Edward Mitchell Bannister

"All that I would do I cannot—that is, all I could say in art —simply from lack of training, but with God's help I hope to deliver the message he entrusted to me." George W. Whitaker, "Reminiscences of Providence Artists," Providence Magazine, The Board of Trade Journal (Feb. 1914): 139.

Edward Mitchell Bannister's determination to become a successful artist was largely fueled by an inflammatory article he read in the New York Herald in 1867, that stated "the Negro seems to have an appreciation for art while being manifestly unable to produce it." Ironically, less than a decade later, in 1876, Bannister was the first African-American artist to receive a national award.

Bannister was born in November 1828 in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, Canada. His father was a native of Barbados, West Indies. The racial identity of Bannister's mother, Hannah Alexander Bannister, who lived in New Brunswick and whom Bannister credited with fostering his earliest artistic interests, is not known. Bannister's father apparently died early, and after the death of his mother in 1844 he lived with a white family in New Brunswick. Bannister left his foster home after several years and took a job at sea, as was customary for many young men from St. Andrews.

In 1848 Bannister moved to Boston where he held a variety of menial jobs before he became a barber and eventually learned to paint. Bannister painted in the Boston Studio Building, and also enrolled inseveral evening classes at Lowell Institute with the noted sculptor-anatomist Dr. William Rimmer. Only a few of Bannister's paintings from the 1850s and 1860s have survived, preventing a stylistic assessment of his early period in Boston. While Bannister lived in Boston he must have seen and been influenced by the Barbizon School-inspired paintings of William Morris Hunt who had studied in Europe and held numerous public exhibitions in Boston during the 1860s. American landscape painters were increasingly aware of the simple rustic motifs and pictorial poetry of French Barbizon paintings by Jean-Baptiste Corot, Jean-François Millet, and Charles-François Daubigny in the midnineteenth century.

On June 10, 1857, Bannister marriedChristiana Cartreaux, a Narragansett Indian who was born in North Kingston, Rhode Island. The couple had no children. Christiana worked as a wigmaker and hairdresser in Boston, and her Rhode Island background might have prompted the Bannisters to move from Boston to Providence, Rhode Island, in 1870.

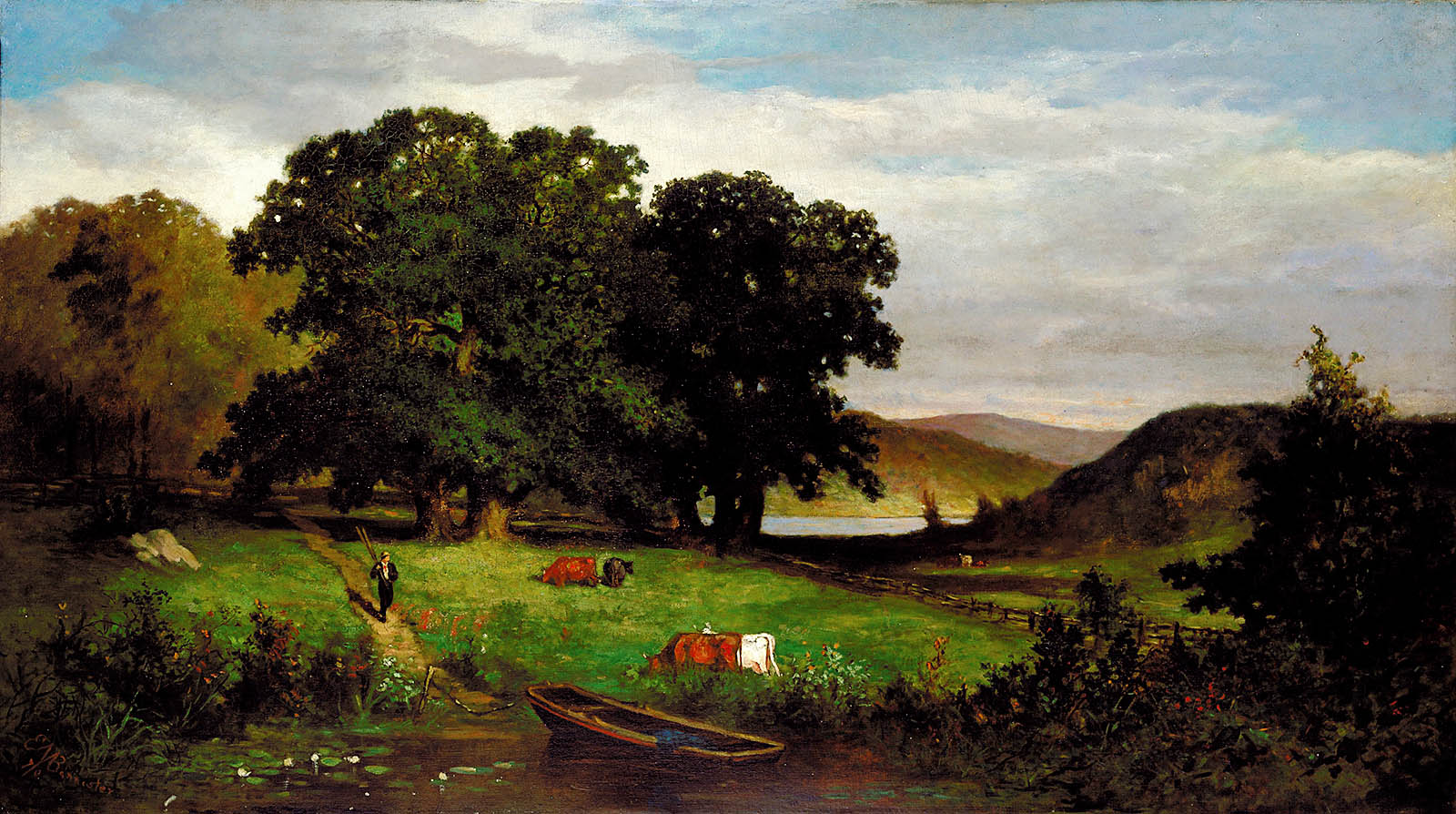

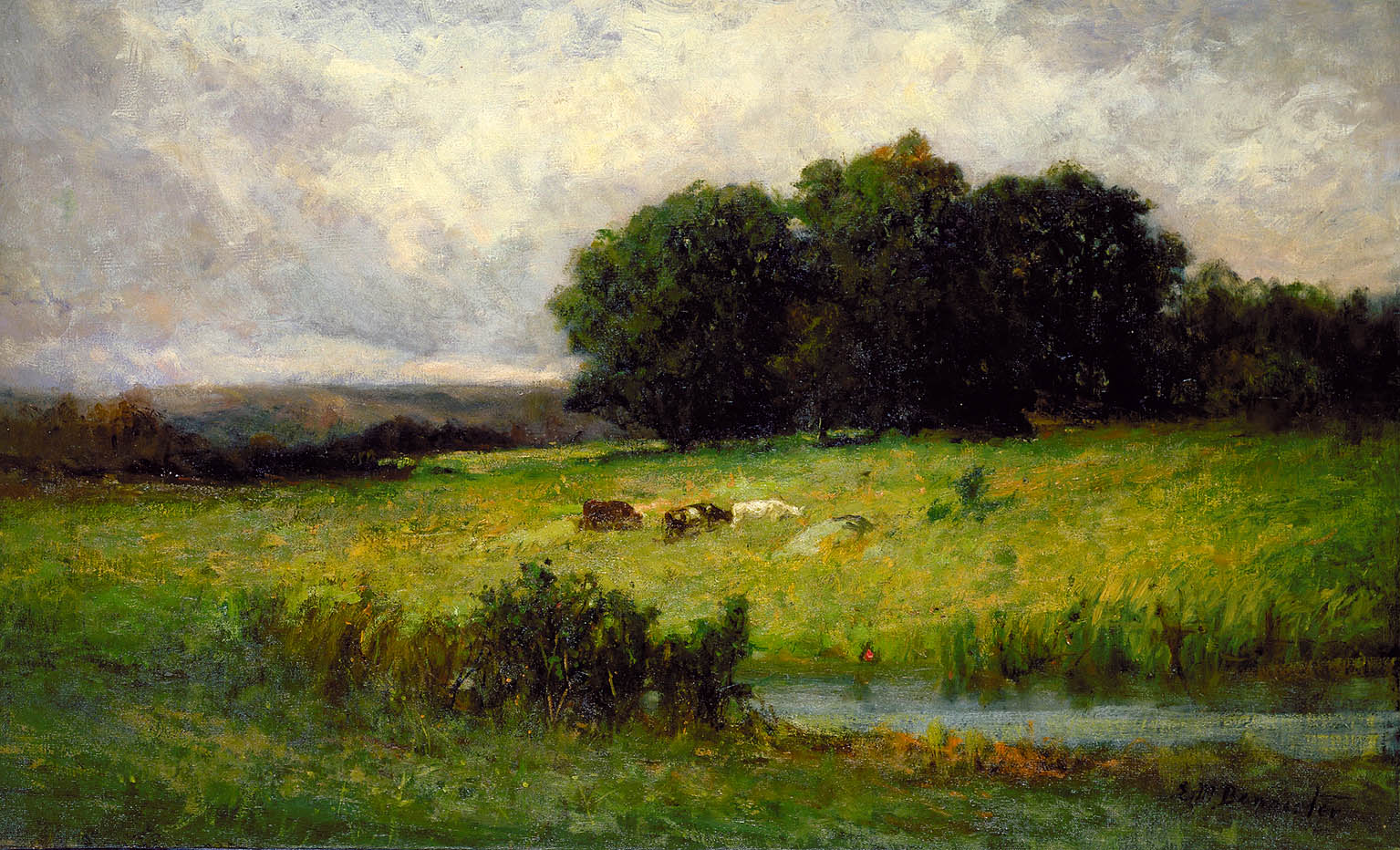

Since Bannister's artistic studies were limited, it is remarkable, indeed, that within five years after his arrival in Providence, one of Bannister's paintings was accepted in thePhiladelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876. The painting, Under the Oaks, was selected for the first-prize bronze medal. Bannister related in considerable detail that the judges became indignant and originally wanted to "reconsider" the award upon discovering that Bannister was African American. The white competitors, however, upheld the decision and Bannister was awarded the bronze medal. The location of the painting has not been known since the turn of the century.

