Irving Penn

The conjunction between art and commerce that winds through Penn's career challenges our usual definitions of both these areas. Issues of art—the pursuit of a particular aesthetic standard—and advertising—the creation of desire—are topics usually considered antithetical. Concerned with both, for almost half a century [Irving] Penn has fashioned his career along complex and occasionally mysterious lines.

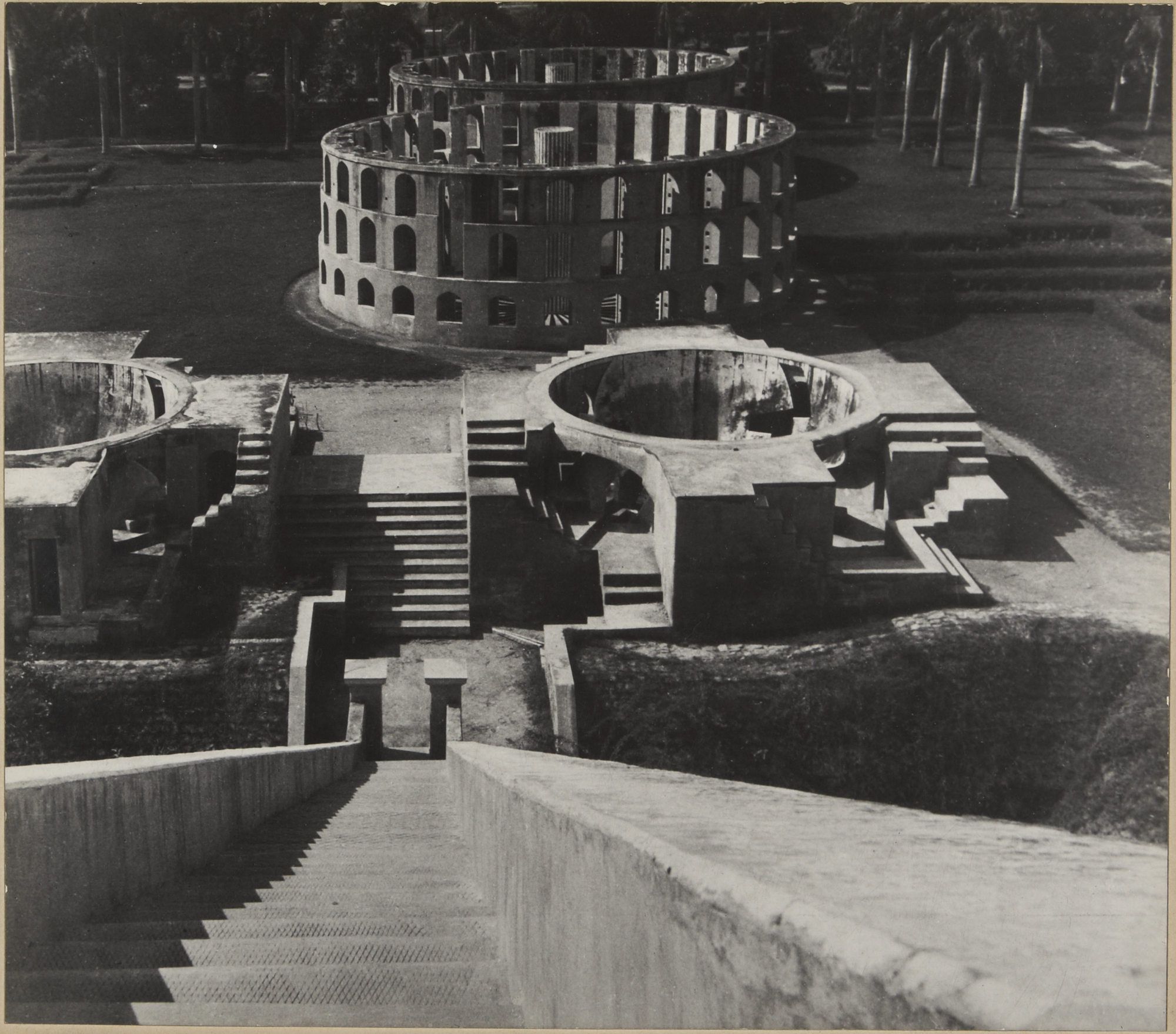

Penn's photography is best known through magazines; his first photographs were for the printed page, not the photographic print. Through the influence and resources of his sponsors—after 1943 predominately Condé Nast—he has made portraits of some of this century's most important artists and has photographed the most beautiful women dressed by the most distinctive couturiers. They have also made possible photographic excursions to places such as Morocco, Peru, and New Guinea, remote from fashion capitals. His still-life arrangements of geometric purity or reclaimed trash were posed in a studio furnished with lights and backdrops that might also have accommodated the demands of a well-organized advertisement for perfume or cosmetics. The interconnections between art and advertising in Penn's work are understandable. How he manages to simultaneously accomplish so much is remarkable; that he weaves with grace and confidence the private thread of personal vision through such enormous range is his rare talent.

By his own account, [Irving Penn] drifted into the New York commercial art world almost by accident after his design studies at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art, doing graphic work for his former teacher, an ex-Imperial Russian cavalryman, Alexey Brodovitch, at Harper's Bazaar during the late 1930s. After a short stint as the advertising manager for Saks Fifth Avenue in 1940, a job he inherited from Brodovitch, he retired to Mexico for a year of painting.

