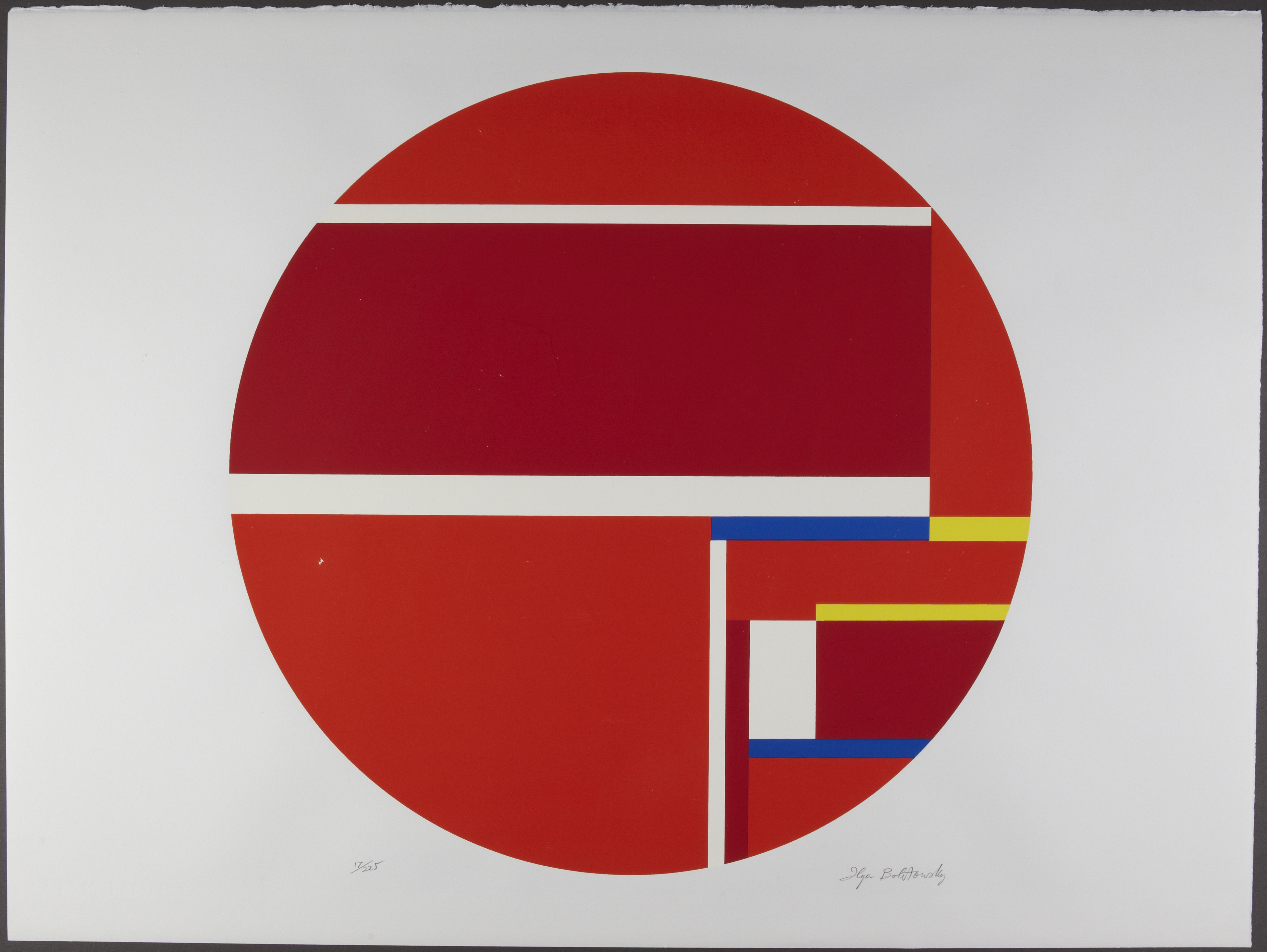

Ilya Bolotowsky

Ilya Bolotowsky was not only a founding member of the American Abstract Artists, but also one of the forces behind its programs and exhibitions. A Russian immigrant to New York in 1923, Bolotowsky studied at the National Academy of Design between 1924 and 1930. He then worked for several years as a textile designer and taught art in settlement houses. By 1932, he had saved enough money so that, combined with a small scholarship, he was able to spend ten months in Europe, primarily Italy, Germany, Denmark, and England, with a few weeks in Paris. When he left for Europe, Bolotowsky was already familiar with Picasso, Matisse, other avant-garde Parisian painters, and Russian Constructivists. He appreciated Cubism because it shattered naturalism.(1) Yet, his work in Europe was more akin to the Expressionism of Chaim Soutine, which he knew through his friend William H. Johnson, another Soutine aficionado.(2)

Bolotowsky again did textile designing on his return to New York. In 1934, he worked for the Public Works of Art Project, a pilot program of federal support that paved the way for the WPA-FAP in 1935. When Gertrude Greene mentioned that Burgoyne Diller was heading up a WPA mural project that would use abstract artists, Bolotowsky submitted sketches. Diller arranged Bolotowsky's transfer from the WPA teaching project, and Bolotowsky set to work on a mural design for the Williamsburg Housing Project, whose architect, William Lescaze, was sympathetic to abstraction.

