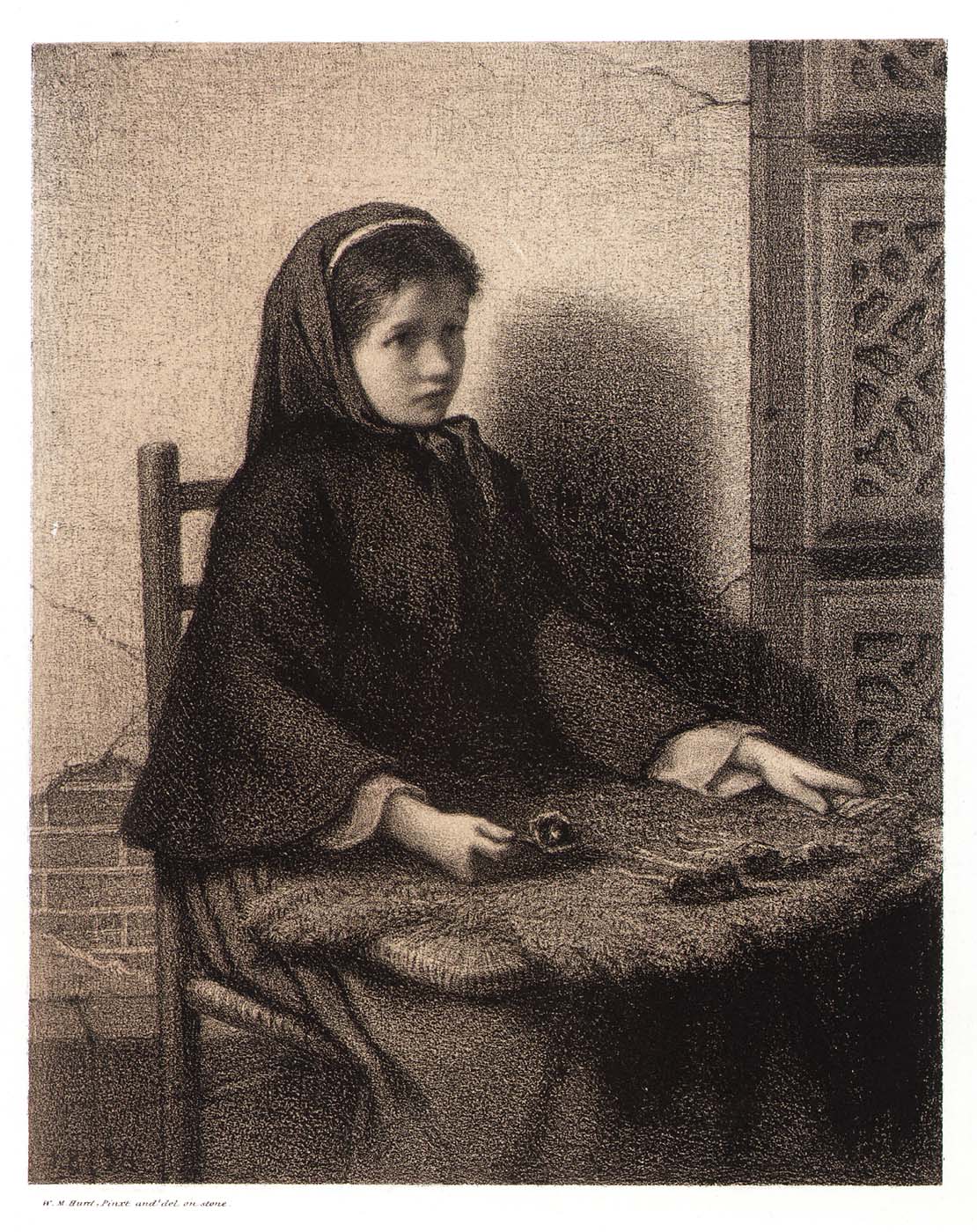

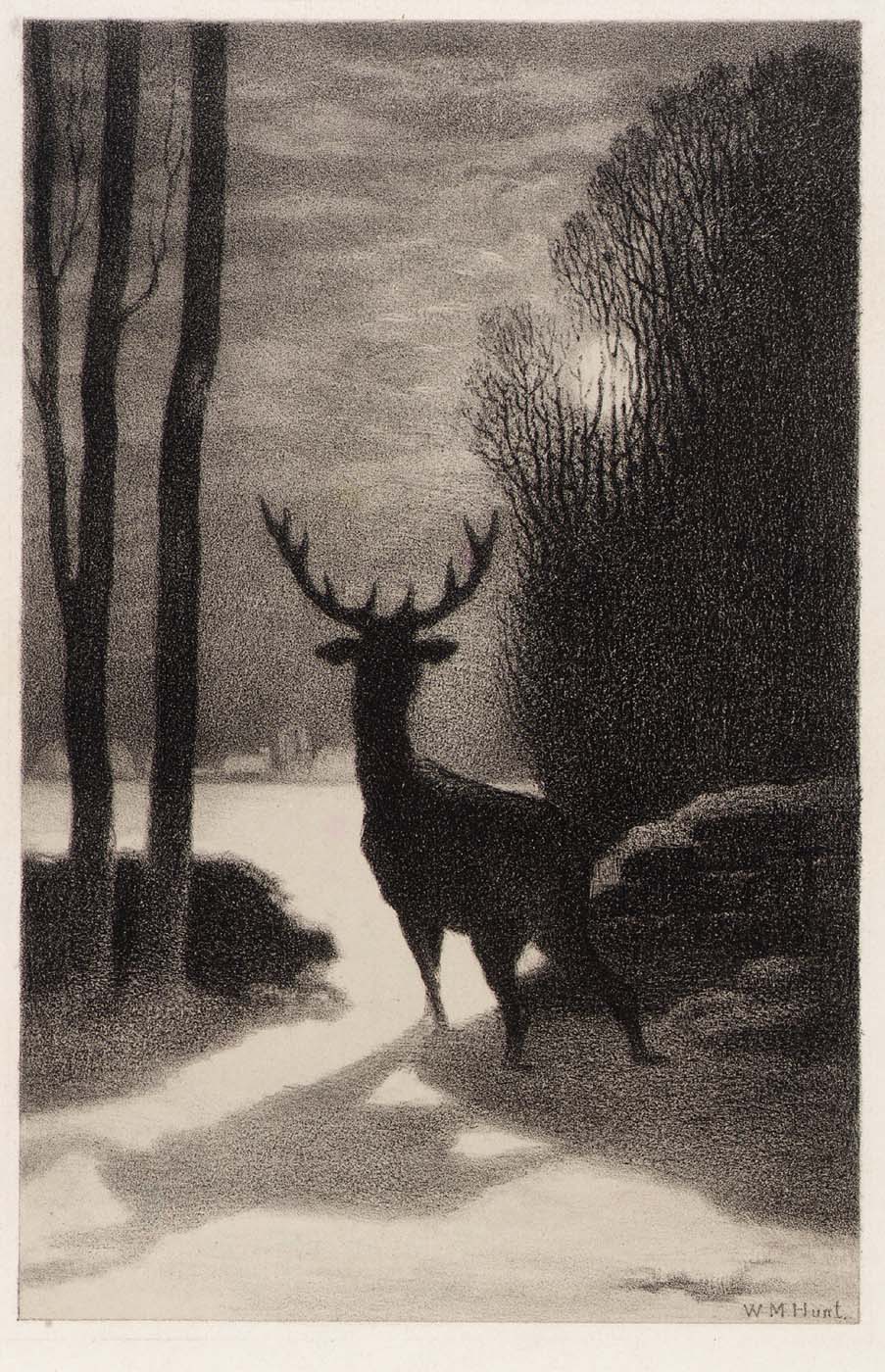

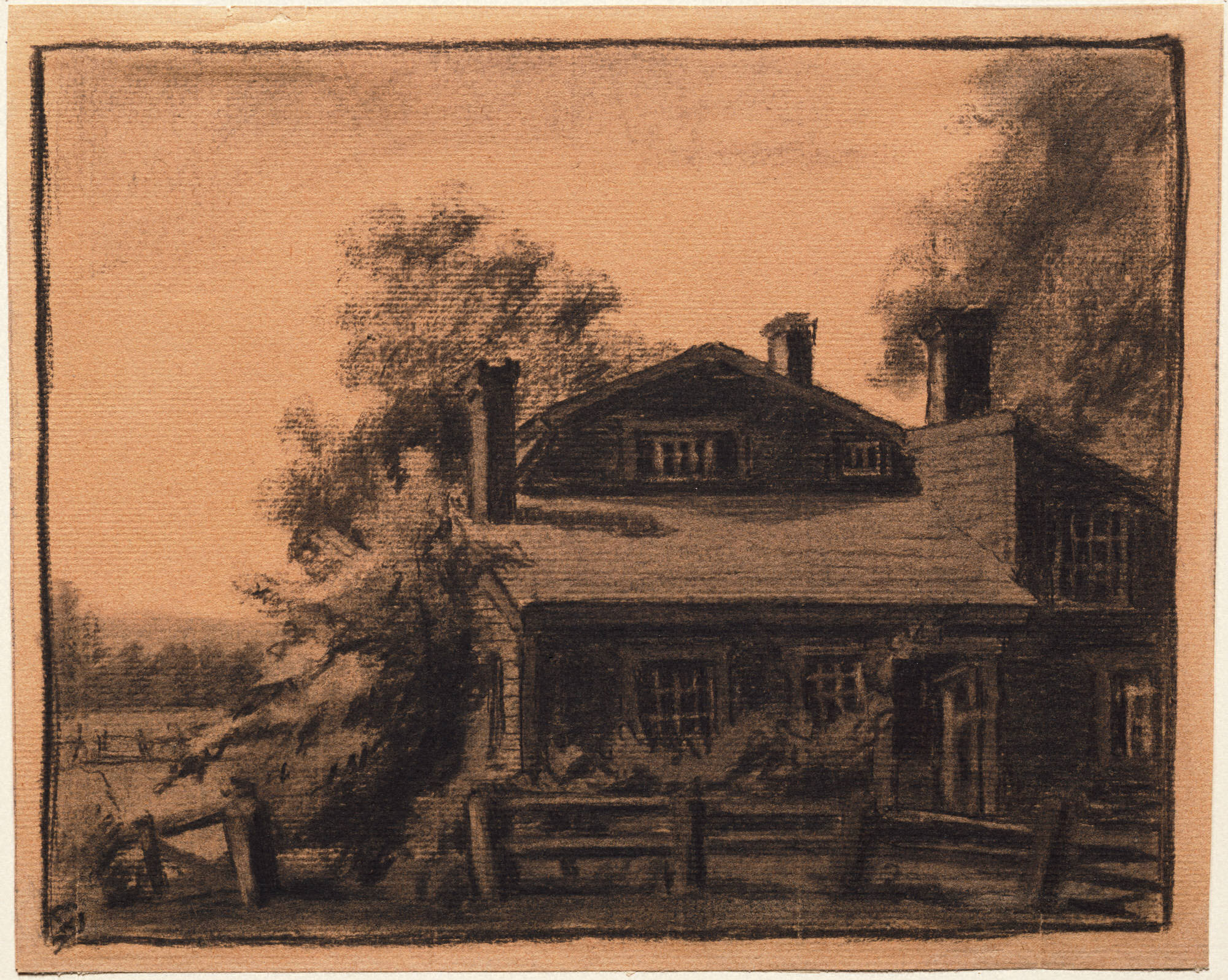

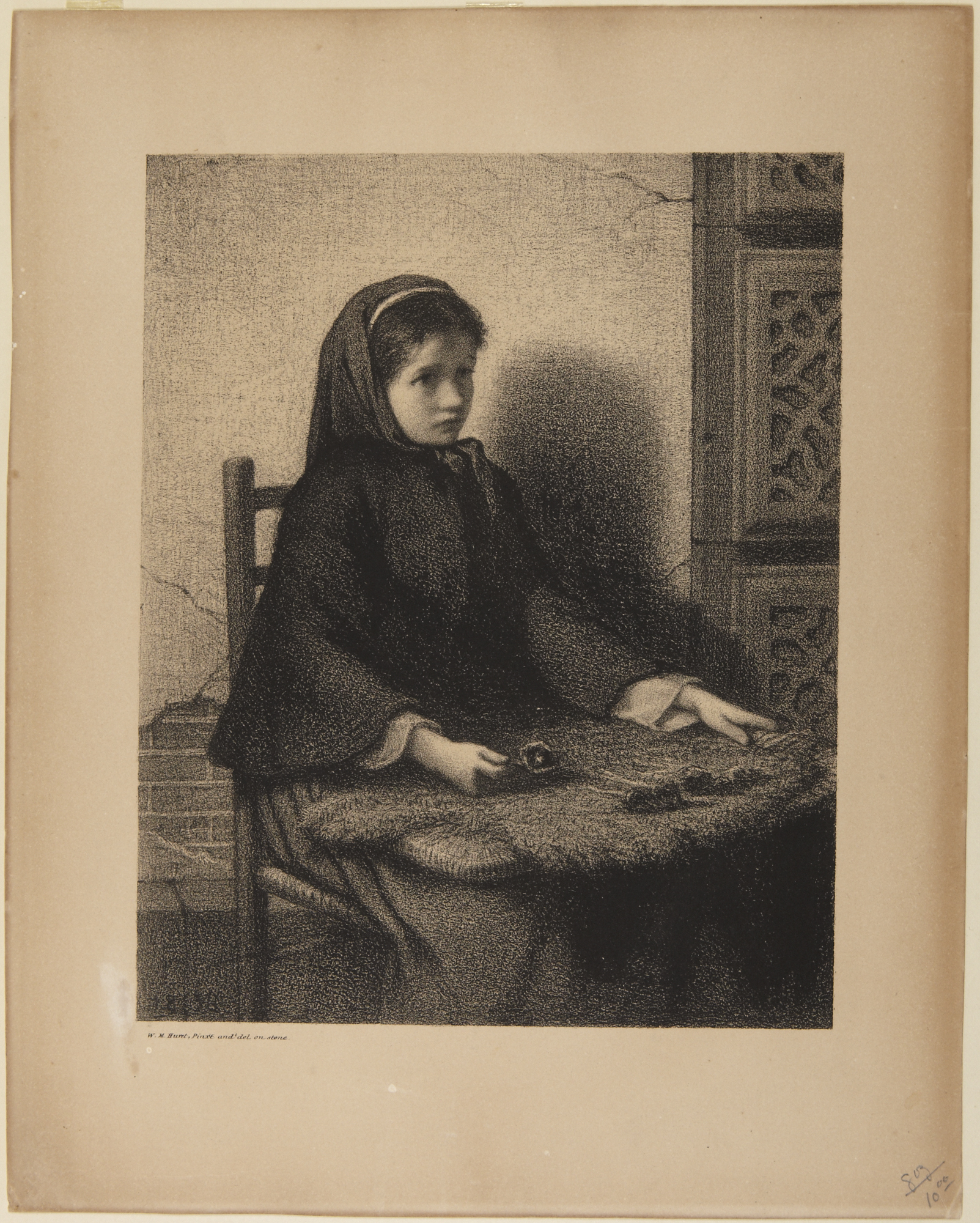

William Morris Hunt

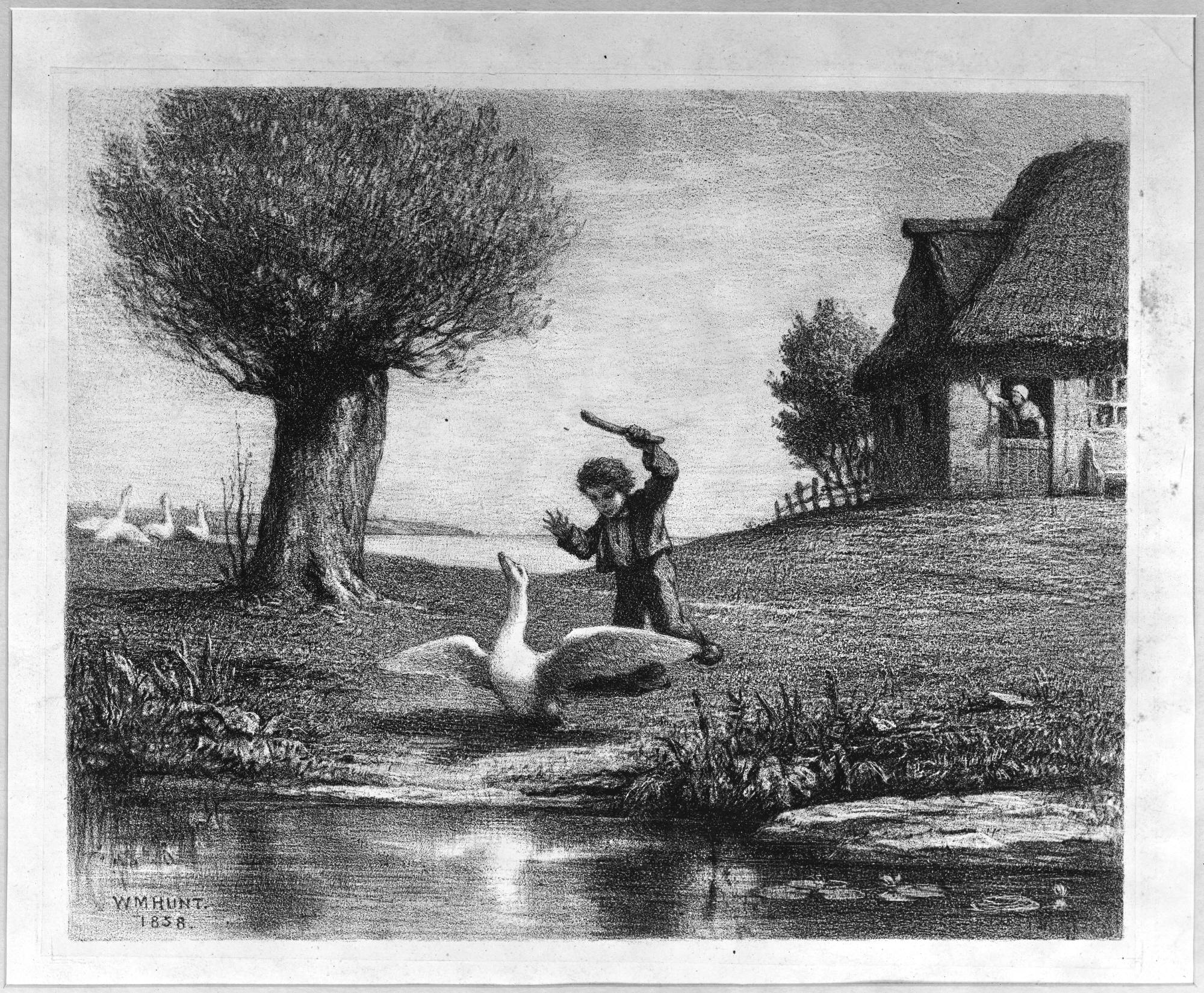

Hunt was the son of a Vermont congressman. He learned to draw at an early age, his first teacher being an Italian artist named Gambadella. After leaving Harvard College in his third year, Hunt was taken in 1844 by his widowed mother and her other four children to the south of France. After travel in the Middle East, they stopped in Rome where William did some drawing in the studio of American sculptor, Henry Kirke Brown. In 1845, he entered the Düsseldorf Academy, but left the next year for Paris where he became a pupil of Thomas Couture from 1846 to 1852. The sight of Millet's The Sower at the Salon of 1851 in Paris inspired Hunt to spend most of the next two years with Millet at Barbizon. Hunt returned to the United States in 1854 and two years later moved to Newport, Rhode Island, where he painted and took a few pupils. In 1862, he settled permanently in Boston where the demand for his portraits grew as did the size and popularity of his classes. His last trip to Europe was made in 1867. The great Boston fire of 1872 destroyed Hunt's Summer Street studio and with it his collection of French paintings. He traveled to Mexico in 1875 and in the same year was commissioned to paint two murals for the new State Capital at Albany, New York. Shortly after their completion (and rapid demise due to faulty installation), Hunt drowned off the coast of New Hampshire.