In 1943, art director Alexander Liberman lured him to Vogue as his assistant. There he learned to use an 8 x 10-inch camera and published his first color image on the magazine cover. Penn demonstrated an ability to create pictorial images that could also communicate an appropriate sense of the product being sold. During his connection with Vogue and Liberman, who would become employer, patron, and collaborator, Penn coaxed a photographic style as strong and personal as a painting style from a medium whose natural tendency is to obscure and dilute the imprint of the photographer. …

As if some perfect blend of portrait and still life, Penn's fashion photographs proved to be his earliest success. Penn gave his models a kind of character that seemed bound to ideal form, and directed their arrangement with a minimum of ostentation in metaphoric designs. Without doubt, Penn's interpretations of the couturier's art were different from earlier representations of fashion. The revolutionary series of photographs that Penn made of the 1950 Paris collections for Vogue simply but emphatically revised the terms on which future fashion photographs would be considered. …

Rejecting elaborate settings for fashion, Penn instead placed his models against plain backdrops, destroying any sense of space or scale, leaving the subject of fashion to speak for itself. Penn, now in tune with the new American abstract painters—by 1950 Vogue had illustrated work by both Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko—sought to isolate his subjects from cultural associations of the prewar years. In his photographs the effect of natural light gave a reality to spare and artificial situations; light delineated every seam of a dress, and the texture of the cloth and the outline of the garments became paramount. A gesture with a long black glove might choreograph and define the space across a page. …

