Franz Kline

Born 23 May 1910, Wilkes-Barre, Pa. 1917, father committed suicide. 1919–25, attended Girard College, Philadelphia (free boarding school for fatherless boys). Family moved to Lehighton, Pa., where Kline attended high school. 1931–32, Boston University and night classes at Boston Art Students League. 1935–38, London.

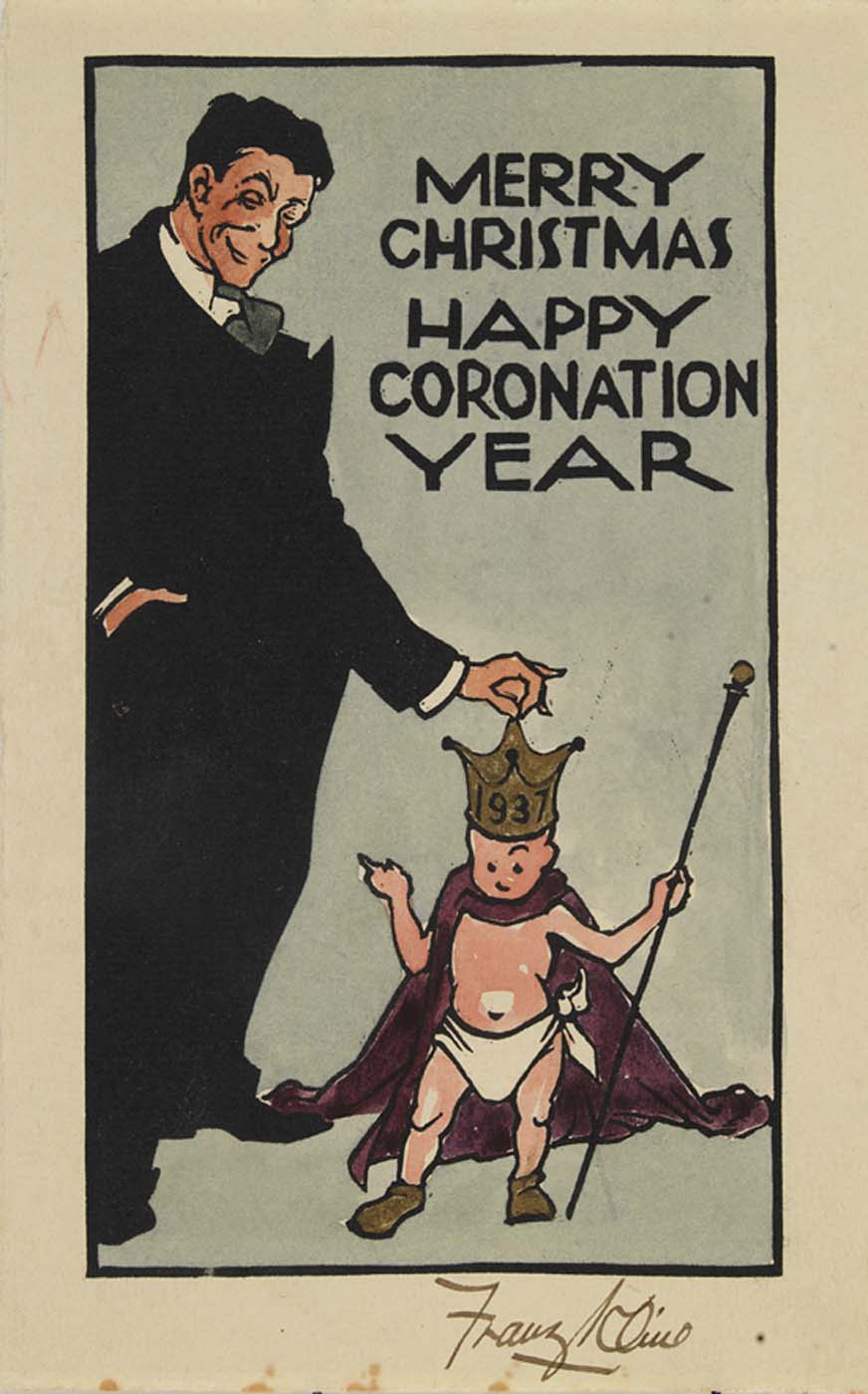