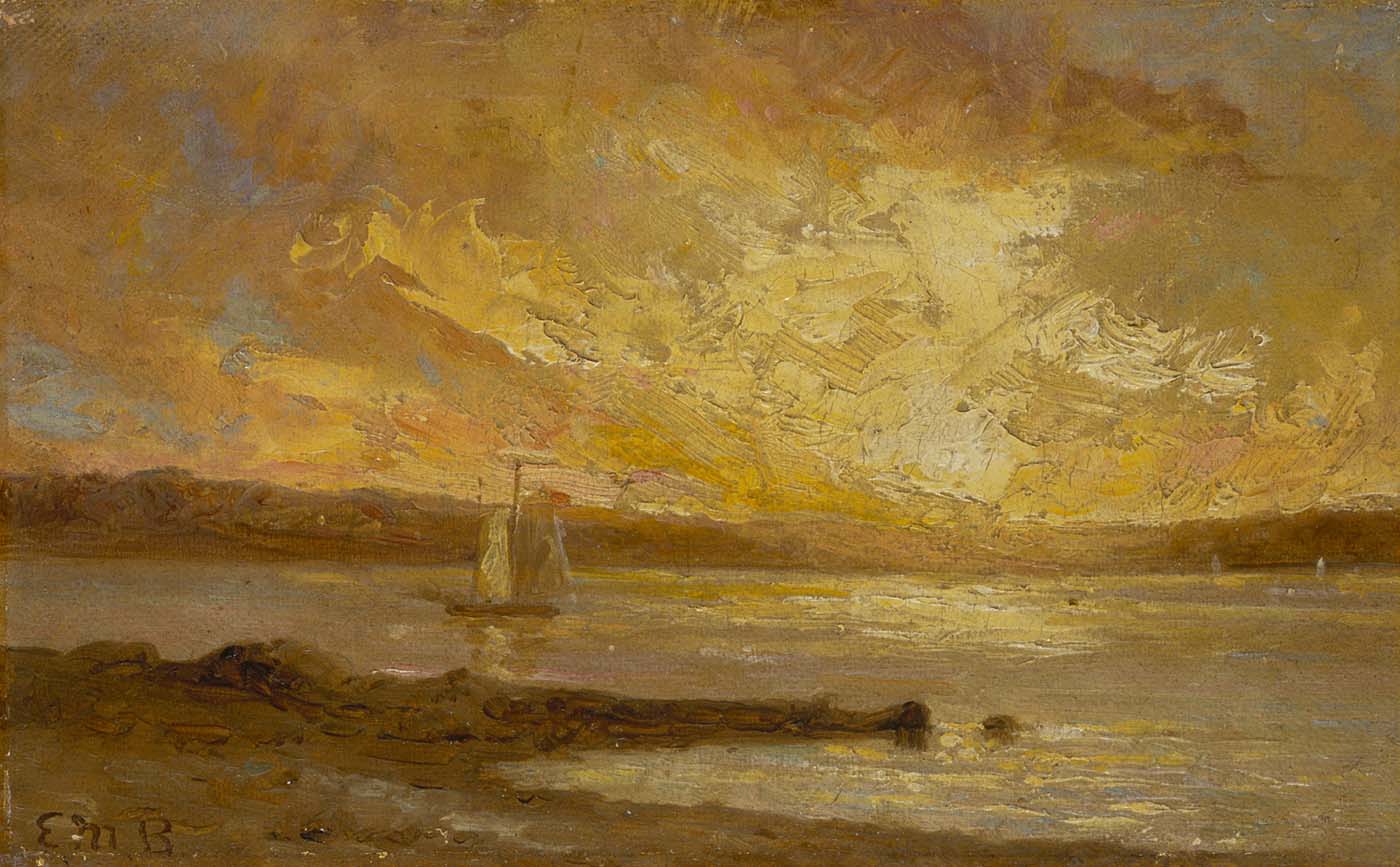

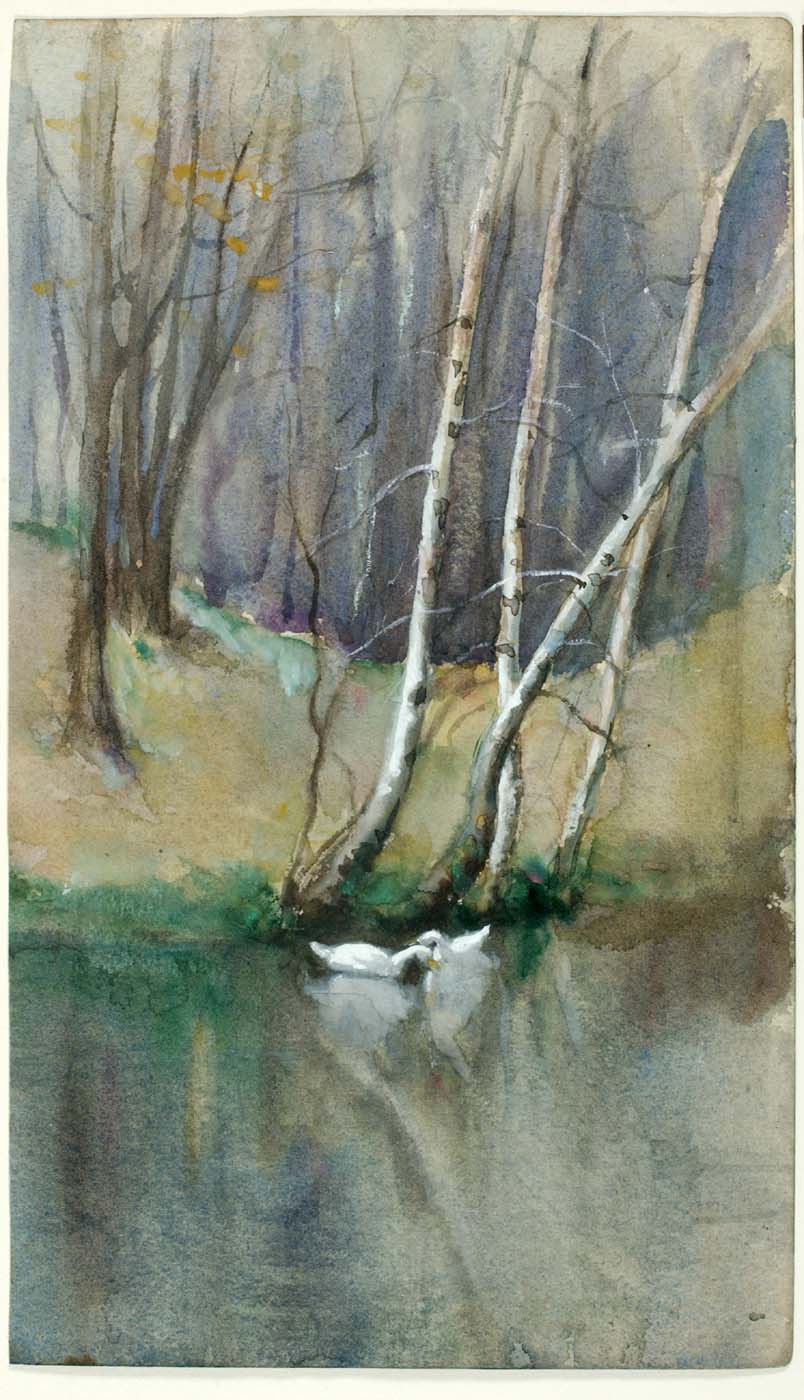

