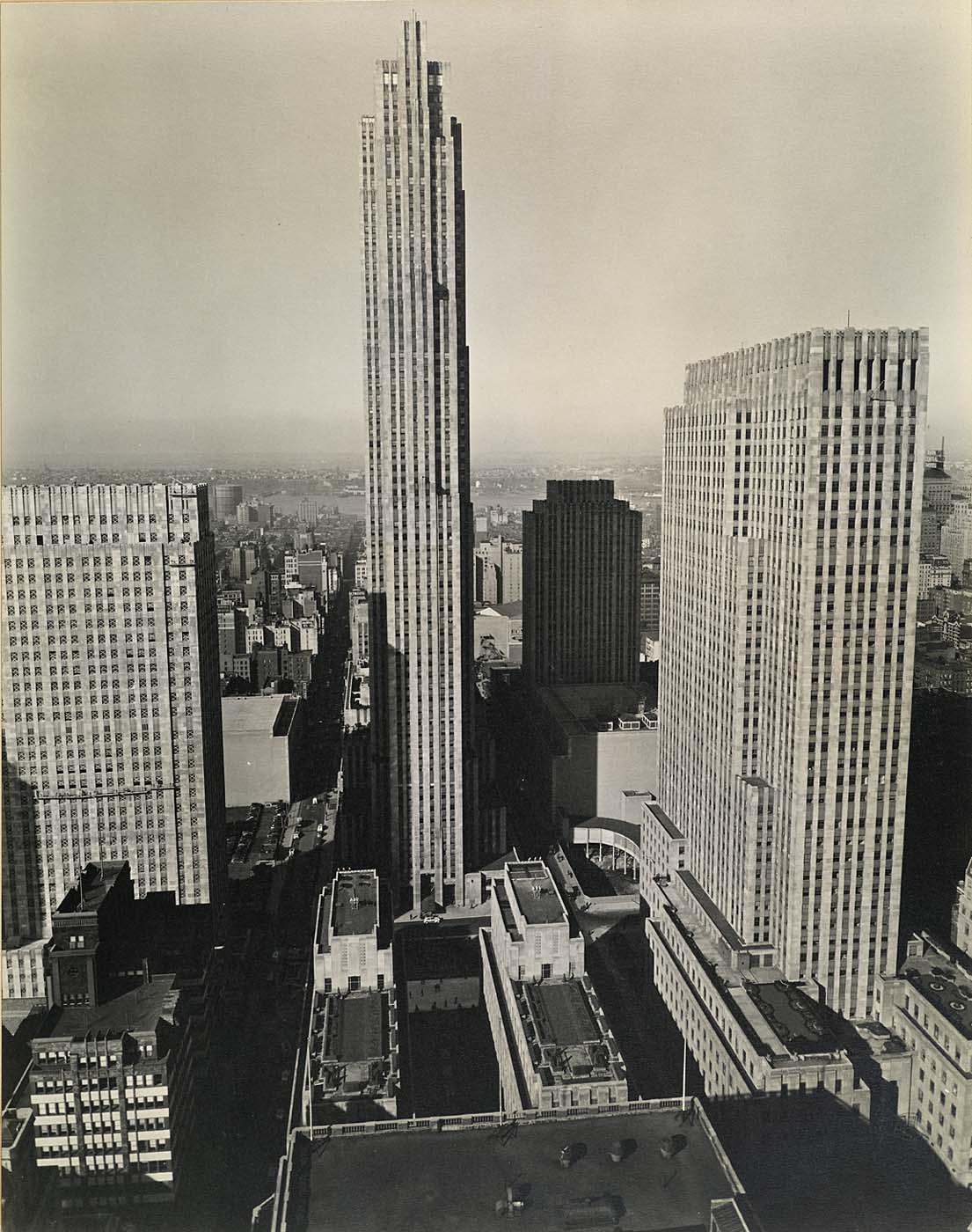

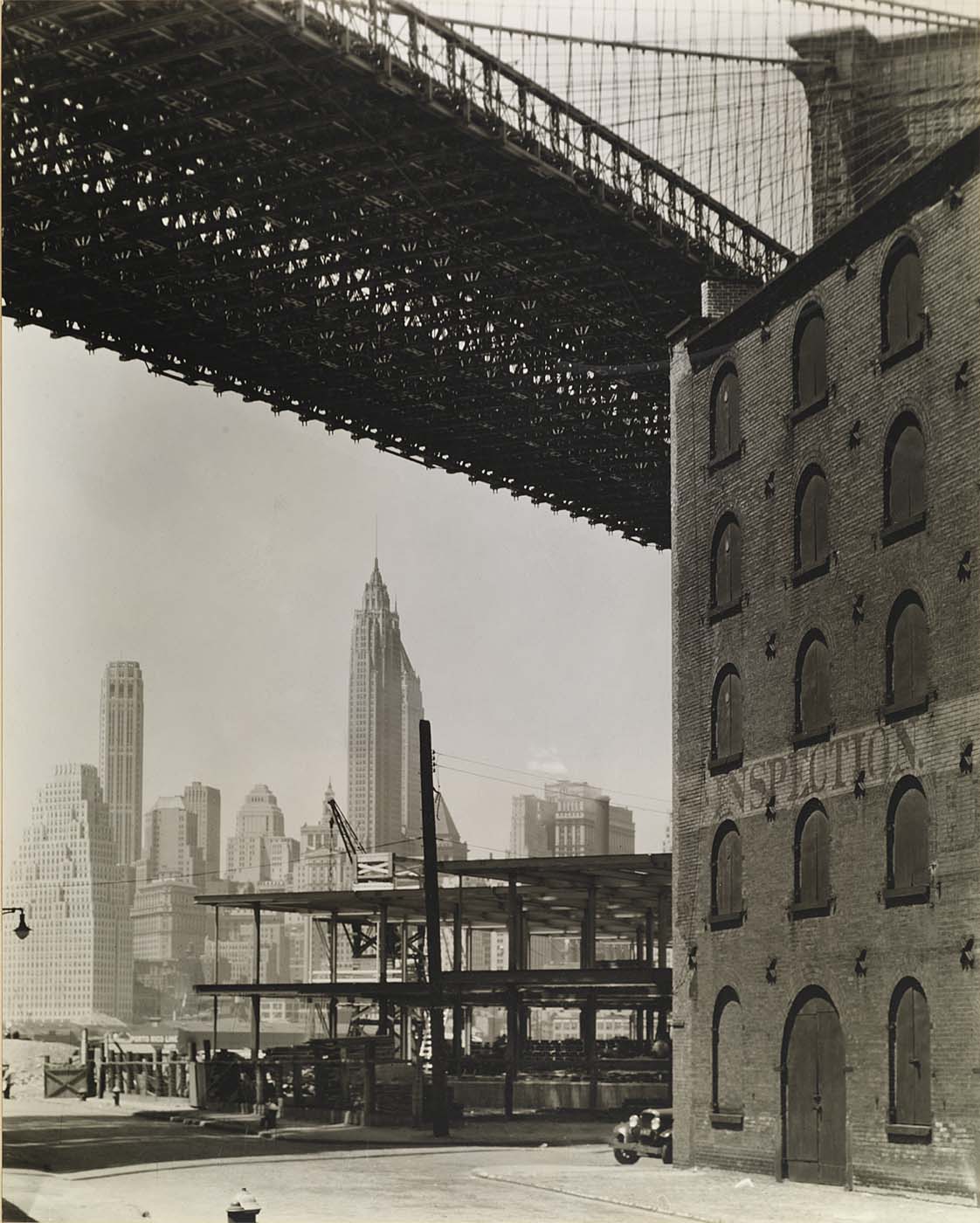

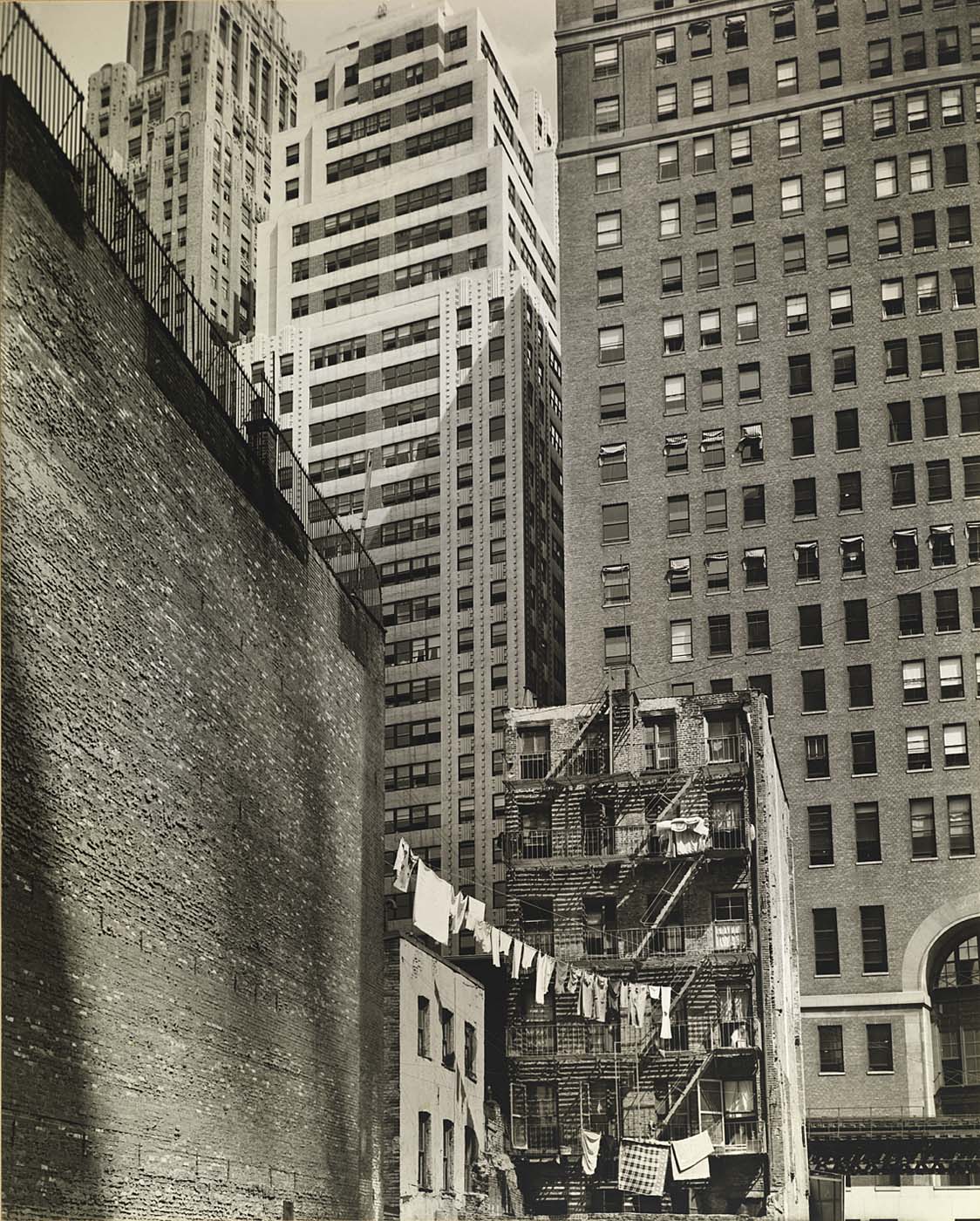

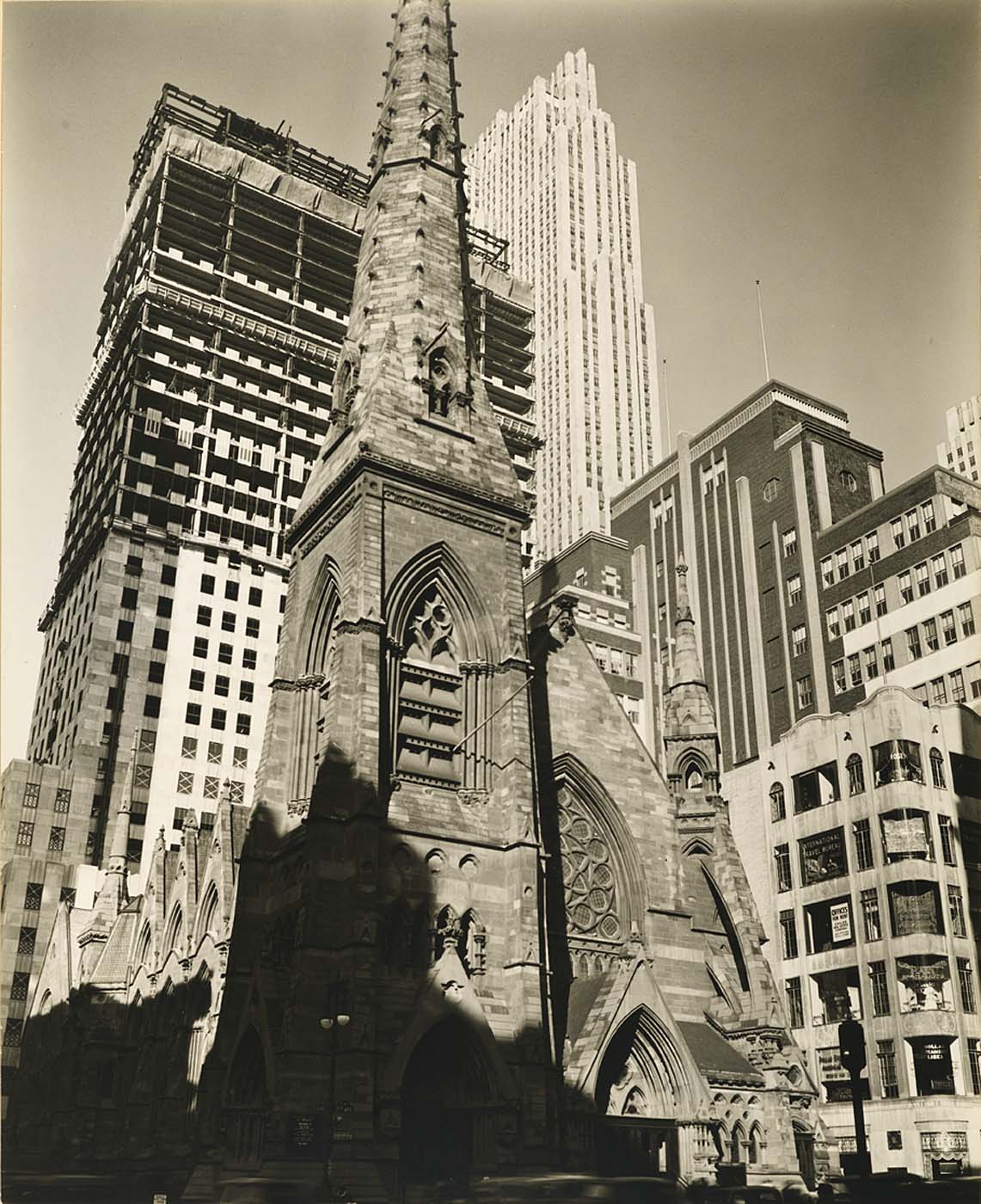

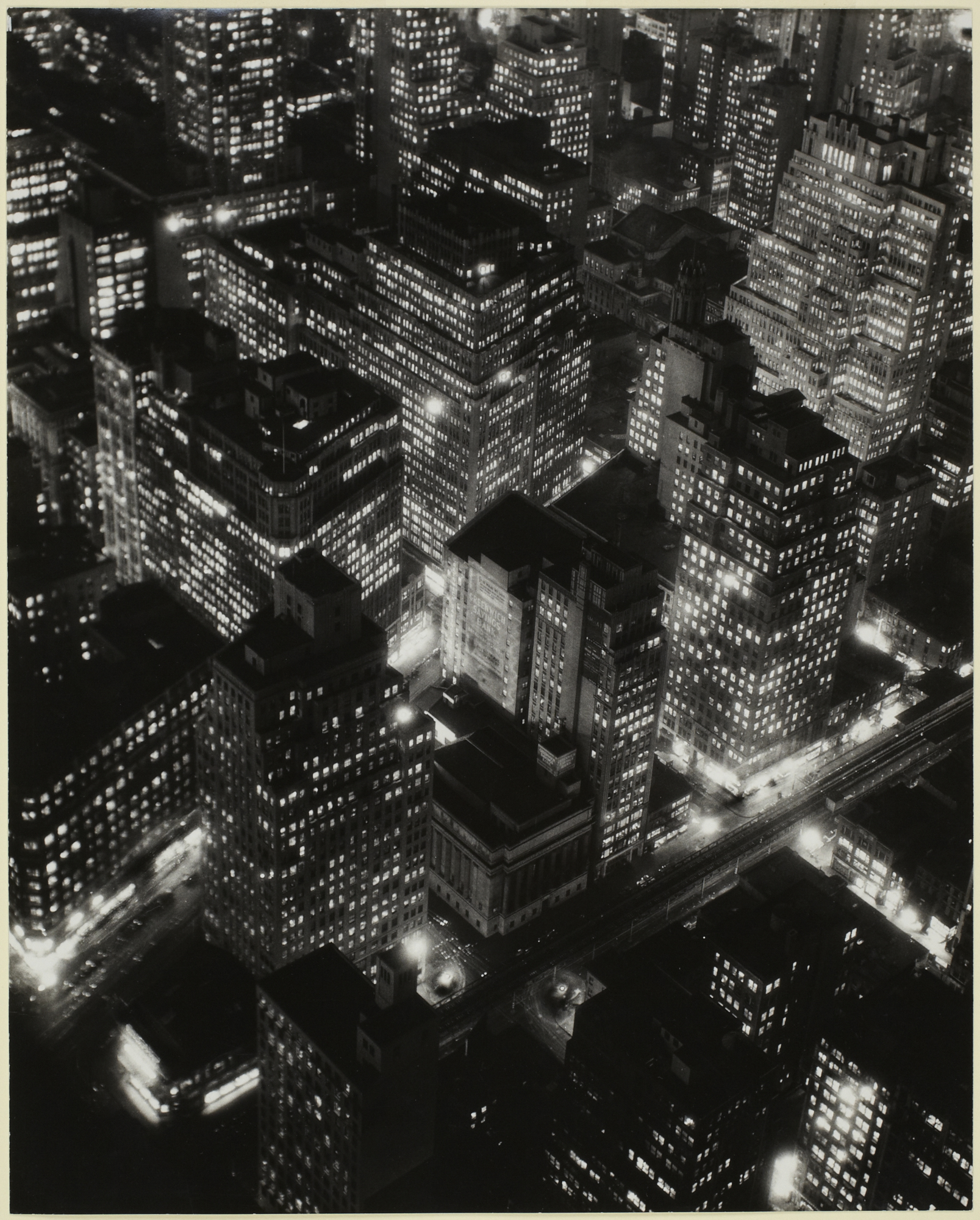

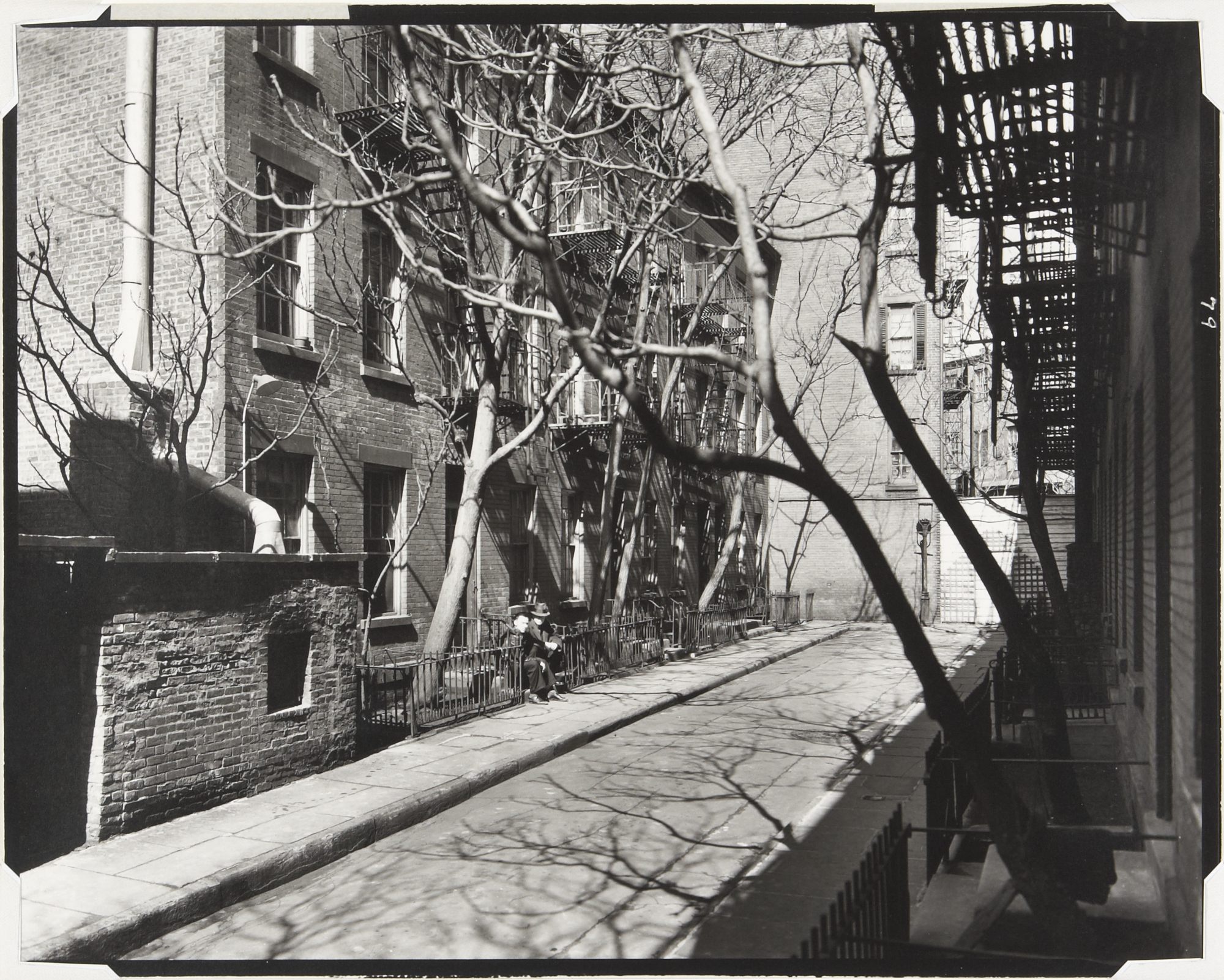