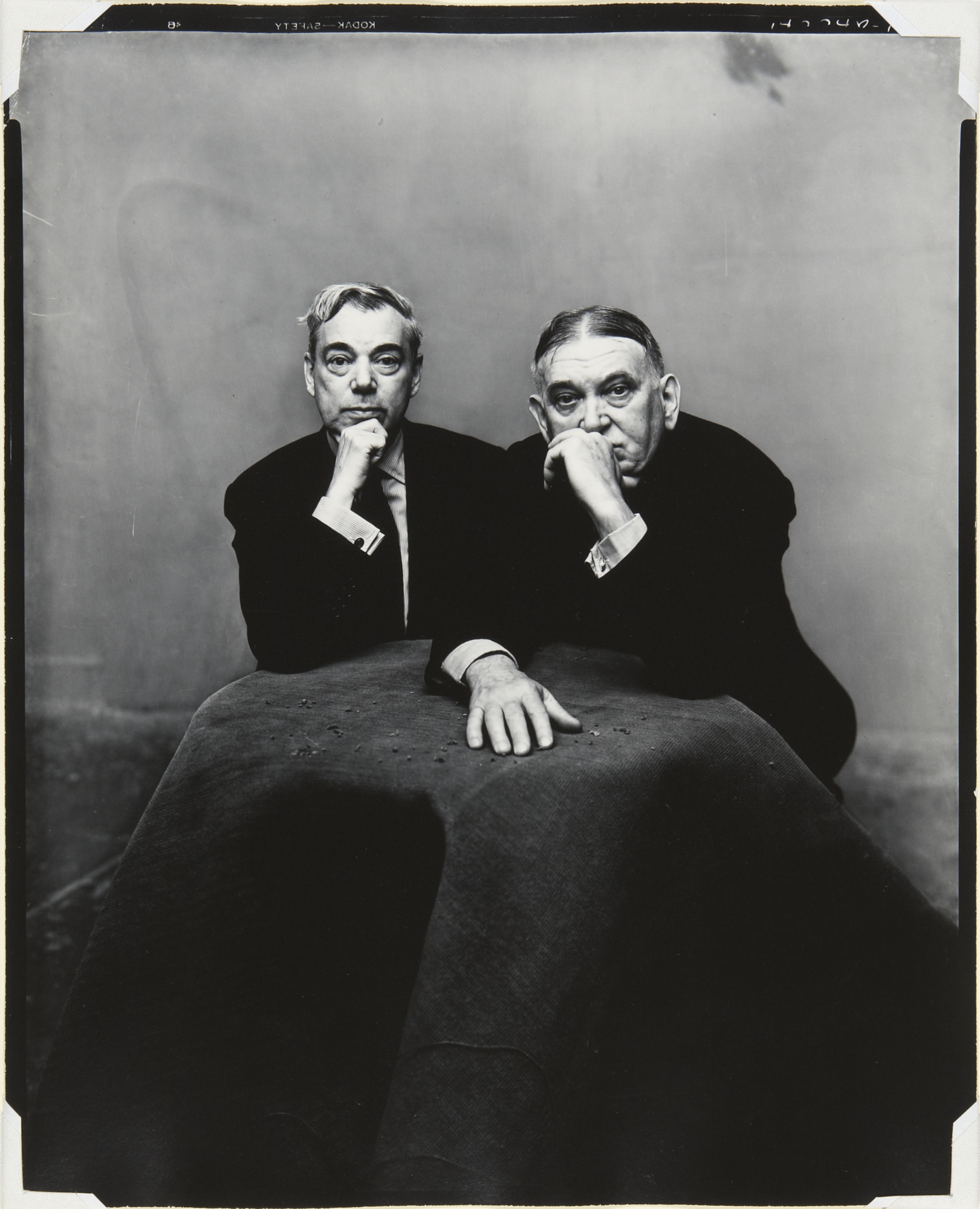

Just as his fashion photographs are more often like portraits than descriptions of the latest styles, his portraits of the period strip away all the contingency and commonplaces of experience to present the individual style of personality. Working for Vogue, first in New York and then in Europe, in the late 1940s Penn was able to photograph many members of the aging or exiled radical artistic and intellectual elite. Those who had survived the war in Europe were less known, but no less intriguing, to an eager American audience in search of cultural identity. Salvador Dali, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, André Derain, Pablo Picasso: dashing and exotic, they provided the right mix of stylish creativity appealing to a fashionable audience. The details that Penn provides for them in his images—electrical cables, the edges of the seamless backdrops, the mysterious substantiality of northern light—serve as metaphors of the necessarily spare ateliers of the artistic homeless.

Merry A. Foresta and William F. Stapp Irving Penn: Master Images, The Collections of the National Museum of American Art and the National Portrait Gallery (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990

Objects at Archives of American Art (1)

Objects at Princeton University Art Museum (8)

Objects at National Portrait Gallery (73)