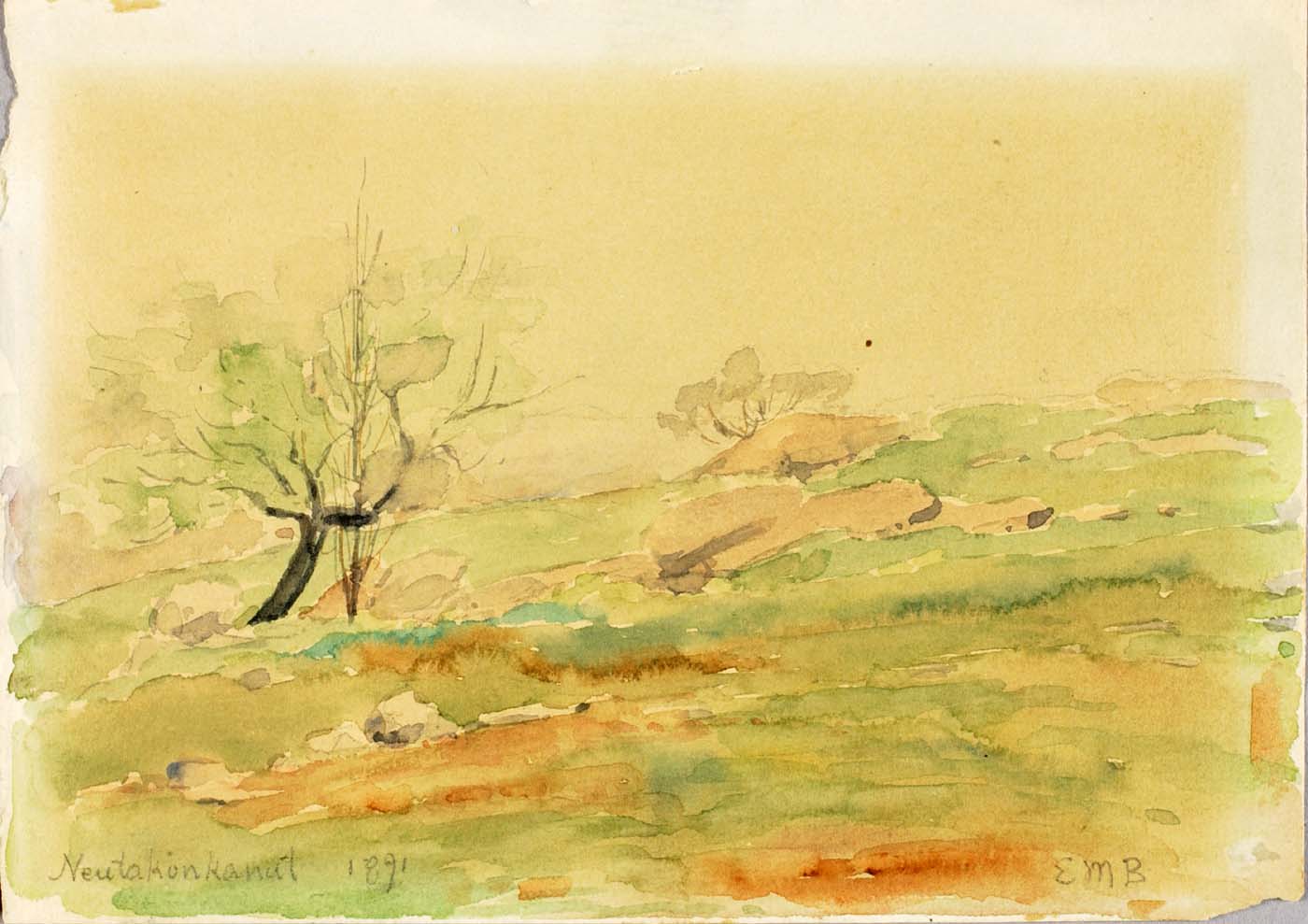

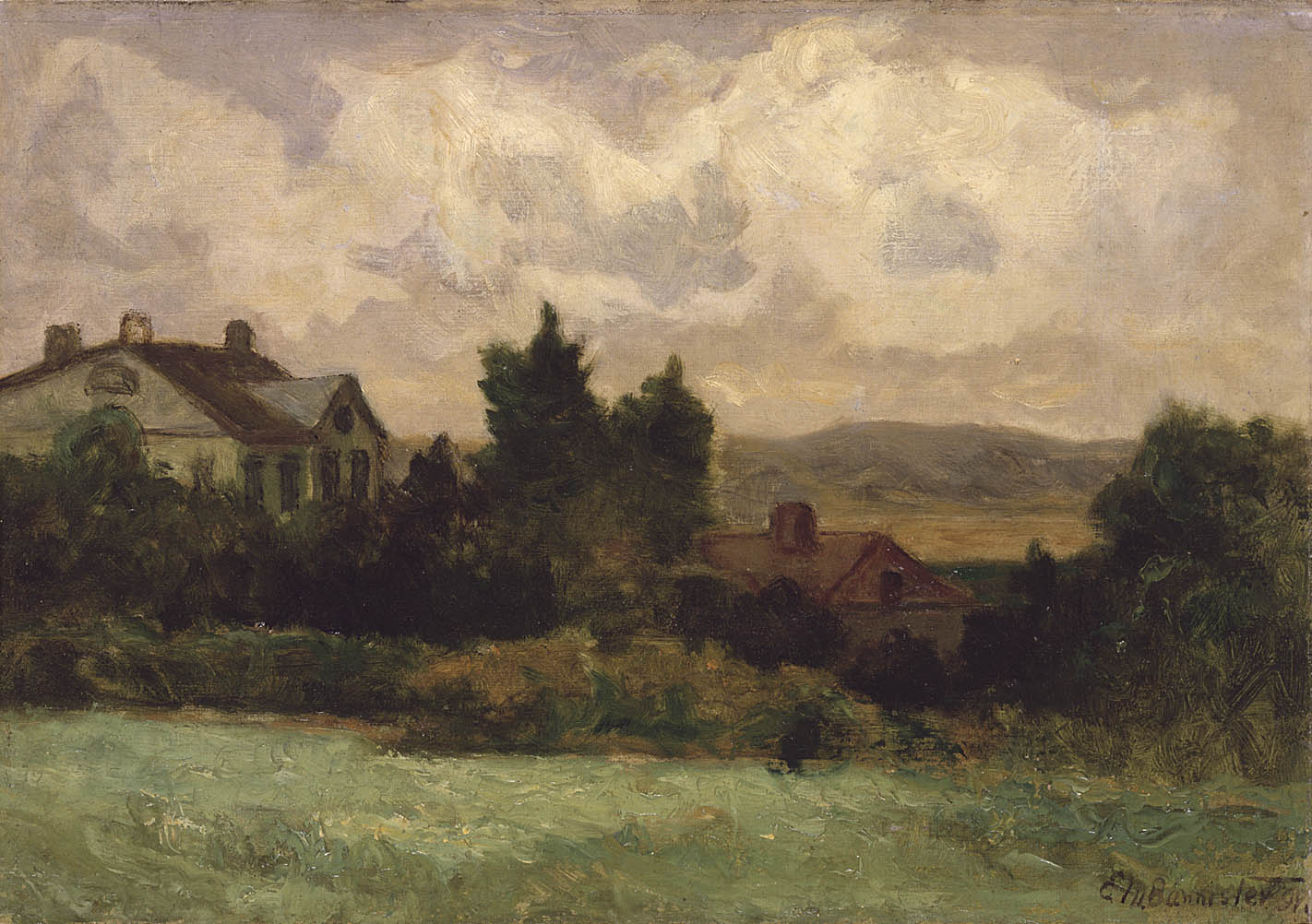

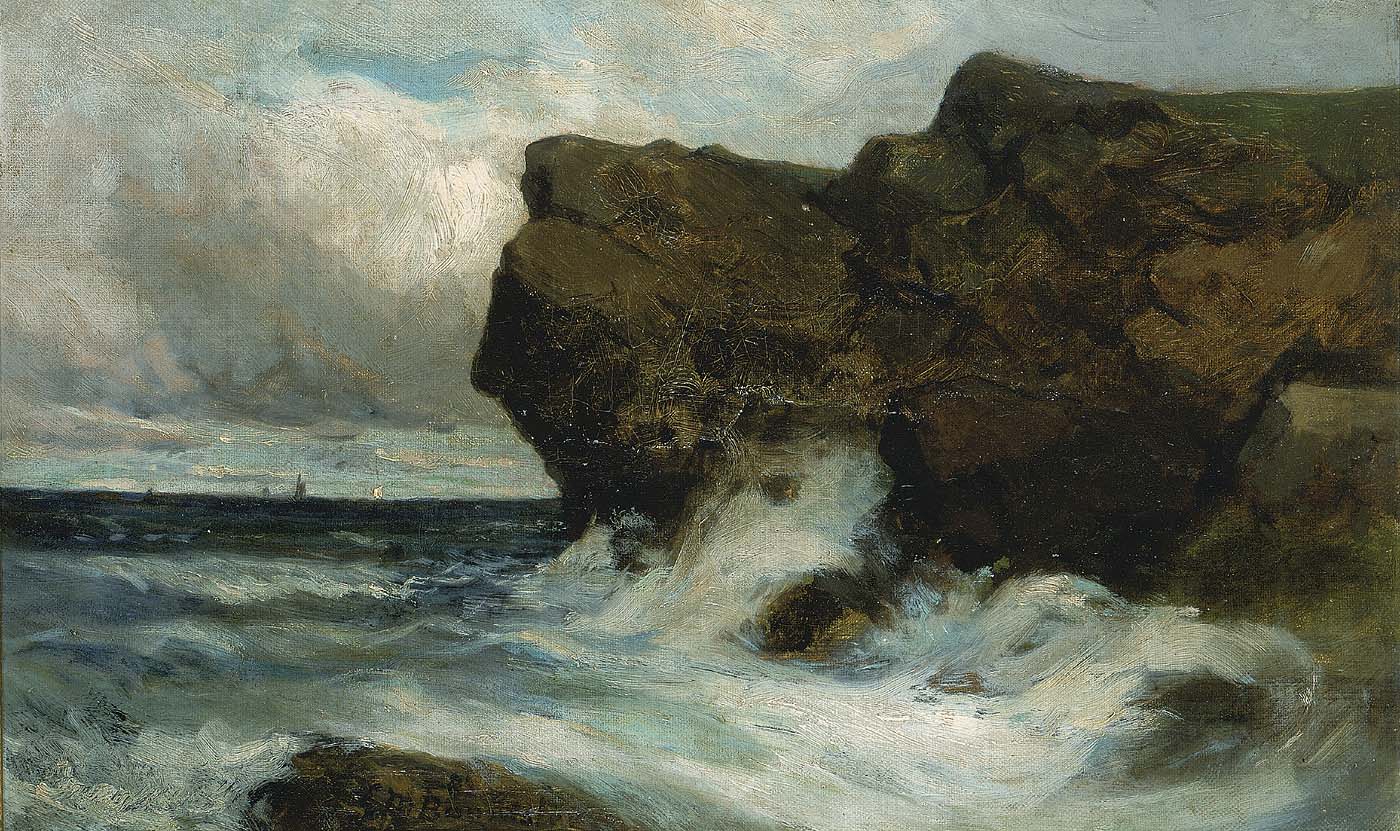

