Roy Lichtenstein

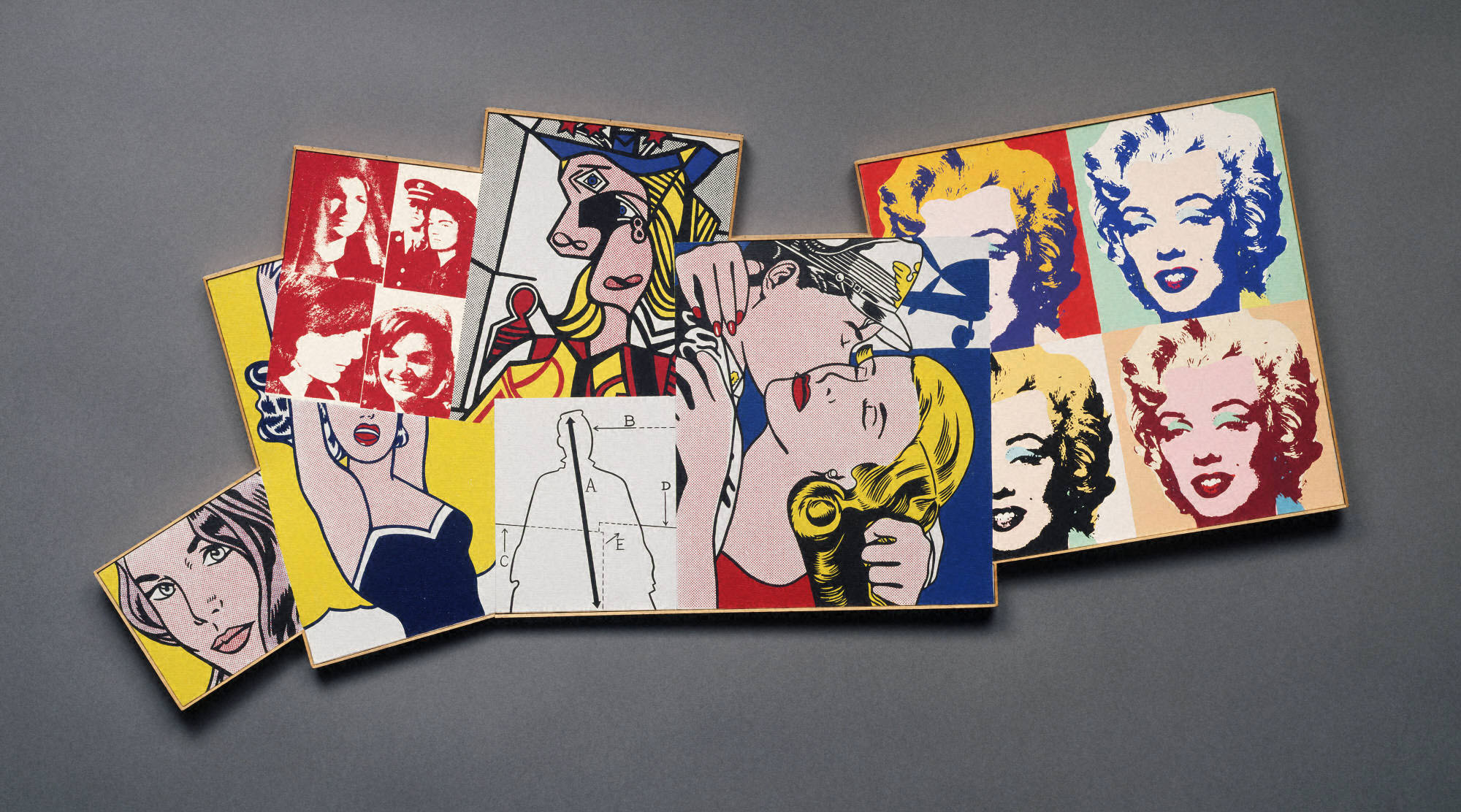

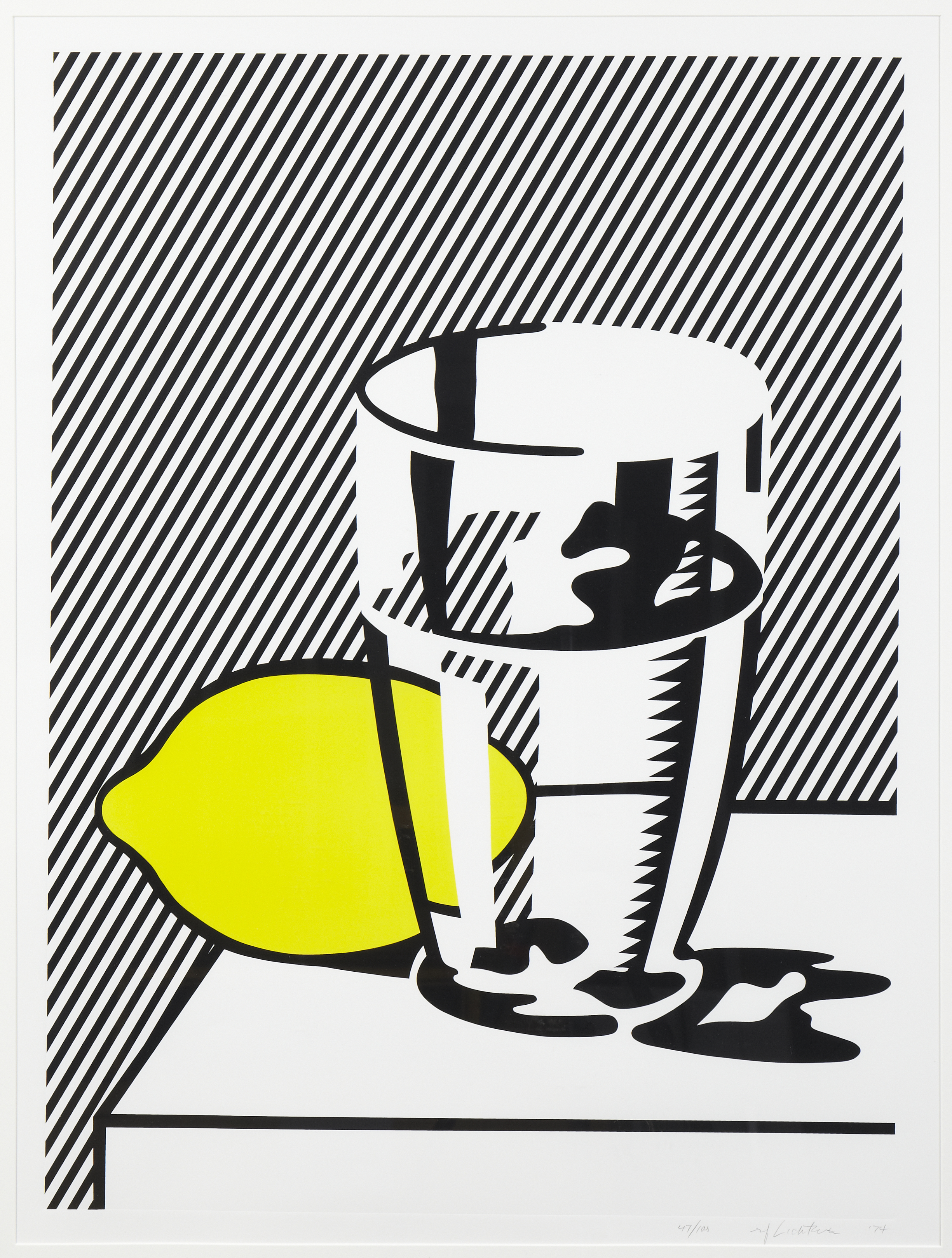

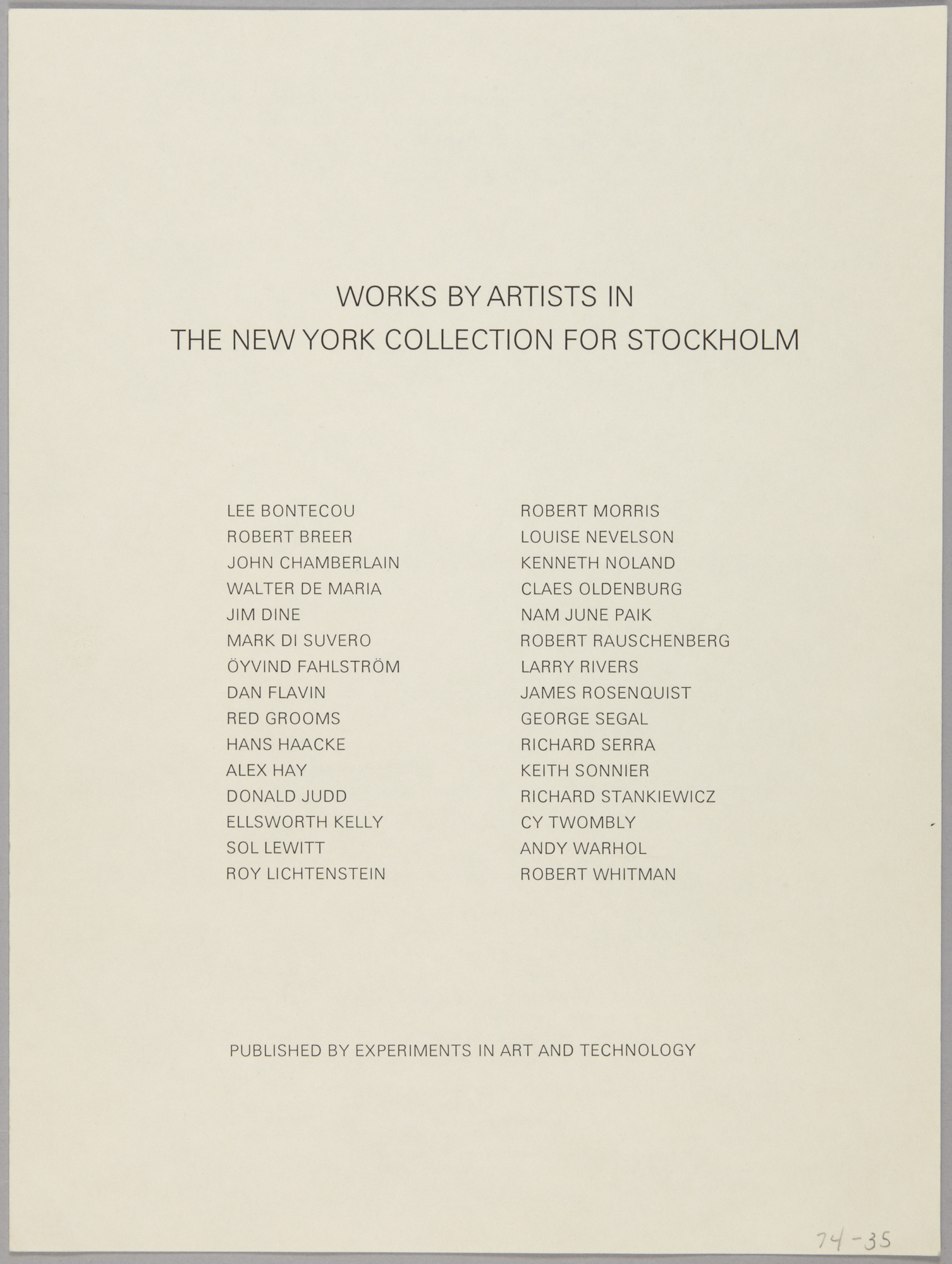

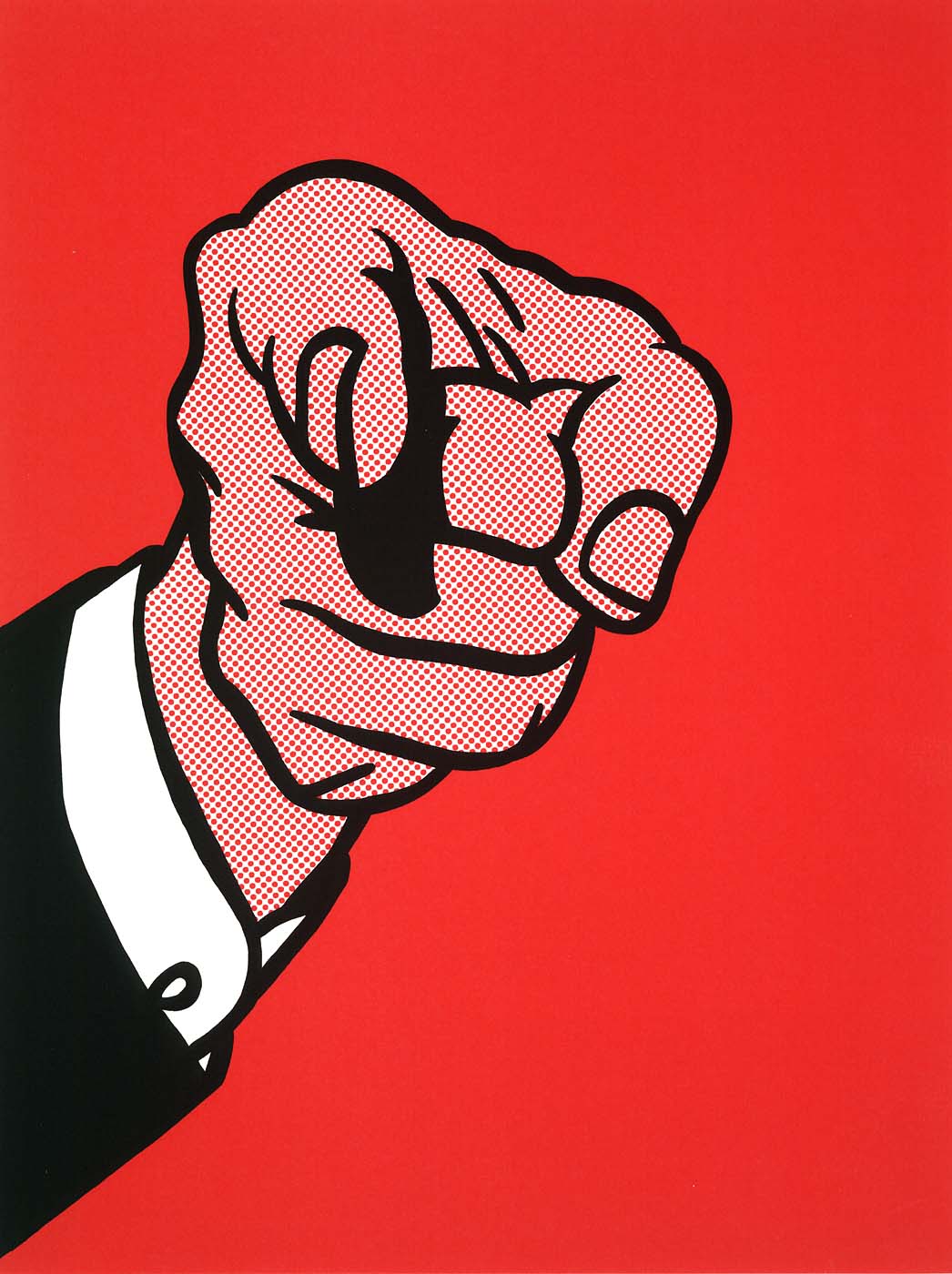

Those of us who never had the opportunity to meet Roy Lichtenstein in person probably first encountered him in the historical accounts of the 1960s. According to the now-familiar narrative of American art in the Kennedy era, he burst onto the scene in 1962 with his first one-man show at the Leo Castelli Gallery and reigned with Andy Warhol and James Rosenquist as the triumvirate of New York Pop art. Like them, he wanted his pictures "to look programmed or impersonal," reflecting the detachment of American consumer culture at that moment. Unlike them, however, he retained an ironic distance from the Pop myth. "I don't really believe I'm being impersonal when I do it" is the way he qualified it. From then on, Lichtenstein strove to make art that explored and bridged a series of contradictory positions—personal and impersonal, high and low, semiotic and existential. His work in fact synthesizes many of the dominant themes of art in the United States during this century, from concern with the common culture that characterized the American Scene painters of the 1930s to obsession with the media in the 1990s.