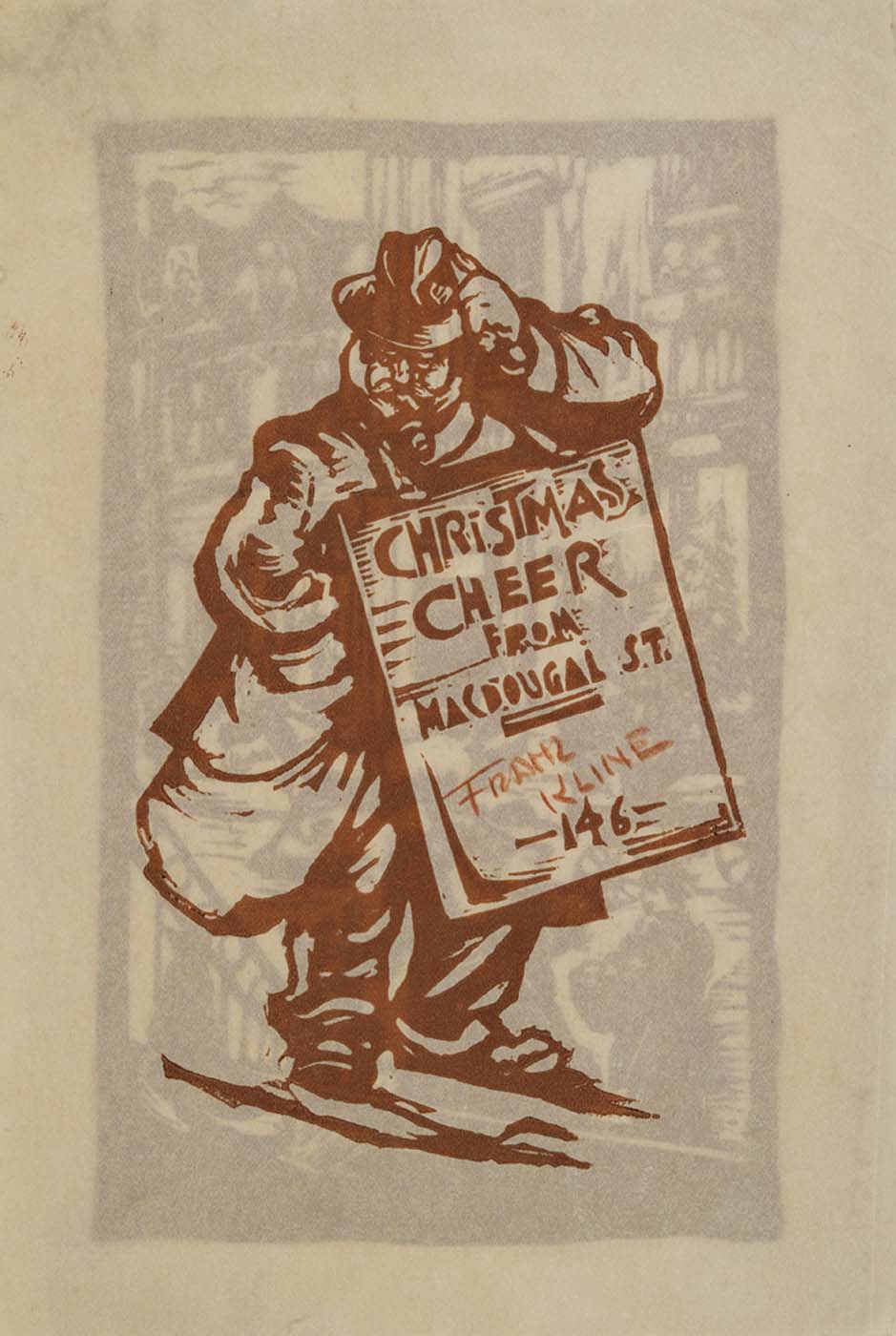

February 1938, moved to New York. Married Elizabeth V. Parsons. 1939–42, painted murals for bars. 1940–44, exhibited in Washington Square art show. 1942, exhibited in National Academy of Design's annual exhibition. 1943 and 1944, won the National Academy's annual S.J. Wallace Truman Prize.