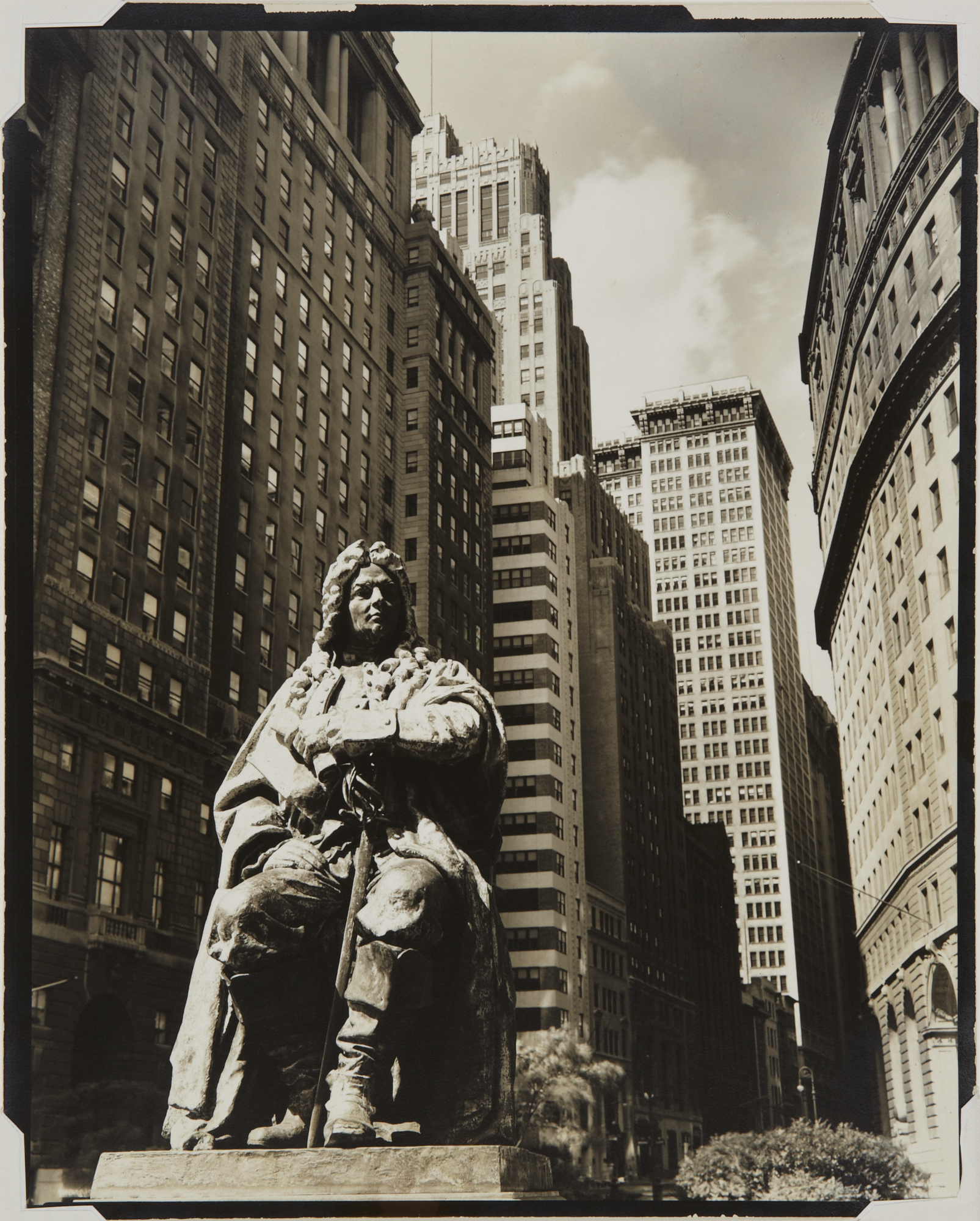

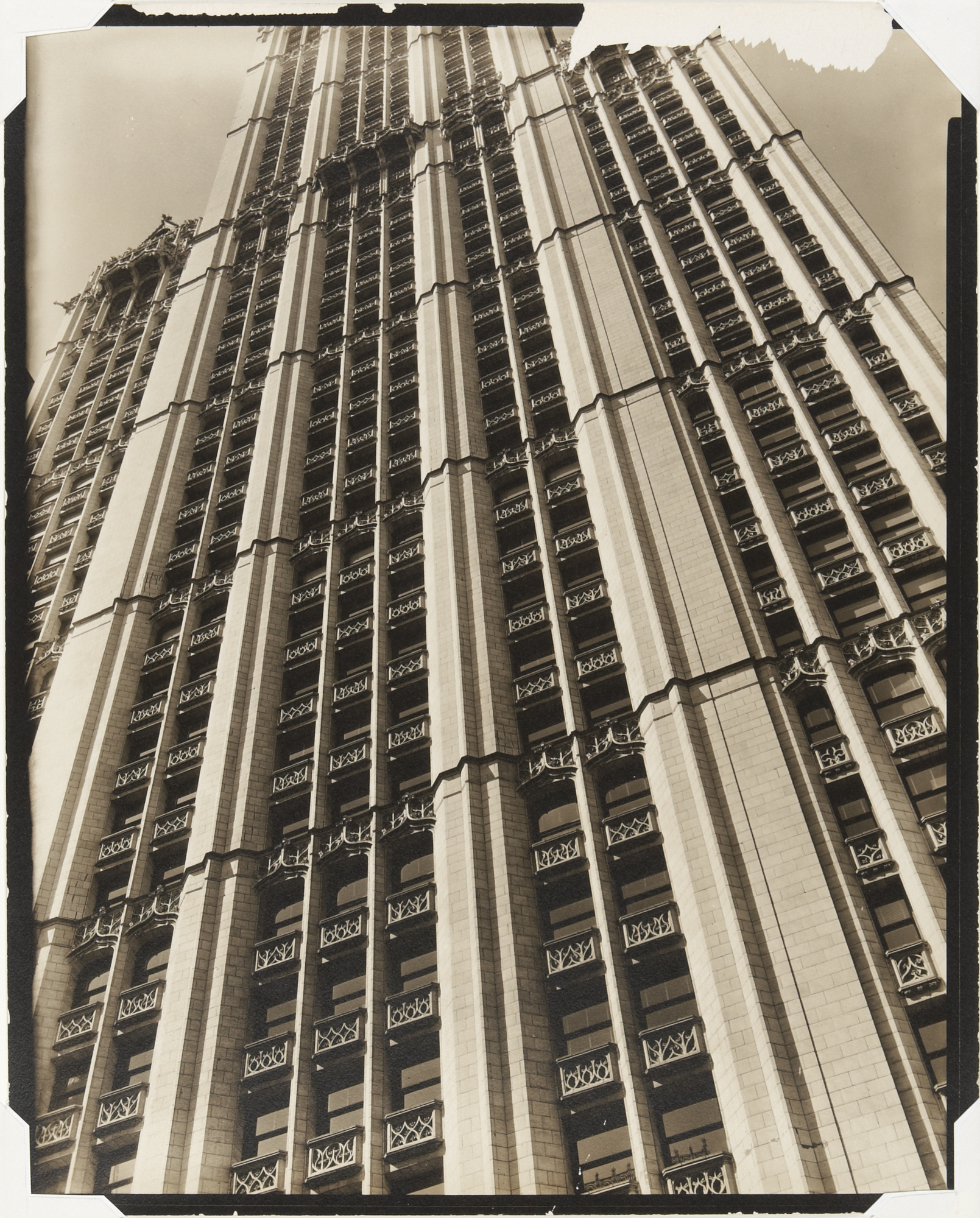

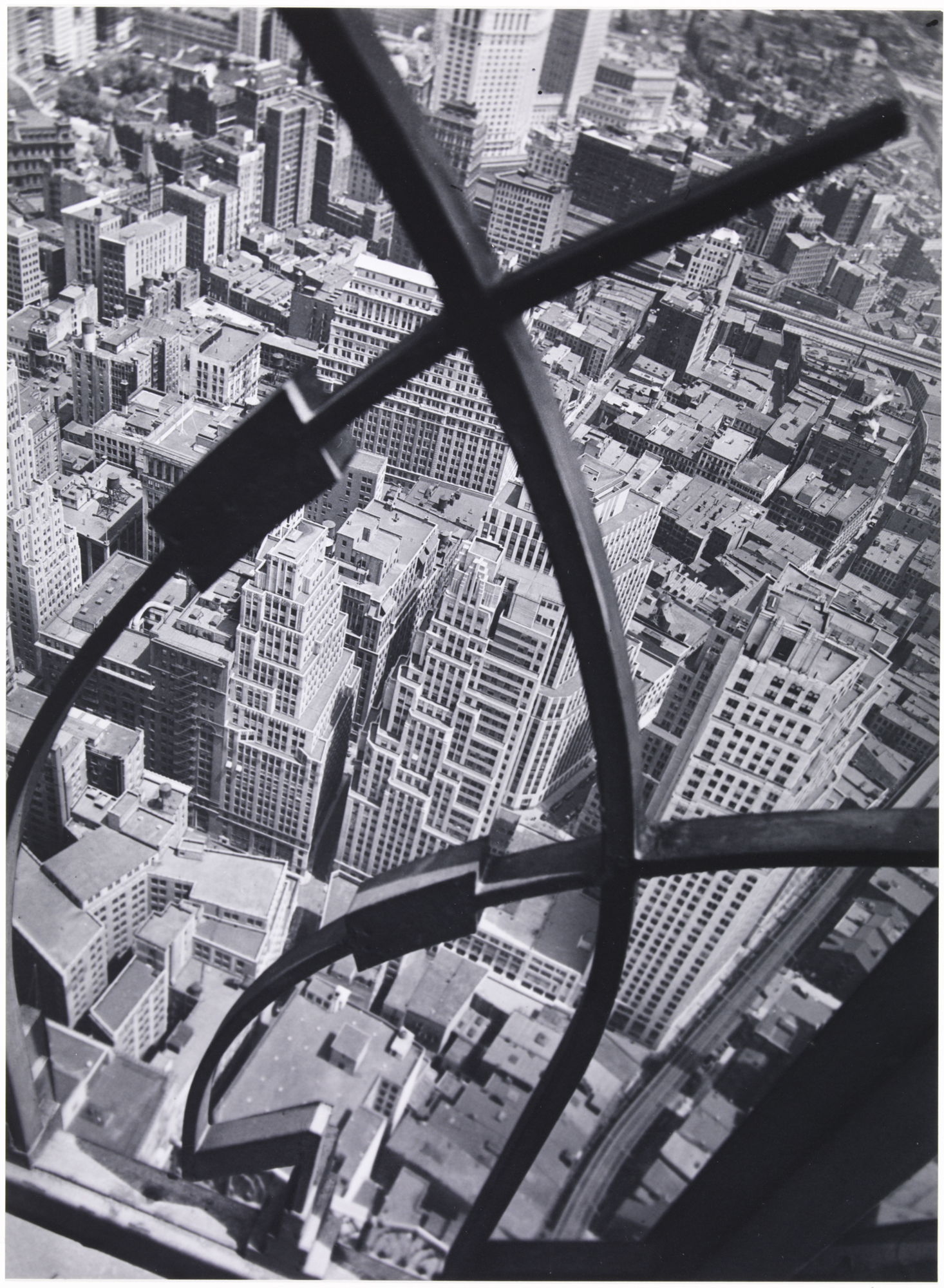

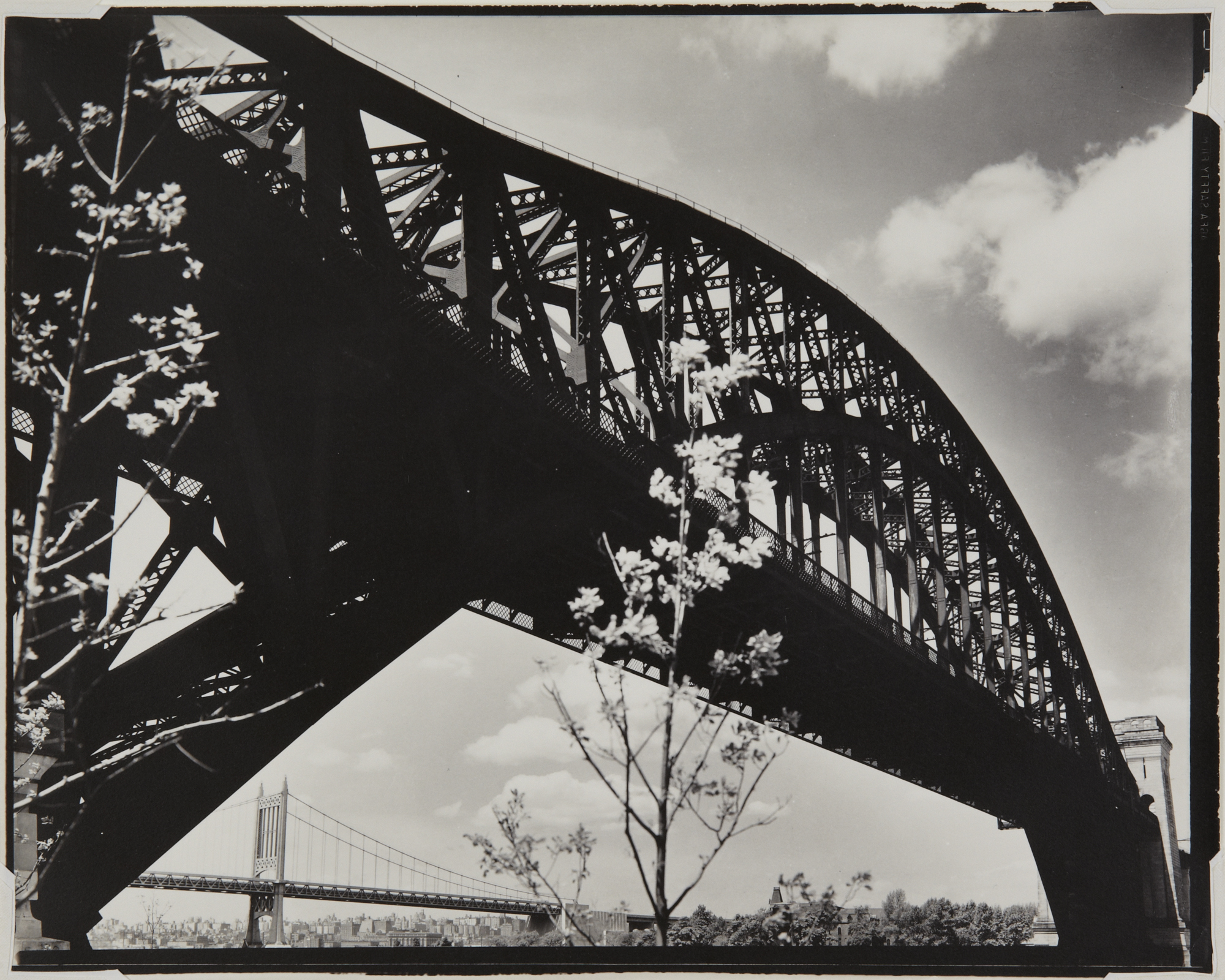

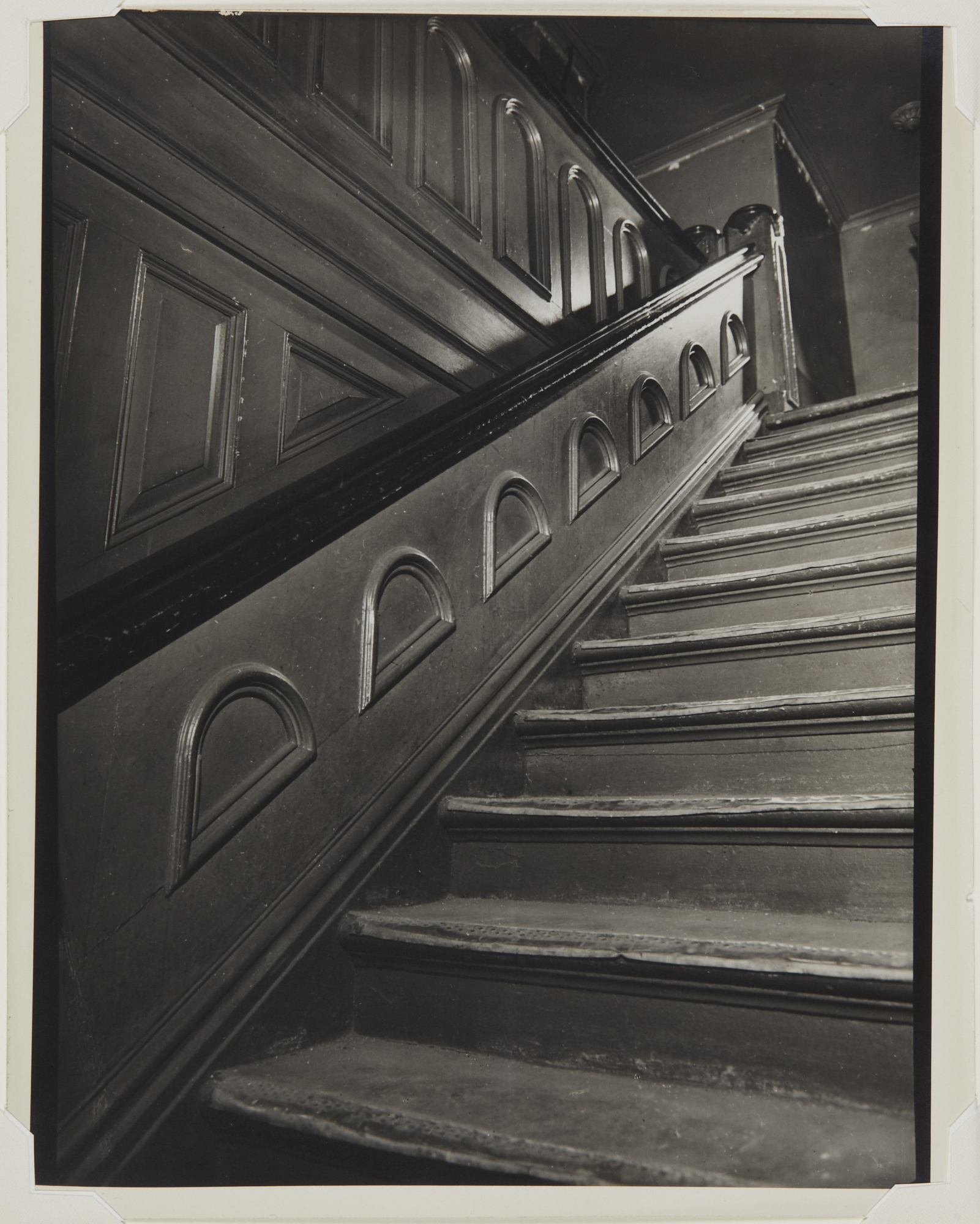