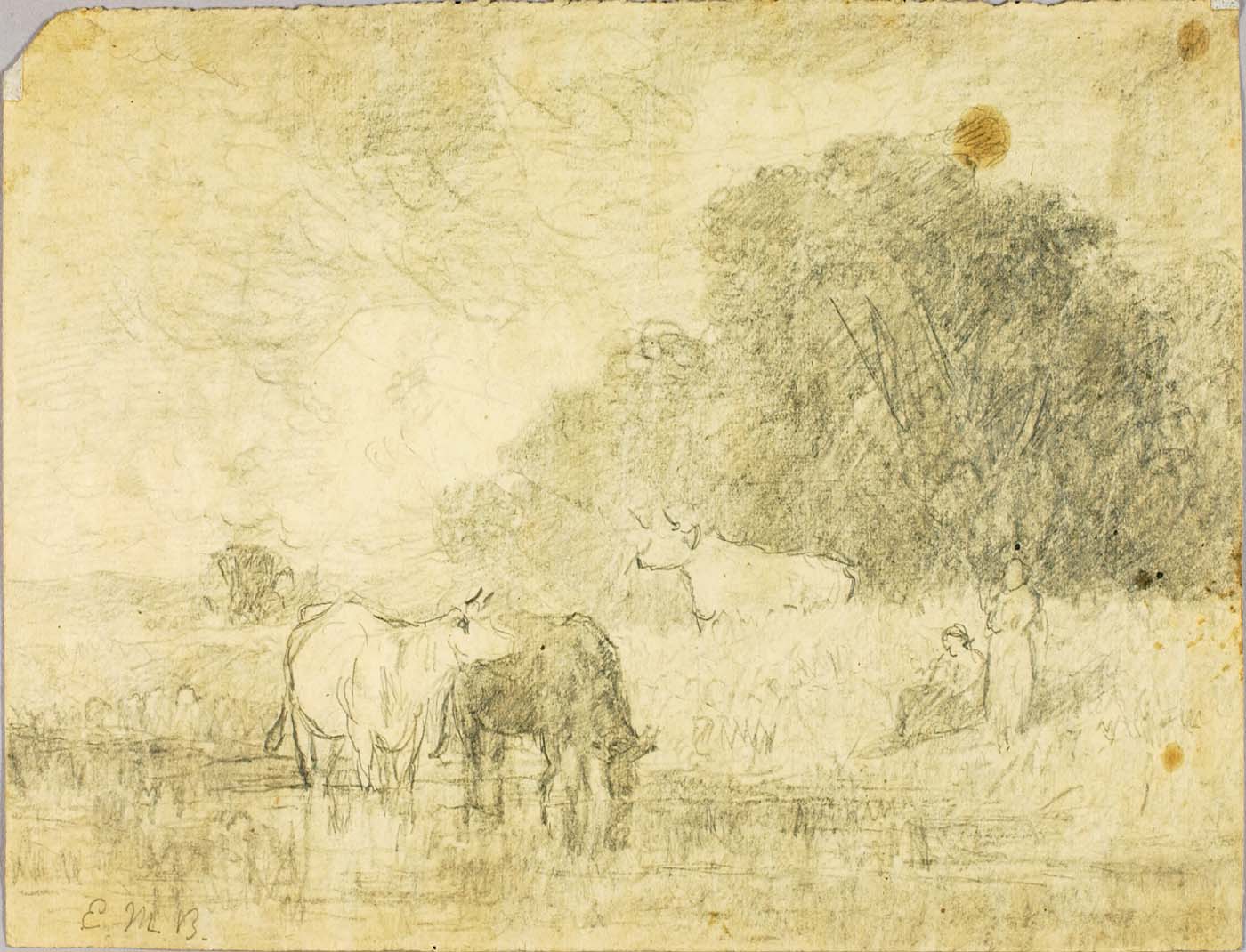

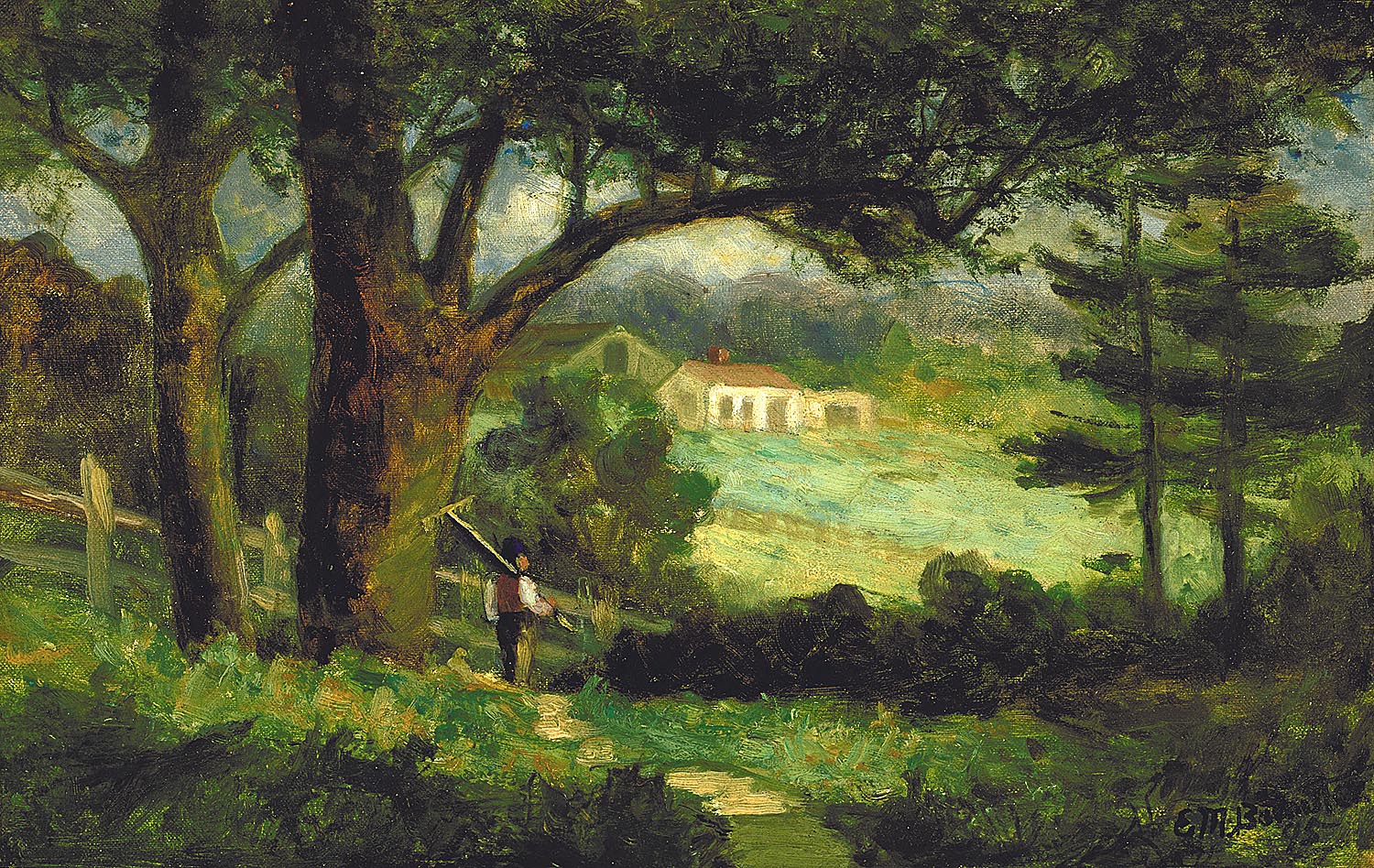