1946, wife entered Central Islip State Hospital for mental illness; recurrent hospitalizations in 1940s and 1950s; painted his first abstract work. 1947, continued abstraction with "white paintings." During mid-forties, in contact with Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock. 1950, first one-man exhibition at Egan Gallery, New York; also represented in Young Painters in U.S. and France at Sidney Janis Gallery, New York. 1951, co-organizer of Ninth Street Show, New York.

Summer 1952, taught at Black Mountain College; 1953–54, at Pratt Institute night school. 1954, one-man show of large paintings, Institute of Design, Chicago; nine paintings included in Twelve Americans, Museum of Modern Art. Work shown at Venice Biennale. 1957, in Eight Americans, Sidney Janis Gallery. Five pictures in The New American Painting, circulated in Europe by Museum of Modern Art. 1960, ten works in Venice Biennale; awarded Italian Ministry of Public Instruction Prize; June–July, traveled in Italy, then returned to U.S.

Honorable mention, Guggenheim International Award Exhibition. 1961, awarded Flora Mayer Witknowsky Prize at the 64th American Exhibition, Art Institute of Chicago. Rheumatic heart condition discovered. 1962, suffered heart attack in February; unable to paint. Died 13 May 1962, New York.

From 1935 to 1938, at a time when many American painters were employed by the Works Progress Administration, Kline was studying in London. Nevertheless, the Depression-era themes of city and labor that were important to many WPA artists were adopted by Kline as well when he returned to America and settled in New York City. In Palmerton, Pa. (1941), the artist depicted a rural equivalent of urban bleakness. Palmerton, near Kline's home town of Wilkes-Barre, is portrayed as a dingy, unprosperous hill town. The palette seems tinged with soot, buildings cluster insubstantially against the hillside, and even the train is deprived of a sense of power or speed. Although it is stretching it to claim to perceive the roots of his mature Abstract Expressionist work in this small painting, Kline does fill the canvas from bottom to top with hills, and spatial recession is sacrificed to an overall surface of broadly painted forms. The painting was exhibited in 1943 at the annual exhibition of the National Academy of Design and won the $300 S.J. Wallace Truman Prize.

Kline's large, gestural, black-and-white canvases established his reputation in 1951 and became synonymous with his name in the public mind. In addition to Merce C, the [Smithsonian American Art] museum owns another major black-and-white Kline of 1961, an untitled work. Using acrylic paints, he produced a complex surface in which white is admixed with gray tones. As always, Kline painted the white as much as the black; it is not black on white but a dynamic dialogue between the two. The racing horizontals across the bottom supply a sure sense of gravity, but also refuse to respect the lateral boundaries of the canvas. Their great trajectory pushes the edge outward, and the slightly tilted verticals, like the stack of an ocean liner, add to the sense of speed.