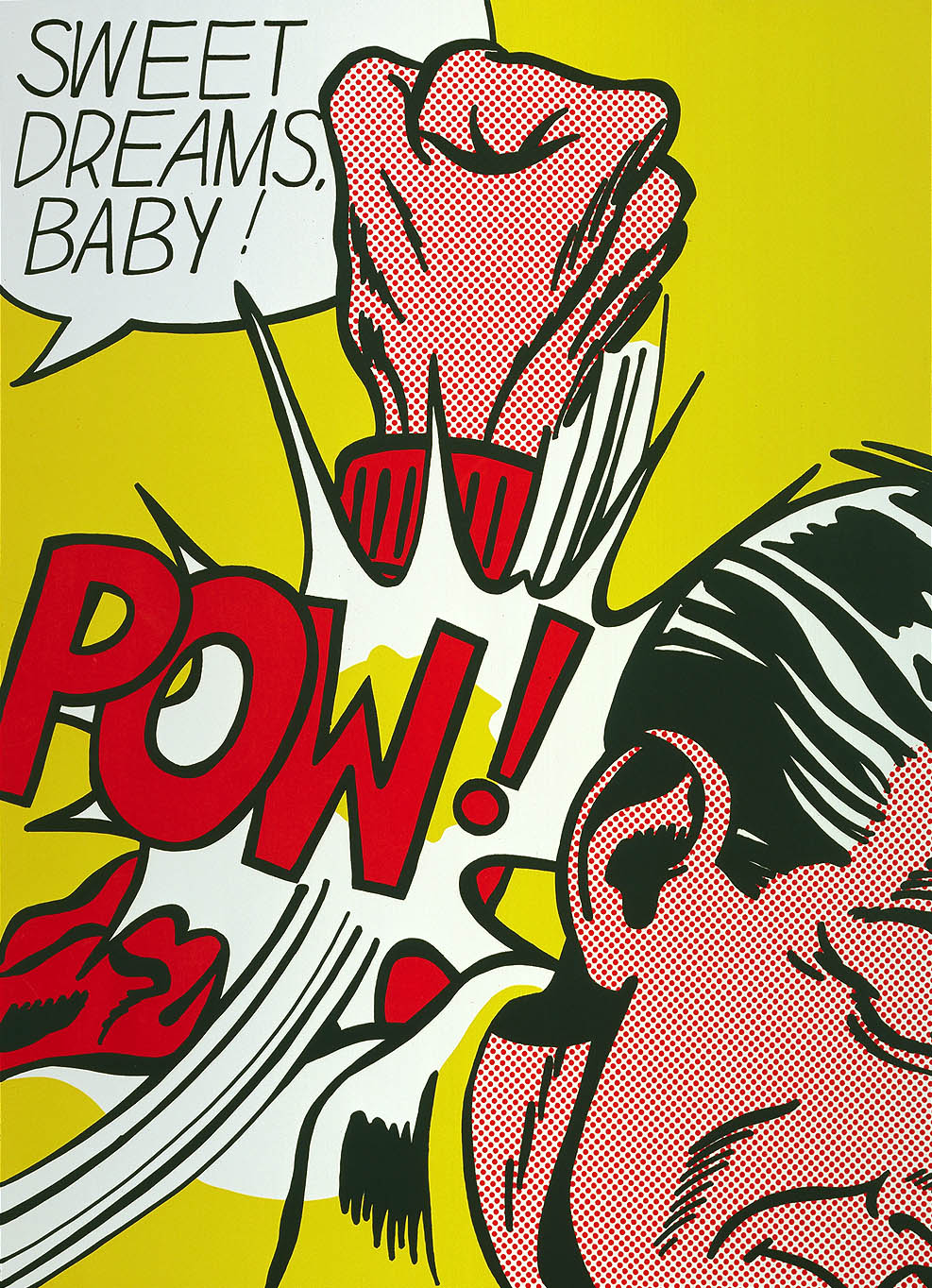

Born in 1923, Lichtenstein grew up in New York City and studied briefly with Reginald Marsh at the Art Students League, an experience that apparently left an indelible mark on his subject matter. He went away to college at Ohio State University and returned home to find a radically different art world. "I was brought up on abstract expressionism," he explained, "and its concern with forming and interaction is, I think, extremely important." This philosophy led to the pivotal moment in 1960 when he painted a Mickey Mouse embedded in an abstract expressionist matrix. In 1961, comics and advertising images emerged to fill the frames, and a few years later he rejected Mickey and Popeye for soap opera-like comics of his own design. Here, of course, the real subject is not "the drowning girl" who would "rather sink than call Brad for help" (to cite the caption from his famous painting of that title, 1963, Museum of Modern Art, New York). Rather it is the power of media's language—its ability to translate and transform.(1)