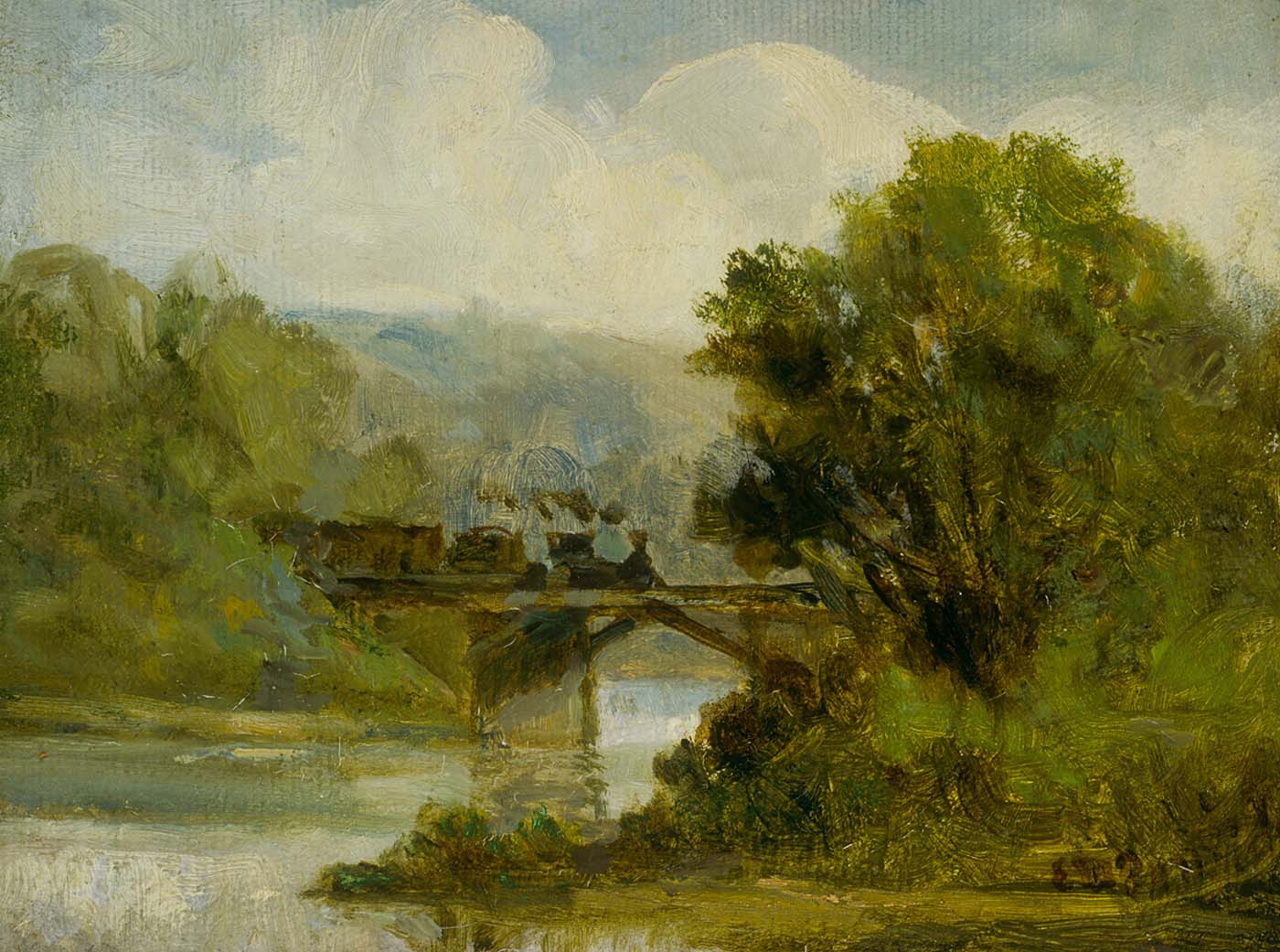

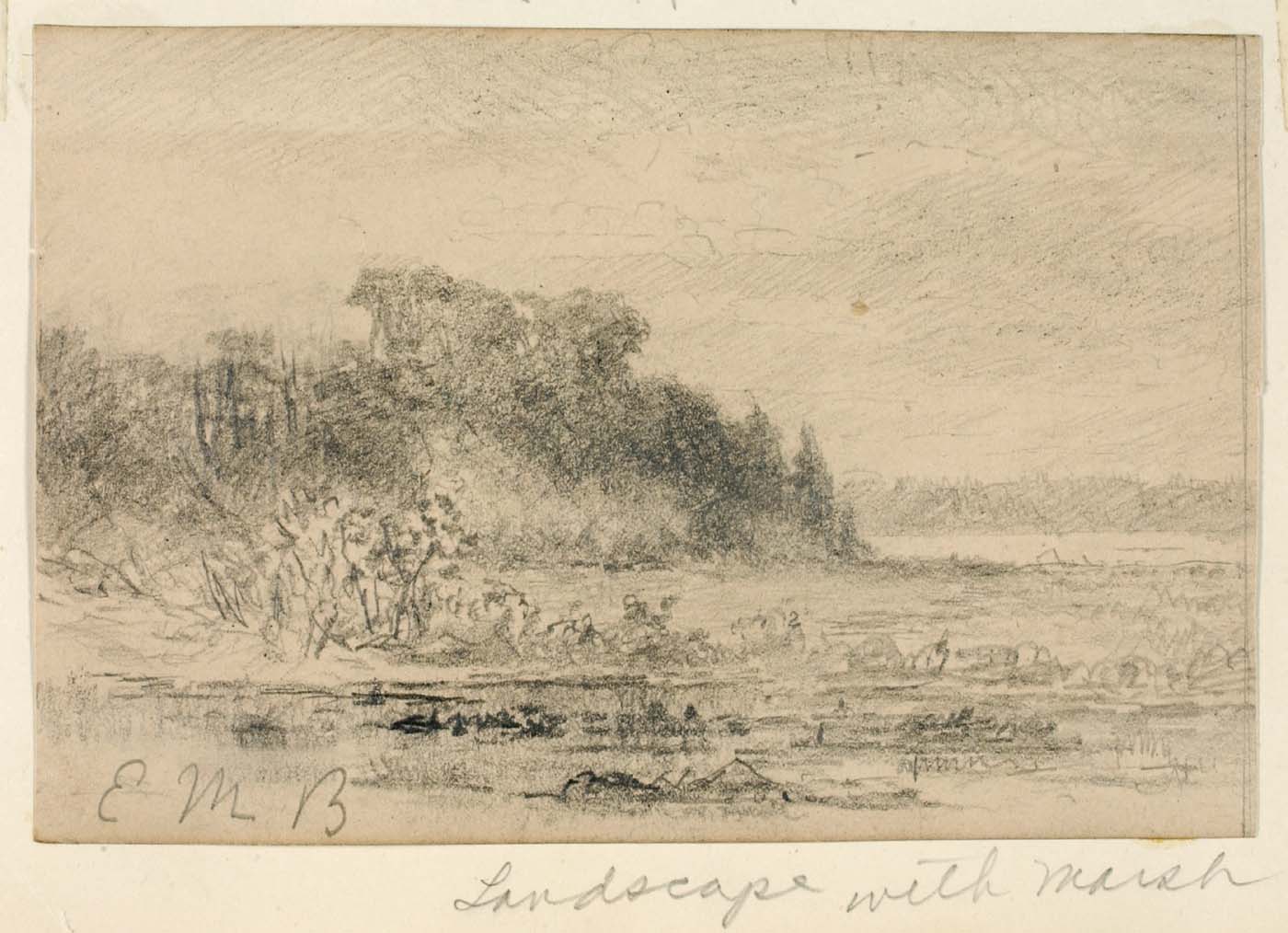

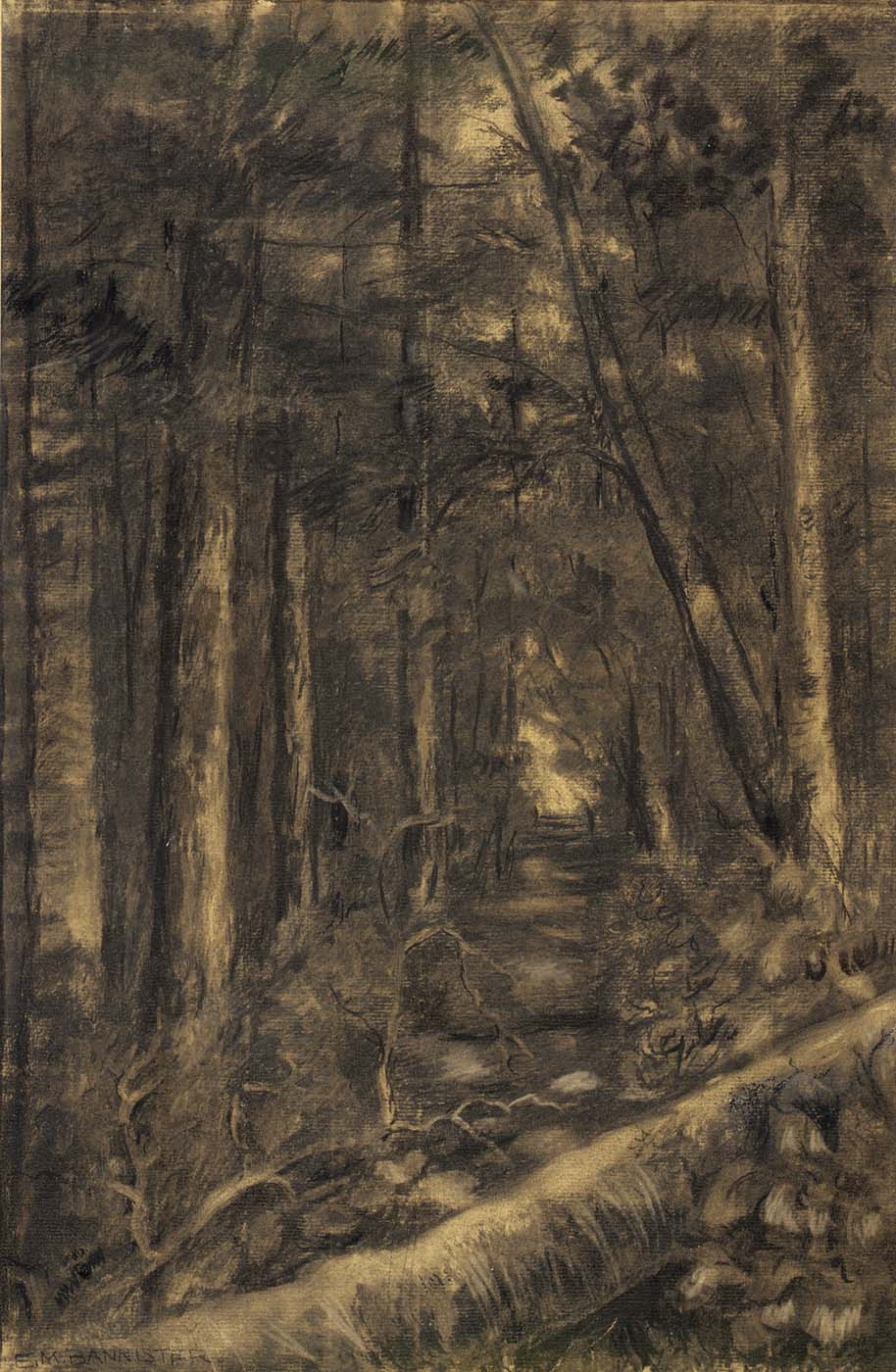