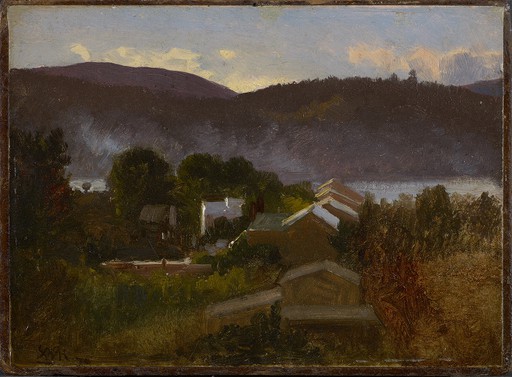

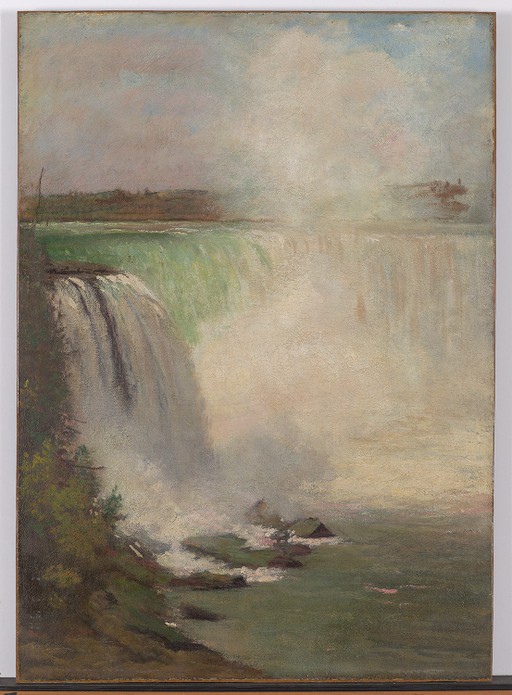

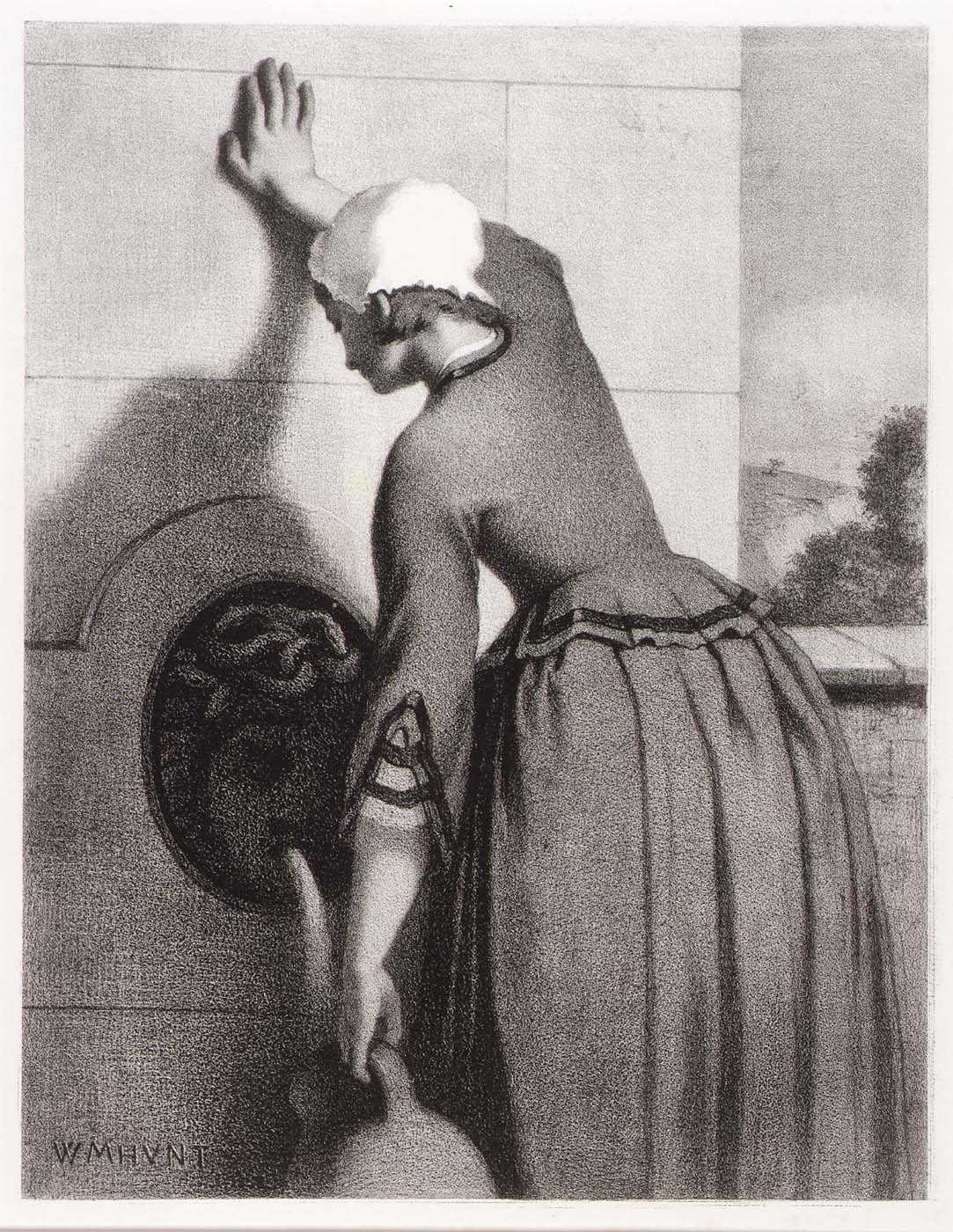

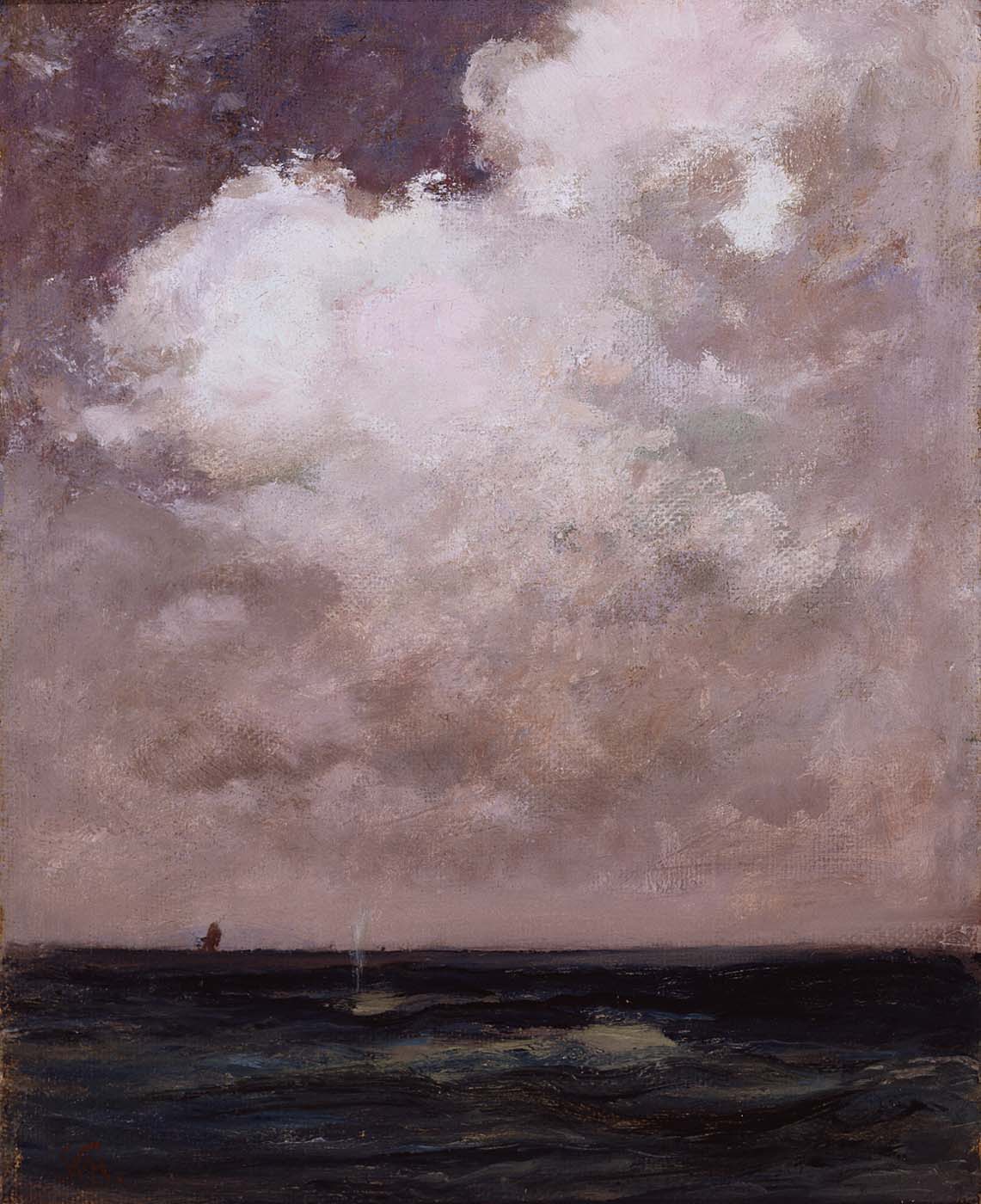

The aversion of many Easterners to French art was regarded by Hunt to be an "unpardonable conceit" and to balance the record, he encouraged and supported a bevy of younger American artists as well as numerous patrons and collectors in the Boston area. The lessons wrought from his training with Couture and Millet added to his ready wit and compelling presence gave Hunt more than enough equipment to articulate the aesthetic concerns of these men as well as those of several other French artists, especially from among the Barbizon group. Hunt preached a gospel of directness, simplicity, harmony of effect, and a willingness to accept the relative beauty of even the most common subjects. Although one of New England's finest portraitists for over twenty years, Hunt made no secret of his difficulties in painting convincing landscapes, finding natural light and the constant changes it effects a particularly vexing problem. As a result, even his most charming landscapes (which are usually more indebeted to Corot or Daubigny than to Millet) give the appearance of a shorthand method grafted on to a studio design—usually one derived from from the many charcoal sketches, which Hunt was especially fond of executing.

Peter Bermingham American Art in the Barbizon Mood (Washington, D.C.: National Collection of Fine Arts and Smithsonian Institution Press, 1975