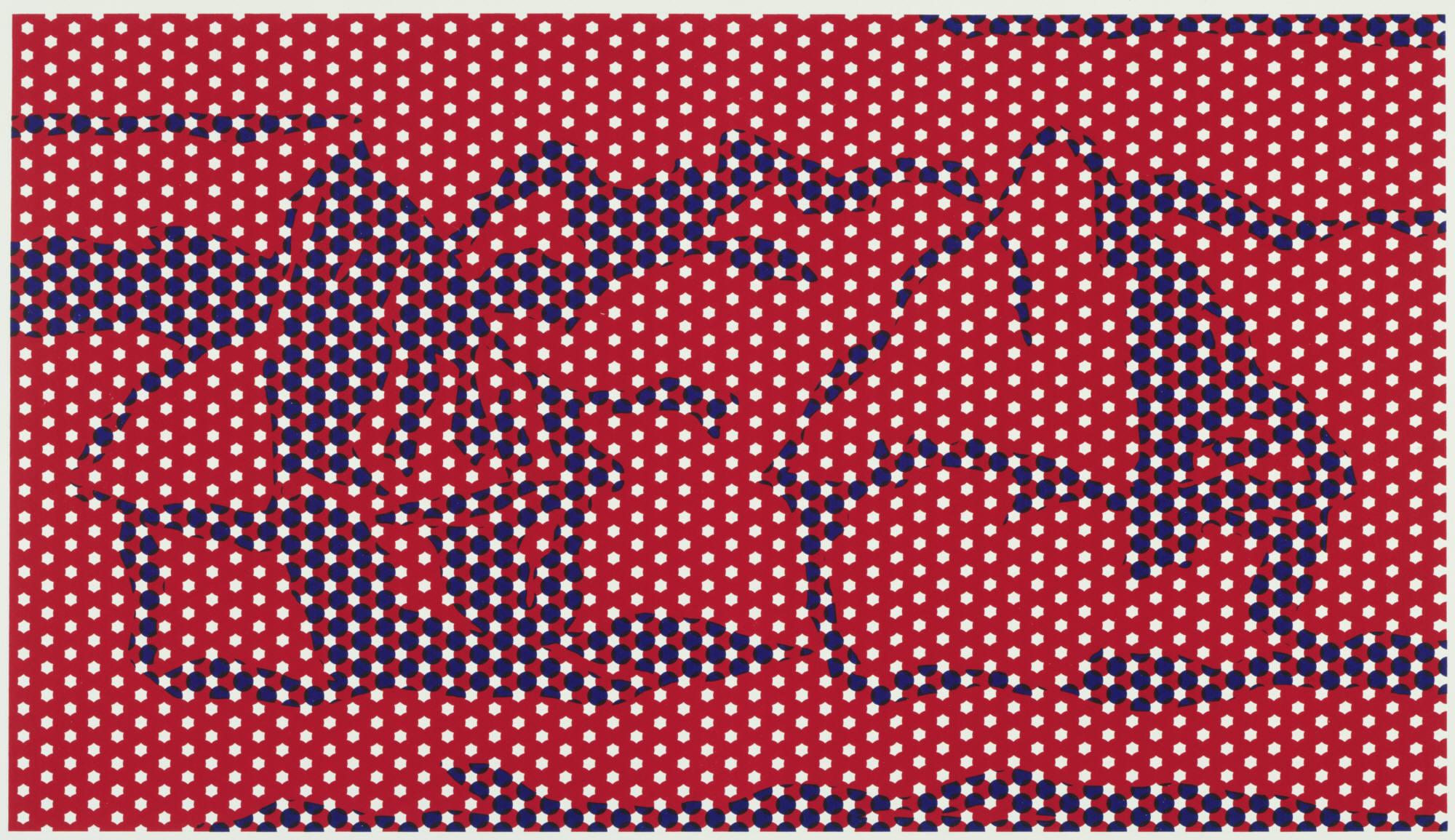

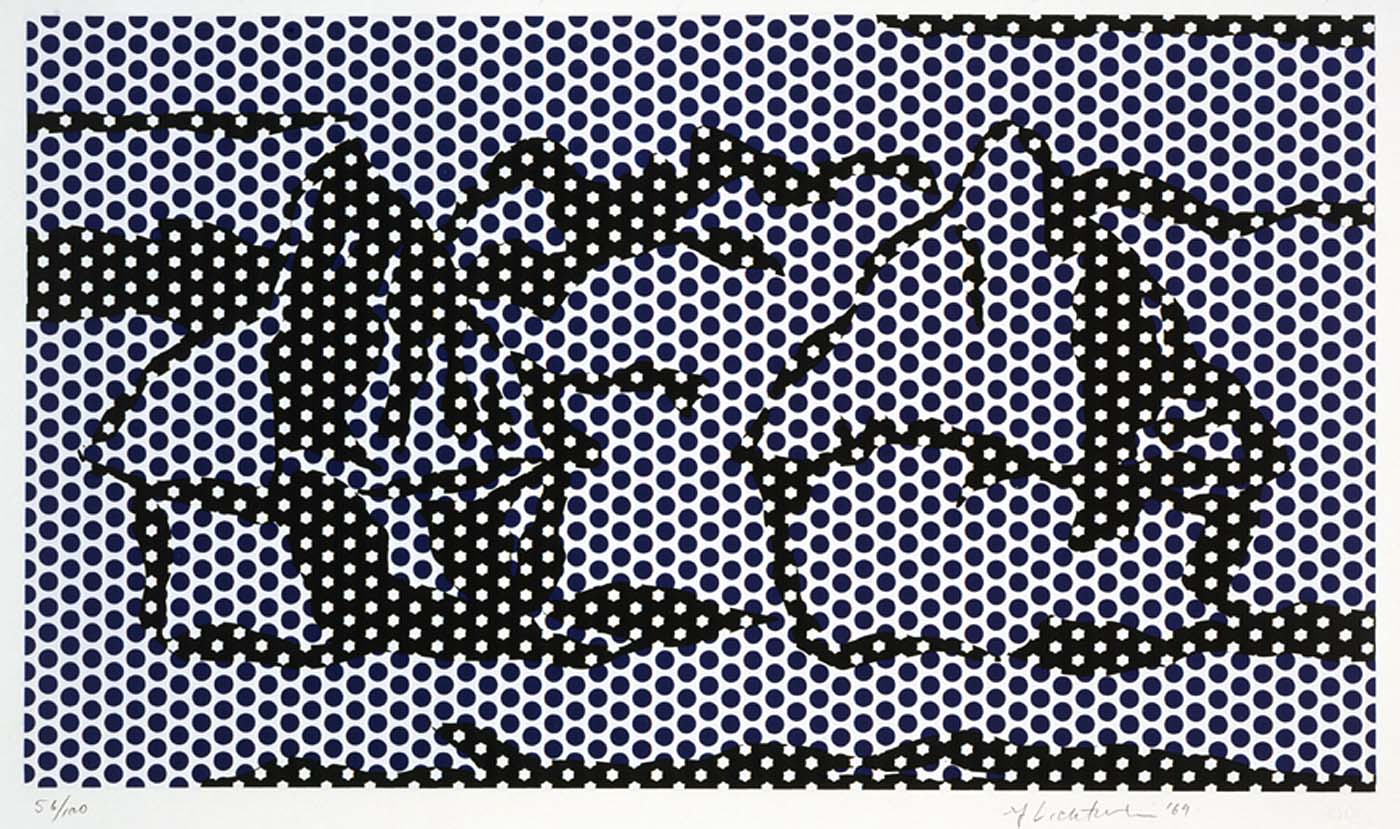

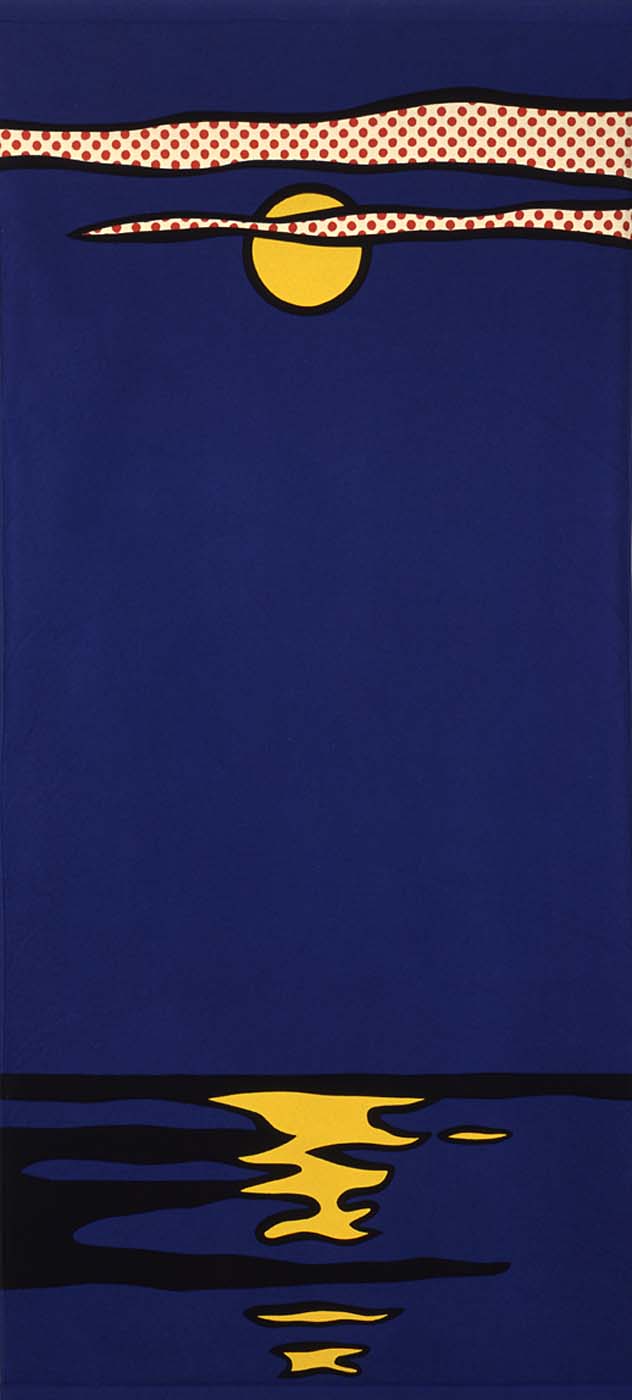

Grounded ultimately in the fine rather than the commercial arts, Lichtenstein ranged back and forth across the history of art as freely as he did across advertising and comics. In a characteristically American gesture, he felt the need to engage in an extended dialogue with the European tradition. One by one he revisited the revered figures, essaying works by Matisse and Picasso with skill and wit. Nor did he limit himself to the confines of Western art: a recent exhibition featured his refashioning of Chinese imagery rendered in the signature Ben Day dots.(2) In these works, as before, the pictorial style becomes the subject.

Roy Lichtenstein was engaged in a life-long exploration of the ways in which images speak to us. His art transcends the decade of the sixties and establishes his status as an American master of the twentieth century.

Notes

1. Quoted in Jonathan Fineberg, Art Since 1940: Strategies of Being (New York: Abrams, 1995), p. 259.

2. The exhibition entitled Roy Lichtenstein: Landscapes in the Chinese Style, was on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 19 March–6 July 1997 (there was no accompanying publication).

Katherine E. Manthorne "Appreciation: Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997), Twentieth-Century American Master." American Art journal 11, no. 3 (fall 1997), pp. 78–7

Selected Images of Roy Lichtenstein

Objects at Colby College Museum of Art (1)

Objects at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art (2)

Objects at Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields (4)

Objects at Archives of American Art (9)