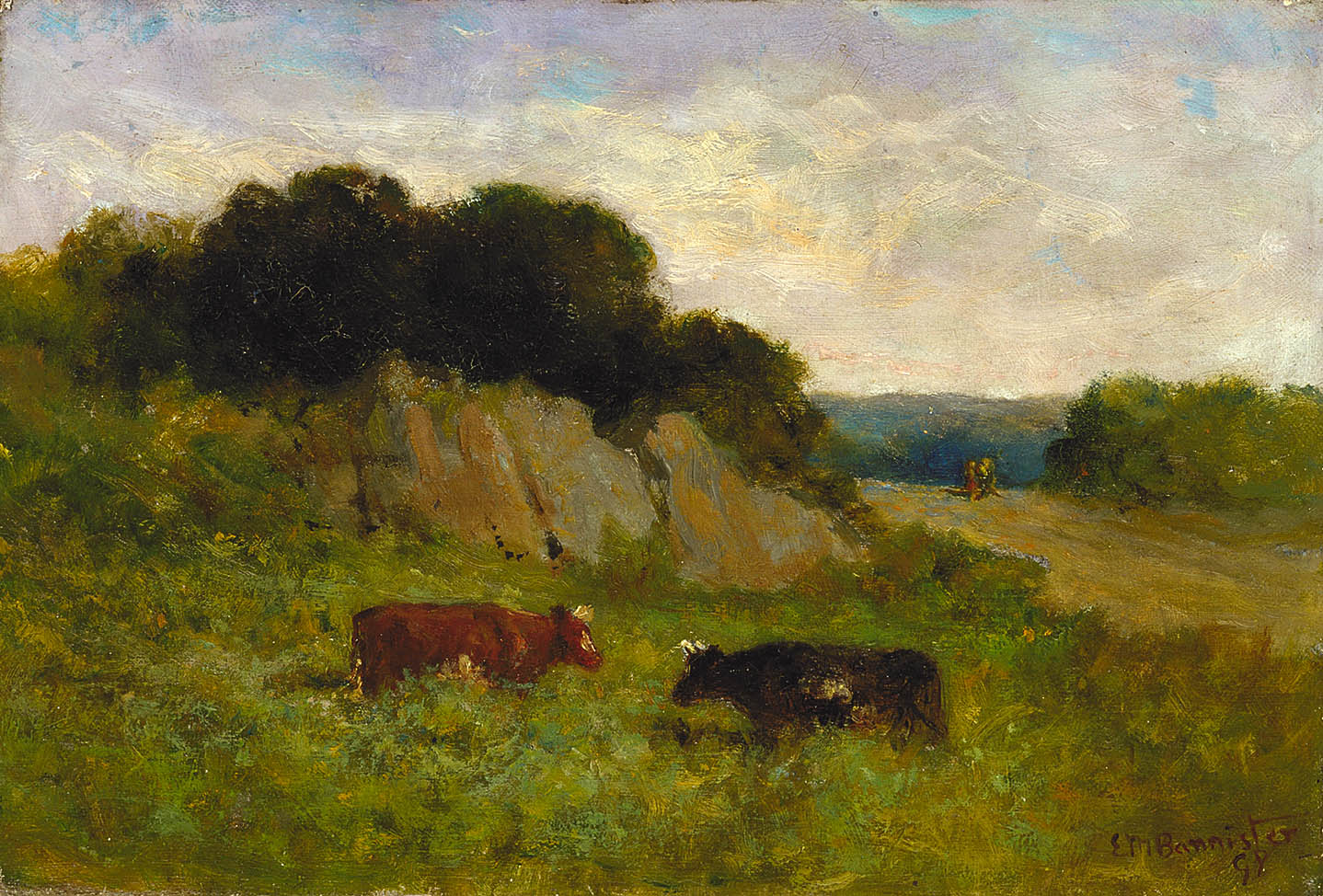

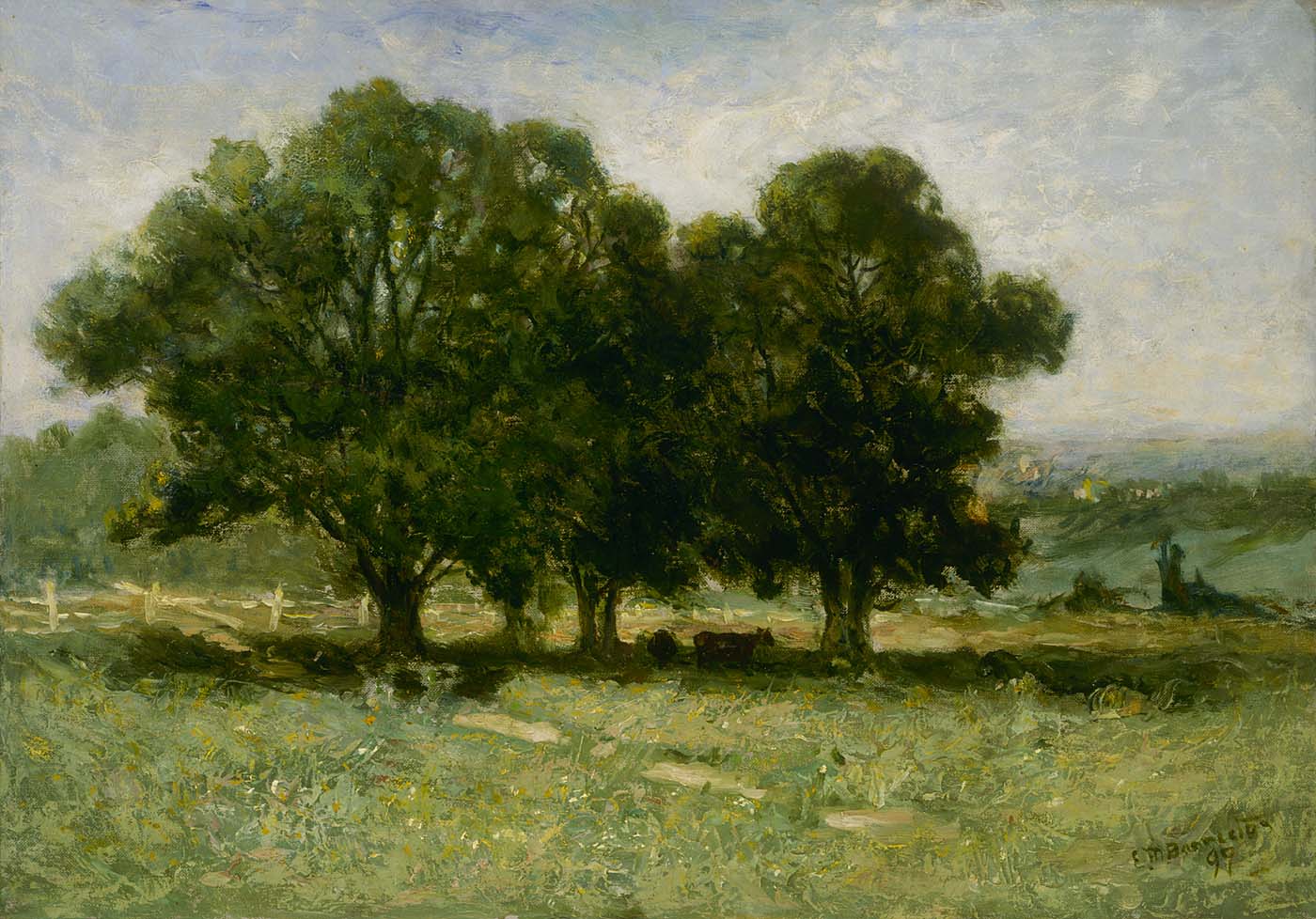