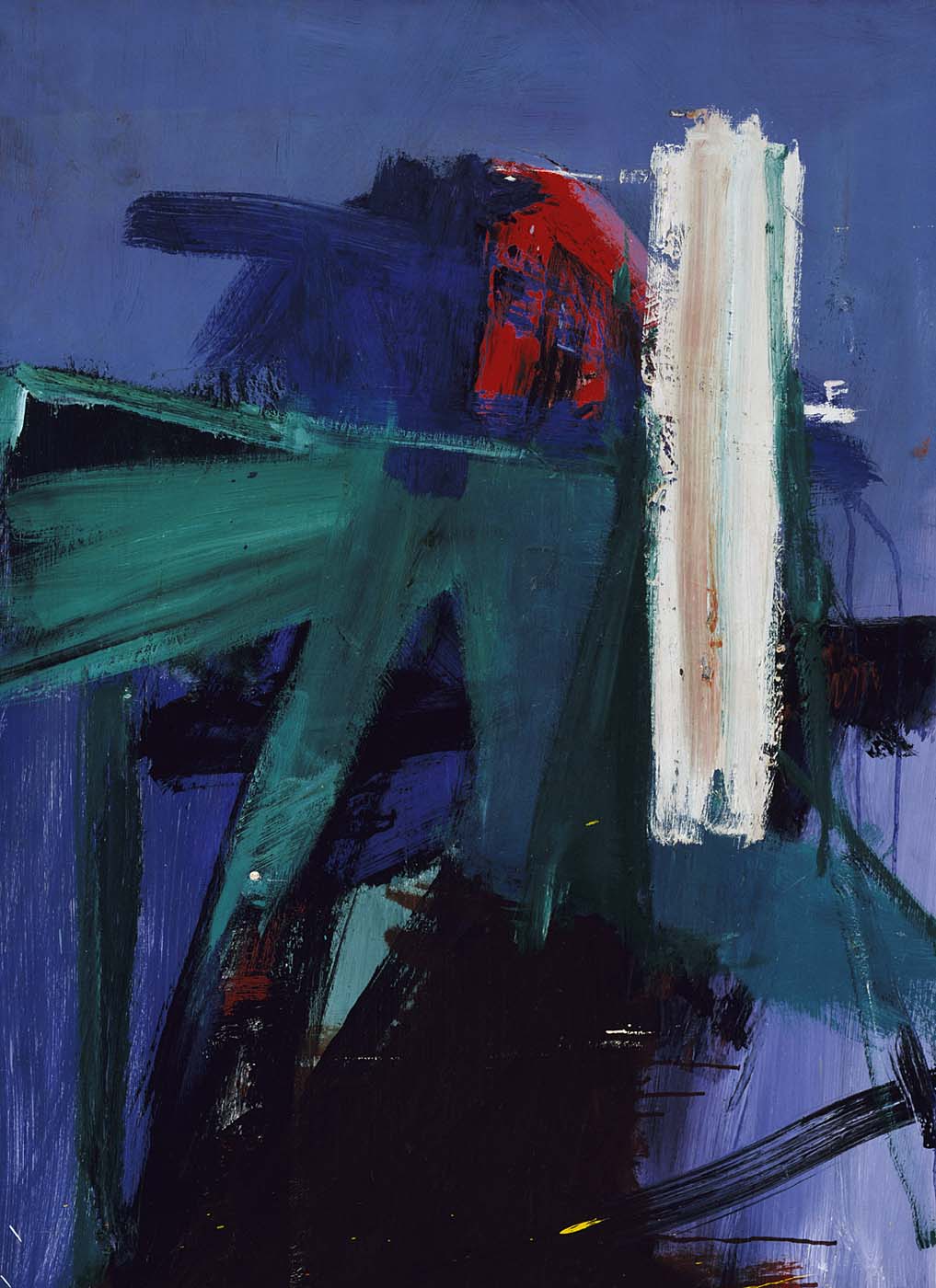

Although he is often thought of as only working in black and white, in fact Kline used color throughout his career. While black-and-white paintings dominated the early fifties, about 1956 color began to reassert itself in his work. Two paintings of modest size in the [Smithsonian American Art] museum, both from the end of the decade, represent this development. Blueberry Eyes (1959–60) reverberates with the deep, saturated blue of the fruit. Simultaneously dynamic and structural like the black-and-white paintings, it differs from them in that the warm color suggests spatial or atmospheric depth. An untitled oil-on-paper painting (ca. 1959), despite its small size (24 X 18 1/4 in.), is more complex and agitated in drawing and structure, and more varied and intense in color. Black is used as well for the skeletal shape brushed brashly over the red, green, and yellow field. Both of these late color paintings embody a vein of emotionalism that Kline mined toward the end of his life. Cut short by his death at fifty-one, Kline's developing art is full of confidence, as evidenced by this imposing late work. Like the large, late black-and-whites in the NMAA, Kline's color works suggest enormous potential that was destined to remain unrealized.

William Kloss Treasures from the National Museum of American Art (Washington, D.C. and London: National Museum of American Art with the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985