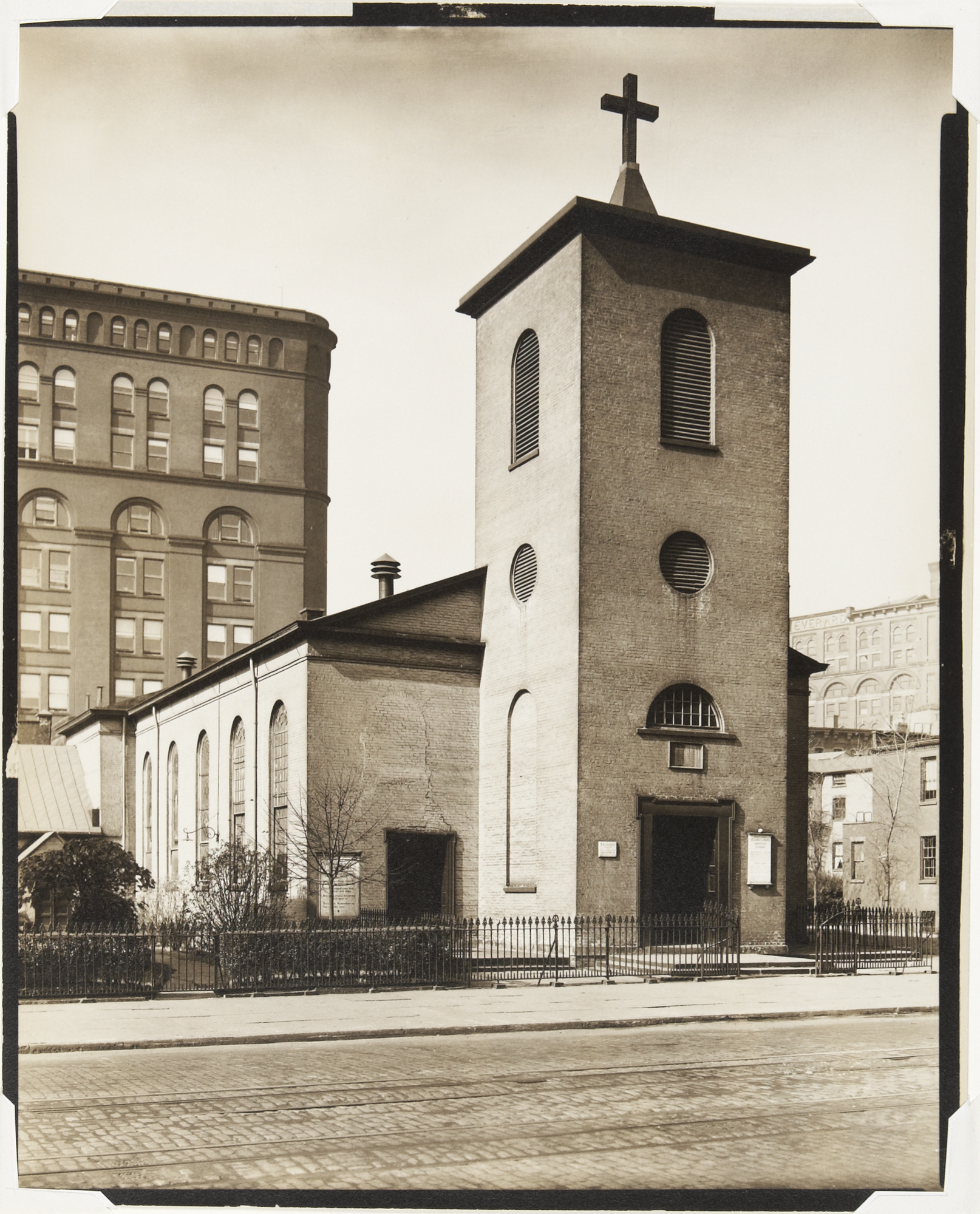

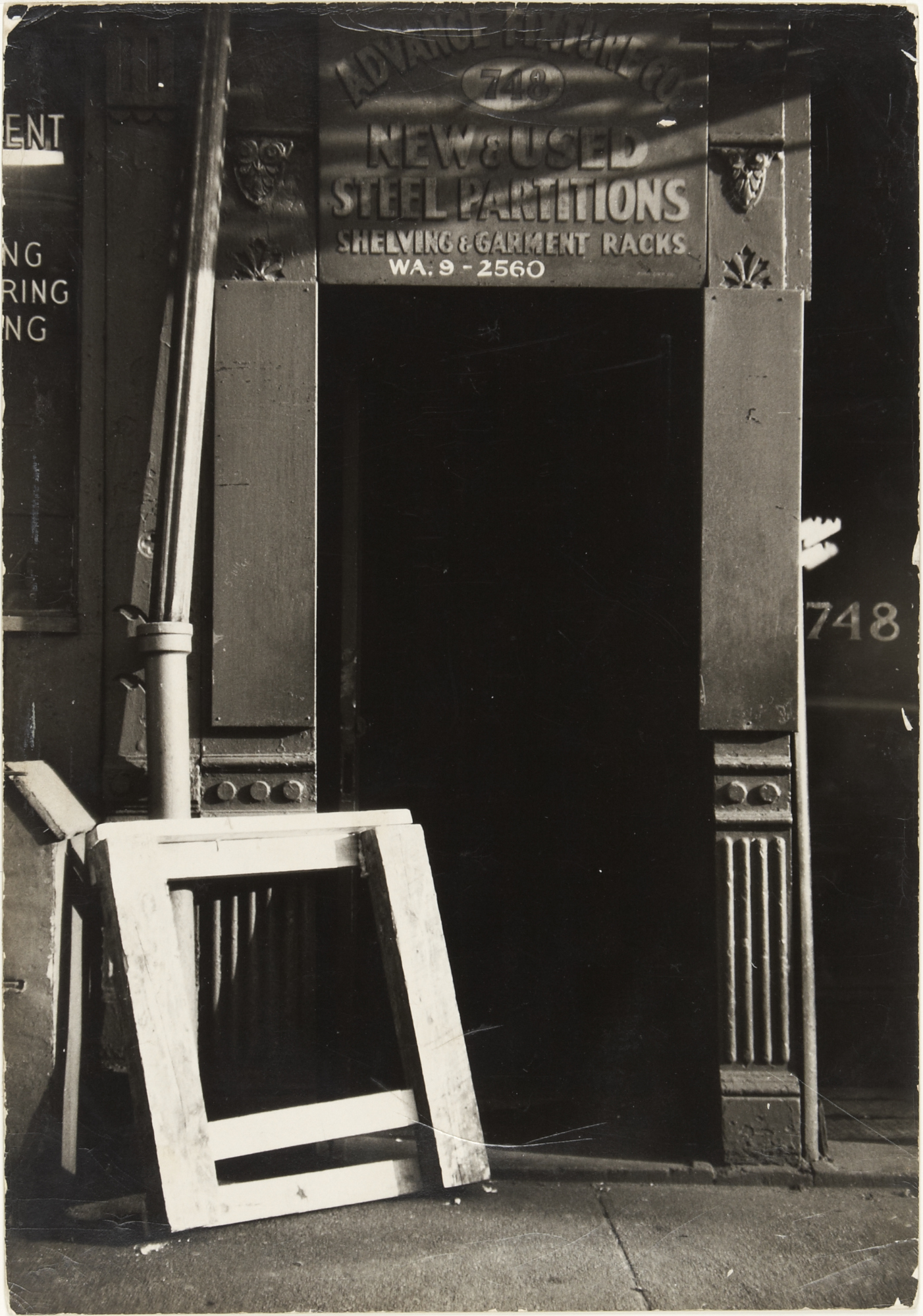

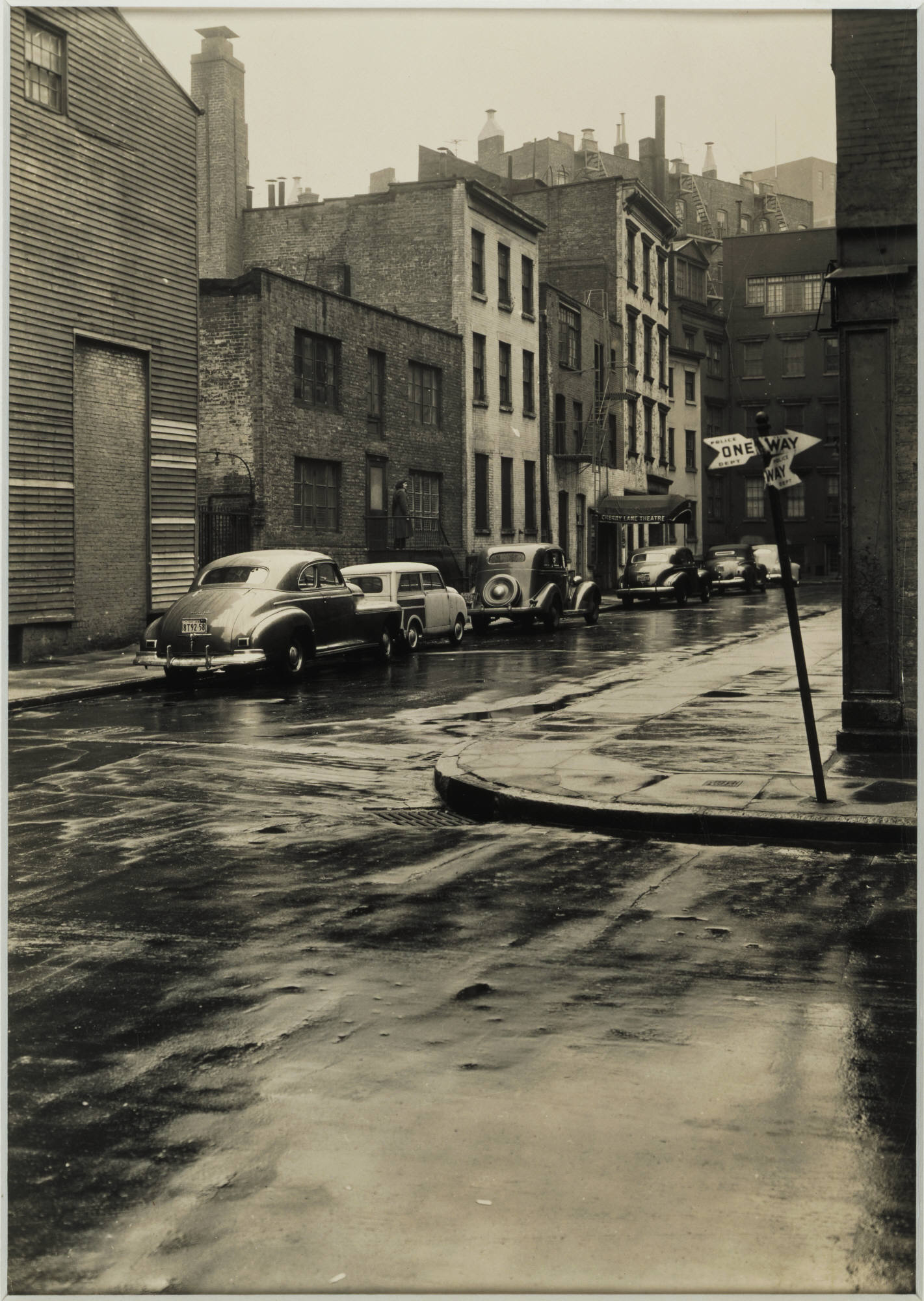

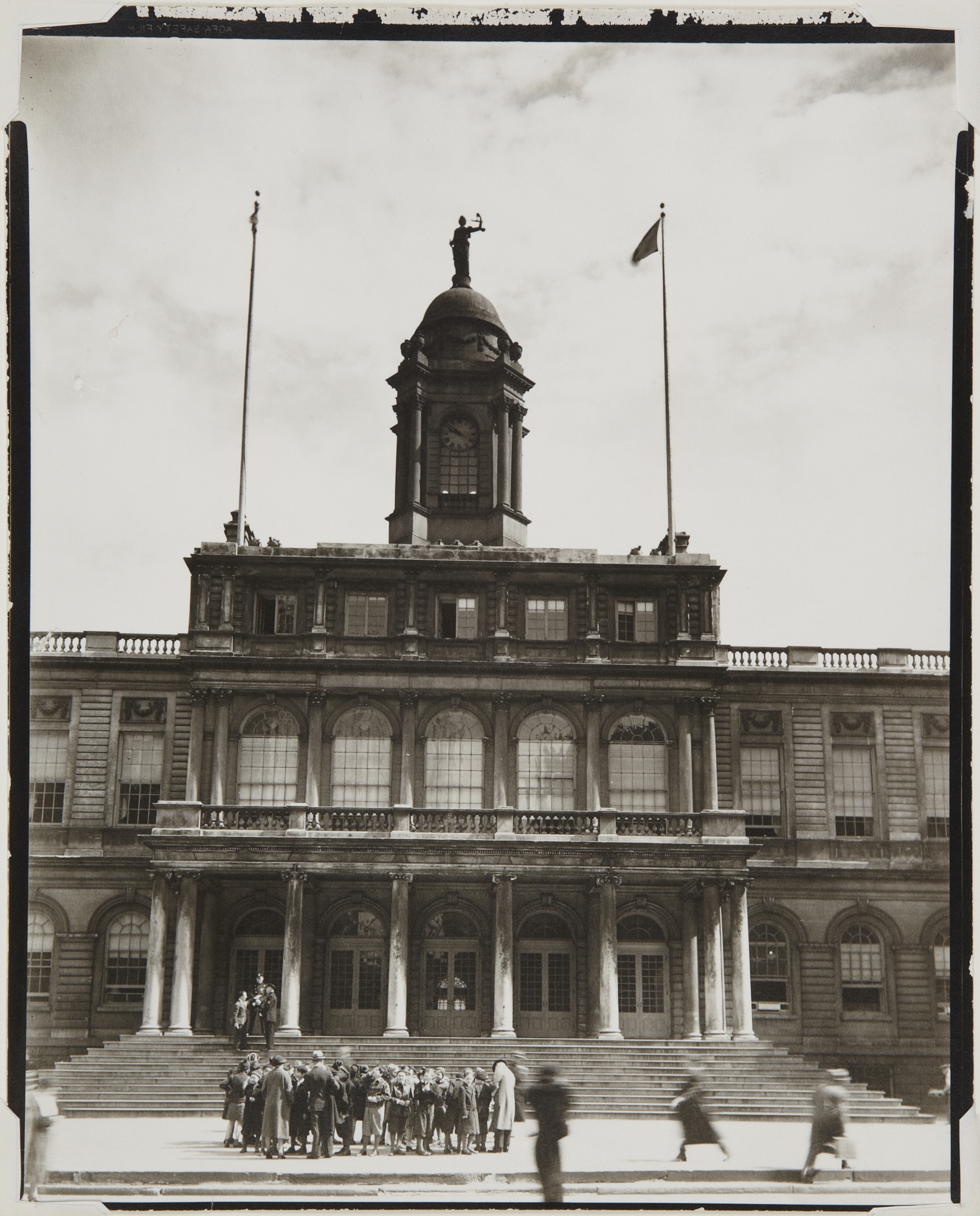

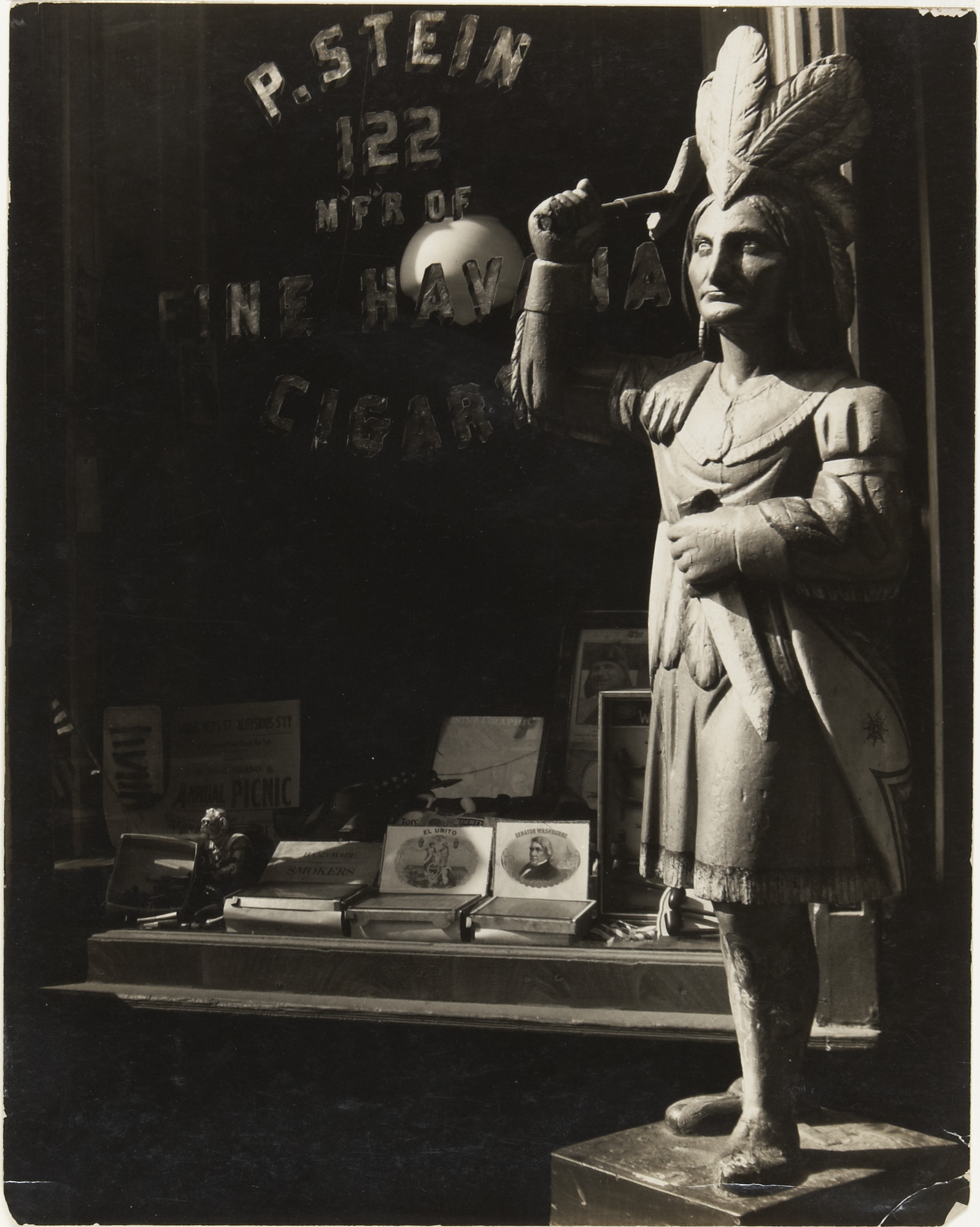

Fascinated by New York City and the changes that had occurred in it during her absence, she began the monumental work of documenting its visual presence—its sweeping technological innovations, its bridges, its canyonlike streets overtowered by skyscrapers (many of the most famous under construction at that time), its nineteenth-century brownstones and even earlier vestiges of colonial architecture, its littered streets, its hum and vitality, its sparkling transformation at night into a fairyland of light and glitter. The rest is history. The right artist and the right project—one demanding perseverance, vitality, and great individuality of imagination—had met. Her efforts were finally rewarded in 1935 when the New Deal's Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration agreed to sponsor her documentation of New York under the project title "Changing New York." The book of the same title, published in 1939, was a milestone in the history of photography.