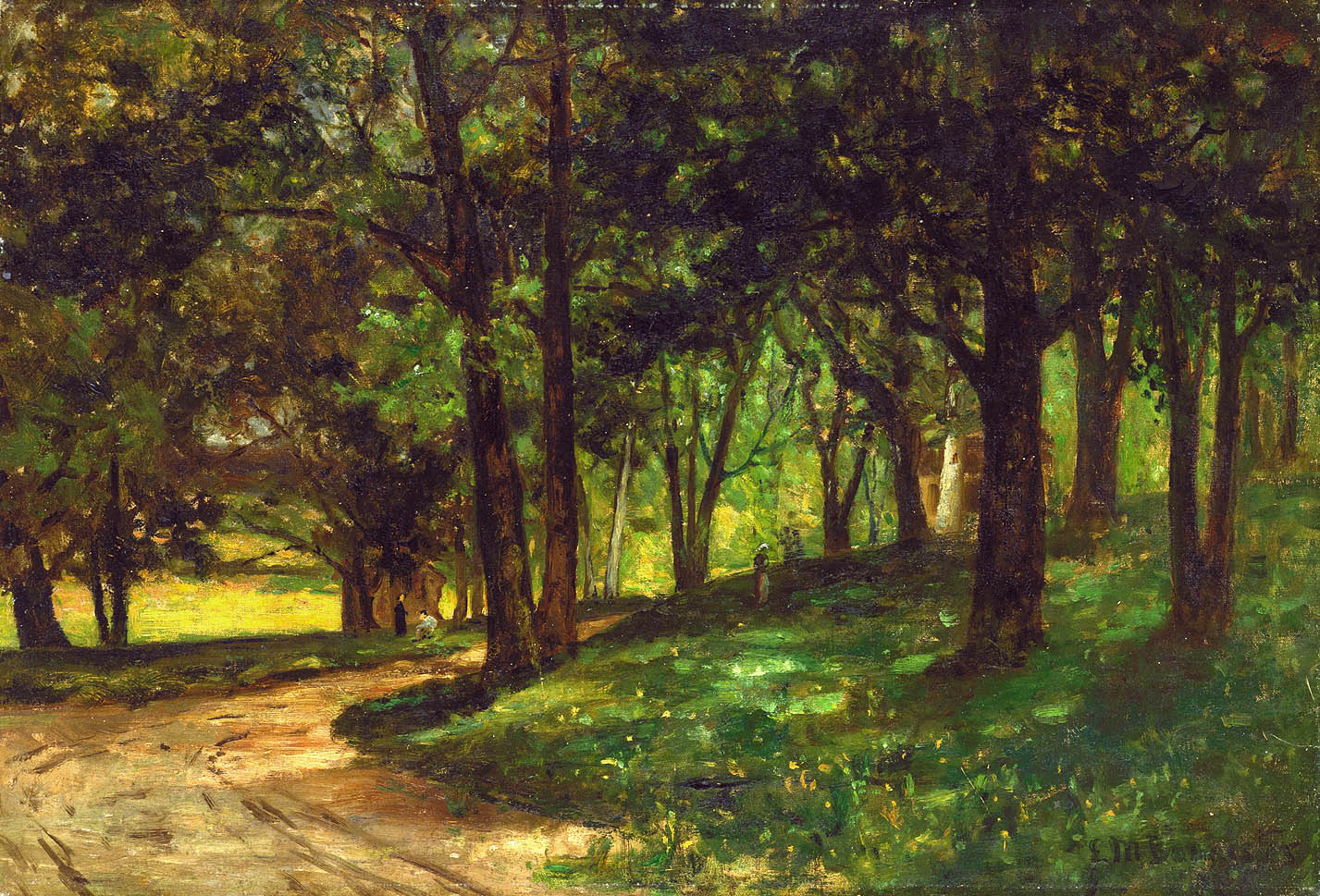

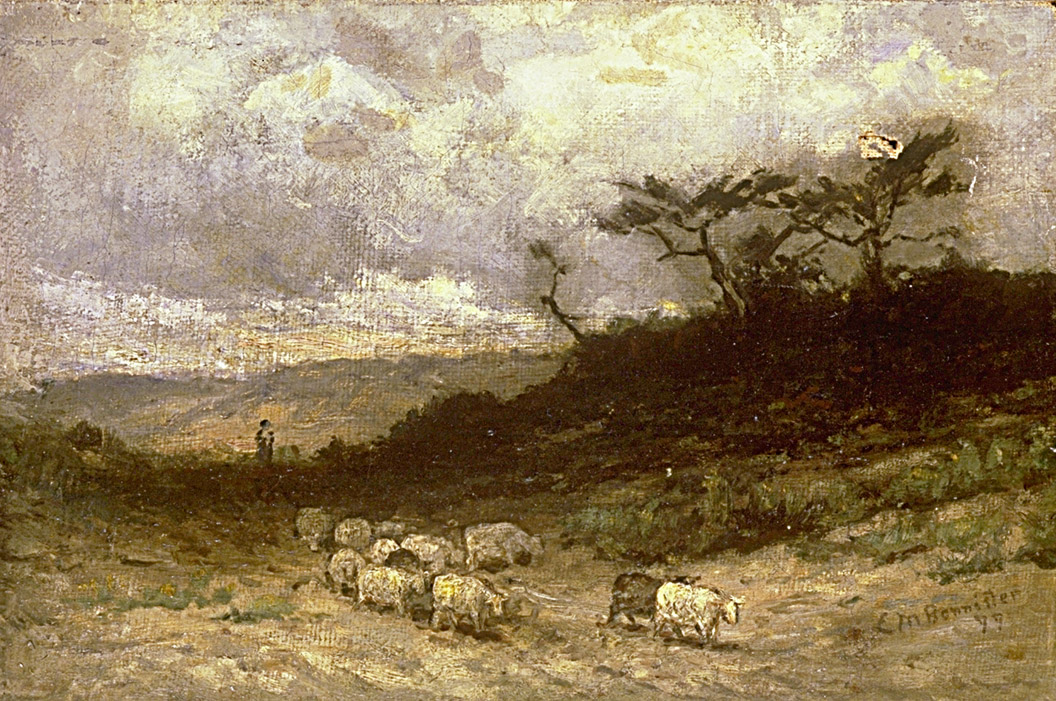

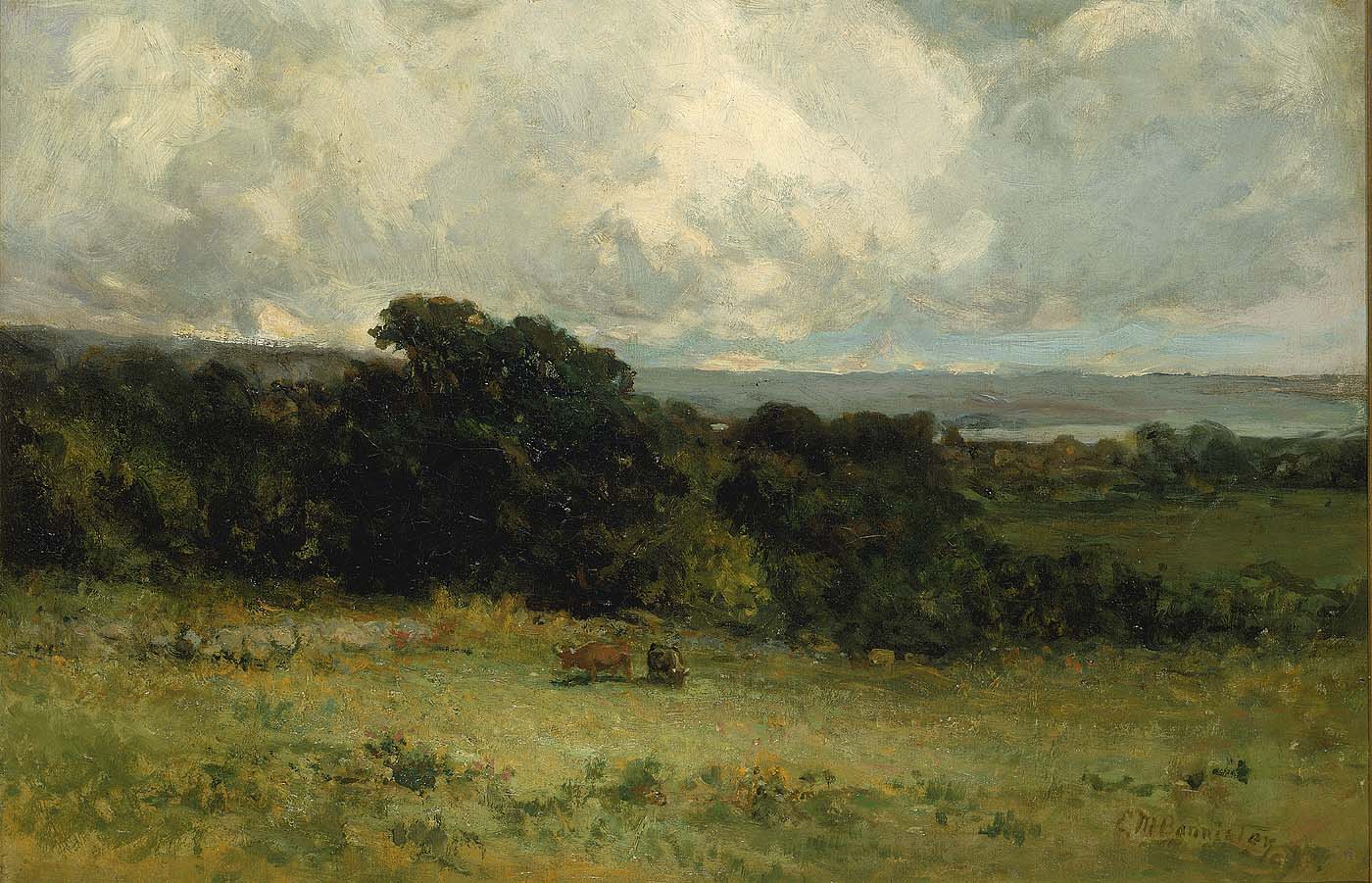