In his abstract compositions of the mid 1930s, Bolotowsky gave free rein to a variety of stylistic approaches. He encountered the work of both Miró and Mondrian in 1933, and by 1936 introduced a Mondrianesque grid pattern as the framework for playful biomorphic forms and rectangular planes of unmodulated color. His flirtation with Miró is apparent in the lyric dancing of simple geometric shapes, organic forms, and thin, directional lines over the surface of a mural study he completed for the Hall of Medical Science in the Health Building at the 1939 New York World's Fair.

During World War II, Bolotowsky served in the Army Air Corps. After his discharge, he replaced Josef Albers for two years at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. From 1948 to 1957 he taught at the University of Wyoming and at Brooklyn College; from 1957 to 1965 he was Professor of Art at State Teacher's College in New Paltz, New York, and from 1965 until 1971 he taught at the University of Wisconsin in Whitewater. At various times he also held short-term or adjunct positions at Hunter College in New York, the University of New Mexico, and Queens College.

During the 1940s, Bolotowsky began looking more closely at the purist geometries of his friends Burgoyne Diller and Albert Swinden, and especially at Mondrian's Neo-plastic paintings. His own work underwent a purification of bothform and color.(3) He did not immediately reduce his palette to the primary colors, as well as black and white, as did the Dutch painter, nor did he focus exclusively on rectangular geometric configurations. In paintings such as Architectural Variation of 1949, Bolotowsky exorcised all suggestions of illusionistic space. He described his work during the forties in terms of surface tensions:

"In the early forties I still used diagonals. A diagonal, of course, creates ambivalent depth diagonal depth might go either back or forth. It's not like perspective which goes only one way. … I had to give up diagonals because the space going back and forth was becoming too violent. The diagonal space was getting in the way of the tension on the flat surface. You cannot get an absolute flatness in painting because of the interplay of the colors, the way they feel to us. But you can achieve relative flatness, within which the colors and the proportions might push back and forth creating an extra tension. This tense flatness must not destroy the overall flat tension, which, to my mind, in two-dimensional painting is the most important thing."(4)

In Wyoming, Bolotowsky began making experimental films, usually based on either Greek myths or myths Bolotowsky fabricated. His films used actors and were not abstract. Bolotowsky believed that film was an art of empathy and that abstraction represented a conceptual approach more appropriately conveyed through painting and sculpture.(5)

Before the war, Bolotowsky had exhibited in a variety of group exhibitions, including the Museum of Modern Art's New Horizons in American Art in 1936 and in both the second and third annual shows of The Ten (1936 and 1937). In 1946, after his return, his paintings began to receive wide attention. He had solo exhibitions at J.B. Neumann's New Art Circle and at The Pinacotheca gallery, and in 1954, he joined Grace Borgenicht's gallery, where he showed biennially into the 1970s.

1. Deborah M. Rosenthal, "Ilya Bolotowsky," in John R. Lane and Susan C. Larsen, Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America, 1927–1944 (Pittsburgh, Pa.: Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute, in association with Harry N. Abrams), pp. 51–54.

2. Louise Averil Svendsen and Mimi Poser, "Interview with Ilya Bolotowsky," in Ilya Bolotowsky (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1974), p.15.

3. See Ilya Bolotowsky, "On Neoplasticism and My Own Work: A Memoir," Leonardo2, no. 3 (July 1969): 221–30; and Nancy J. Troy, Mondrian and Neo-Plasticism in America (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1979).

4. Louise Averil Svendsen and Mimi Poser, "Interview with Ilya Bolotowsky," in Ilya Bolotowsky (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1974), p.24.

5. Bolotowsky explained empathy according to Wilhelm Woninger's definition, as "the essence of any vitality, activity, anything to do with life. Brancusi's bird or fish are extreme examples of empathy. … On the other hand, a very beautiful bridge, I would say that's pure abstraction. It's not alive. It's just a perfection in structure beyond human bounds. And so that would be pure abstraction." Svendsen and Posner, "Interview," p.18.

Virginia M. Mecklenburg The Patricia and Phillip Frost Collection: American Abstraction 1930–1945 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press for the National Museum of American Art, 1989)