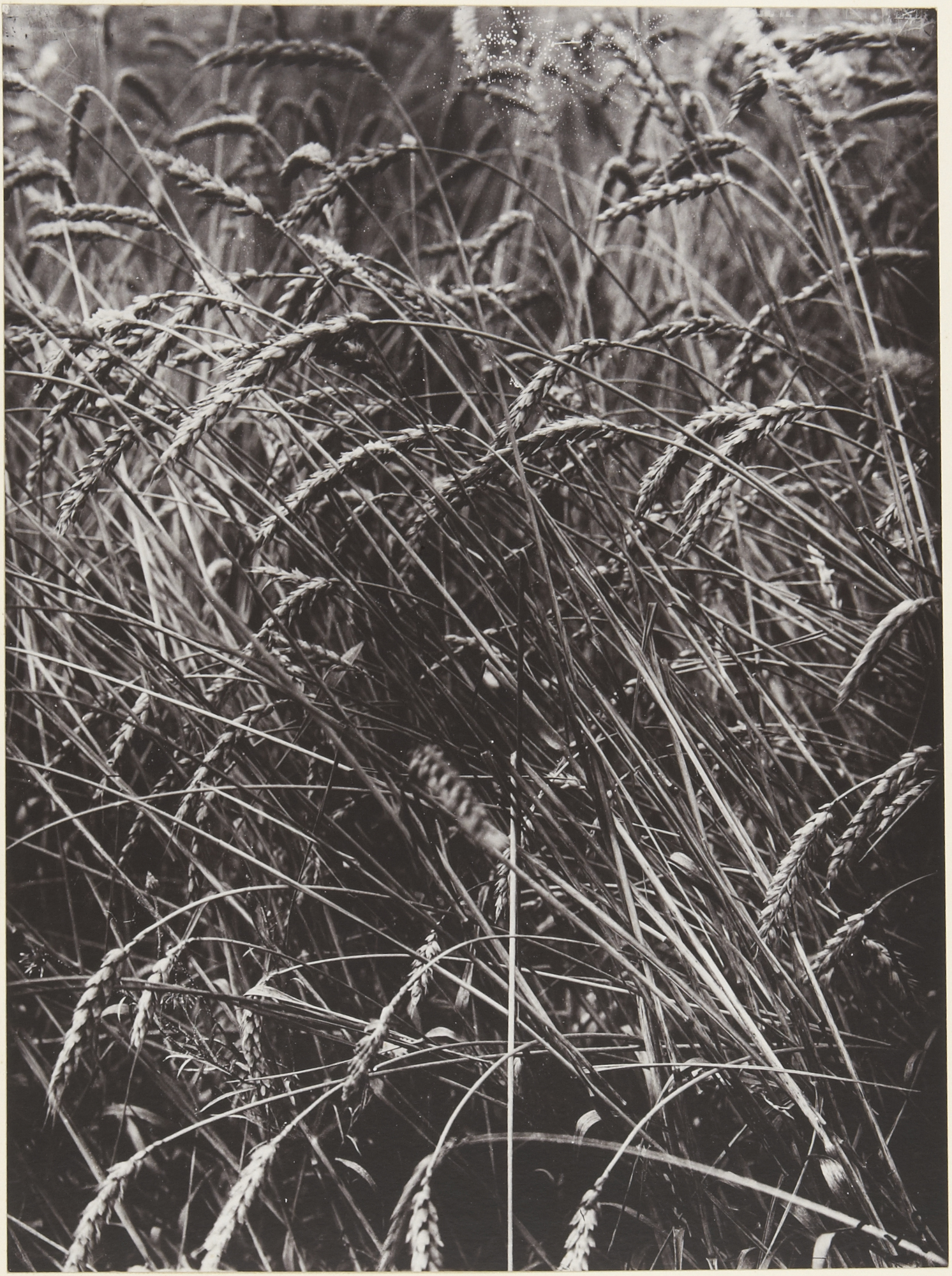

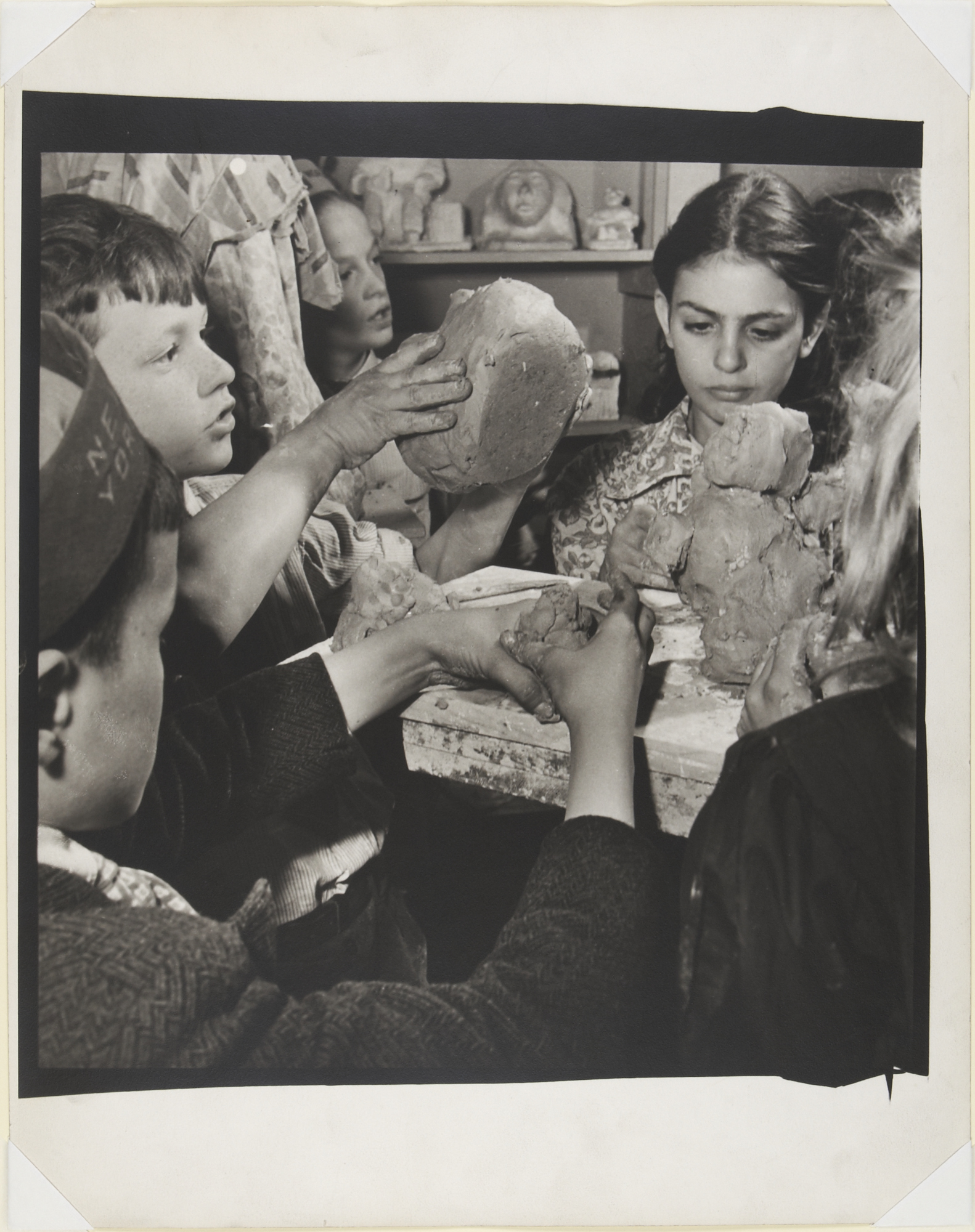

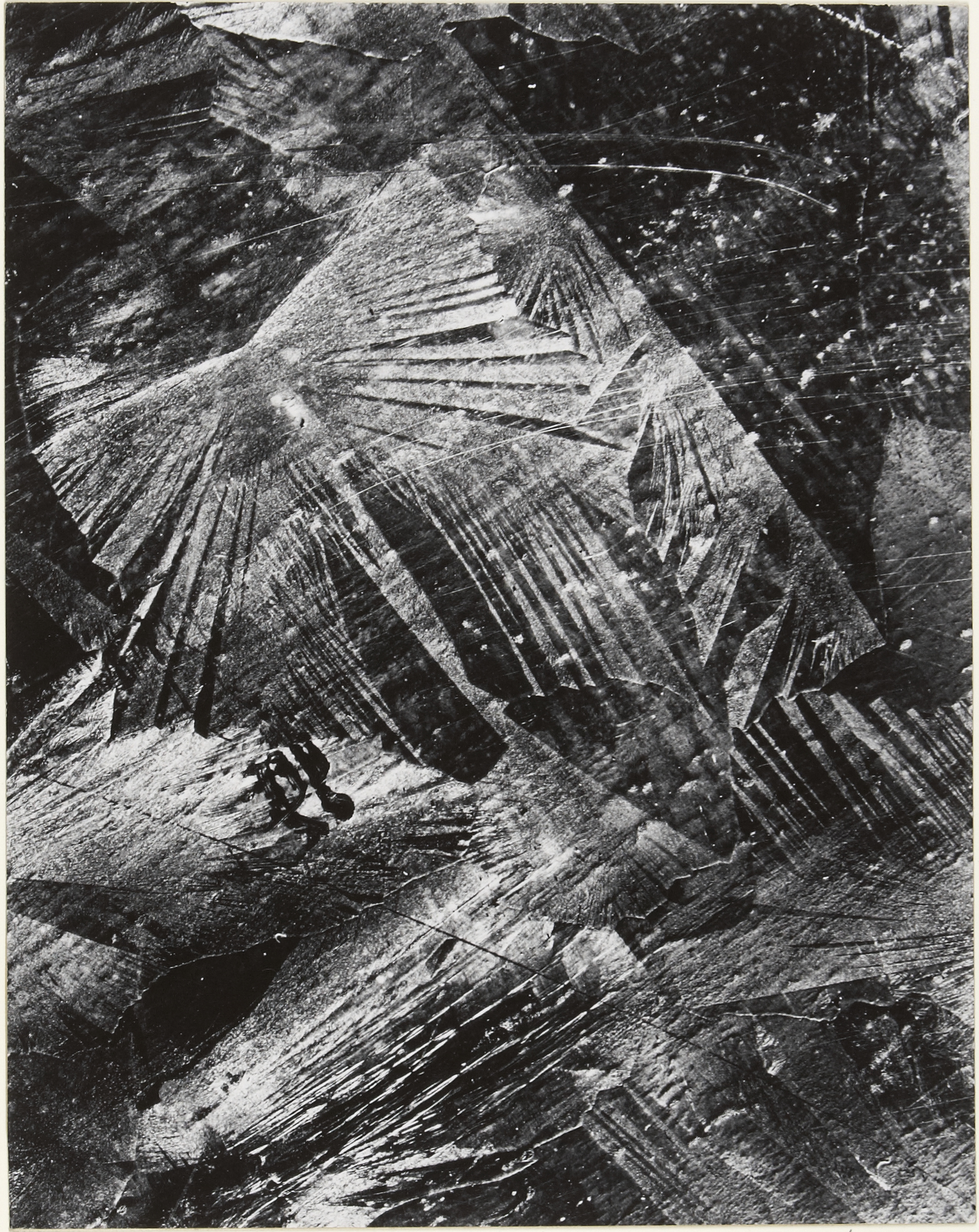

Since 1939 Abbott has engaged in many projects, turning her attention to the photography of scientific phenomena and working for the Physical Science Study Committee at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She now lives in rural Maine, where she moved in 1962. She continues to be outspoken in her comments concerning photography which she believes is the most important art form of our time. "It took the modern period to develop an art based on scientific sources, on chemistry and optics. The vision of the twentieth century has been created by photography." (5)

As for realism and the mechanistic aspect of photography, her own summing up of her experience with a camera presents a powerful, lucid argument for the creativity of the photographer and also provides insights into our responses to her photographs:

"By the choice of subject and the special treatment given a subject, [the photograph] is as personal as writing or music; while by the fact that it works with an instrument to record a segment of reality given and already made … it is impersonal, to the highest degree." (6)

Abbott also believes that "while significant reality is the subject matter of the photographer, it follows that … the choice of subject is inescapably a subjective one. One cannot help equating the objective world with oneself." (7)

We, too, read ourselves into her photographs, experiencing the New York of the 1980s more fully and acutely by savoring her images of the 1930s. Her photographs of both the twenties and the thirties provide us with more than a souvenir, more than a record or document. By an act of creative imagination Berenice Abbott has revealed to us something of the indestructible essence of a place or a time that resists oblivion and change. For many of us, this creative act seems both life-enhancing and revitalizing.

1. Conversation with Berenice Abbott, February 25, 1982. During the conversation the artist discussed her remarks published in Alice C. Steinbach, "Berenice Abbott's Point of View," an interview with Berenice Abbott, Art in America (November–December 1970): 77–81.

2. Conversation with Berenice Abbott, February 25, 1982. During the conversation the artist discussed her remarks published in Alice C. Steinbach, "Berenice Abbott's Point of View," an interview with Berenice Abbott, Art in America (November–December 1970): 79.

3. Berenice Abbott, "What the Camera and I See," Art News (September 1951): 36.

4. Conversation with Berenice Abbott, February 25,1982. See also Art in America (November–December 1970): 77–81

5. Avis Berman, "The Unflinching Eye of Berenice Abbott," Art News (January 1981): 87.

6. Art News (September 1951): 30–37.

7. Conversation with Berenice Abbott, February 25, 1982. The same idea was also expressed in Art News (September 1951): 36–37.

Barbara Shissler Nosanow Berenice Abbott: The 20s and the 30s (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press for the National Museum of American Art, 1982)

Objects at Yale Center for British Art (1)

Objects at Archives of American Art (16)