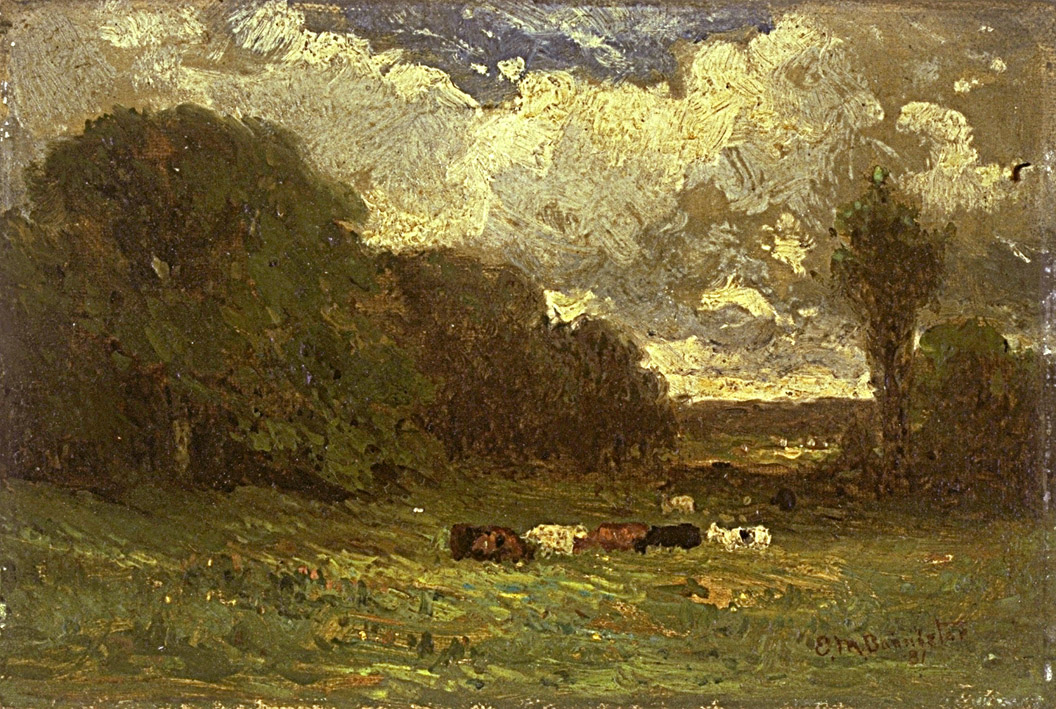

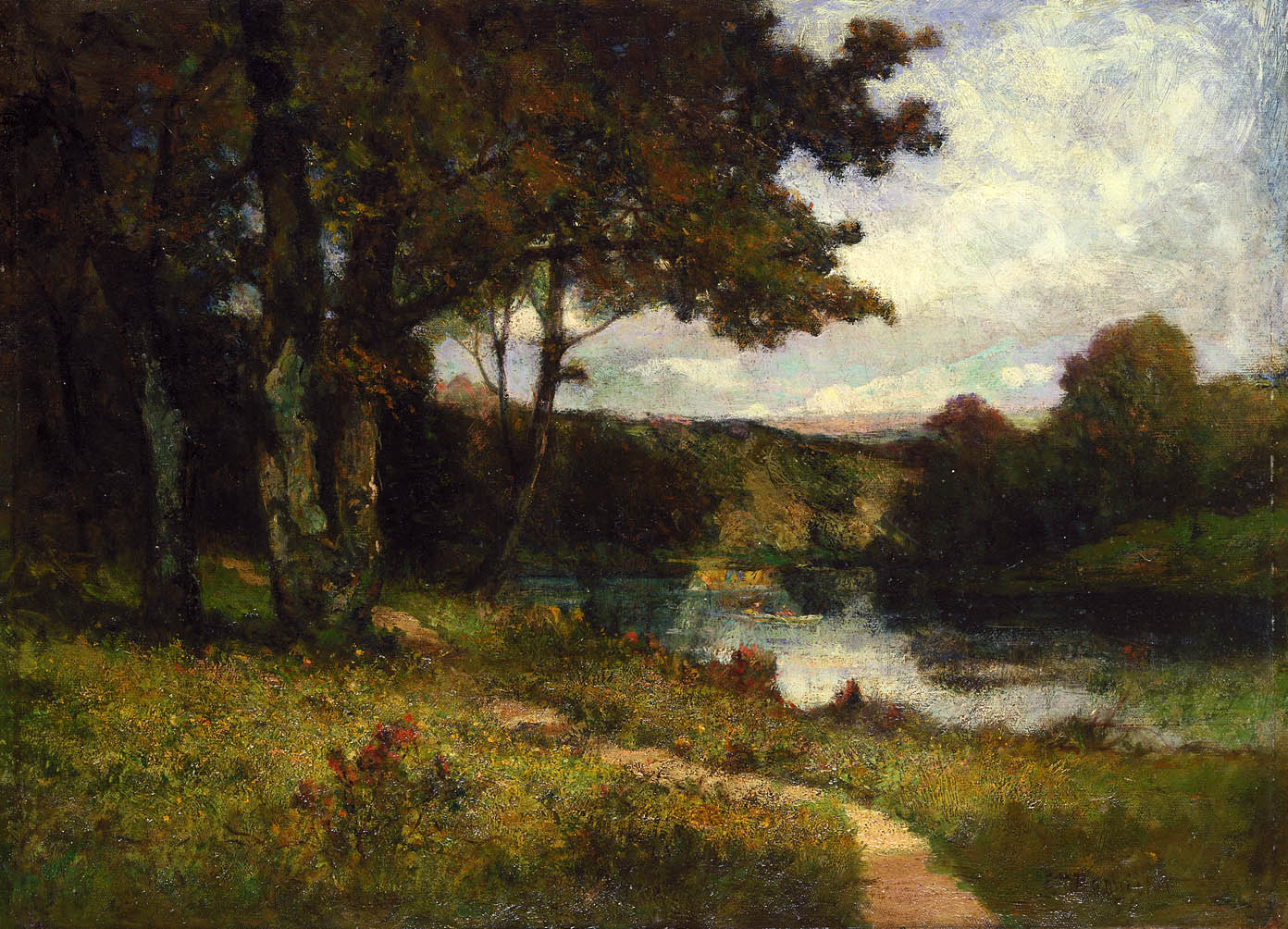

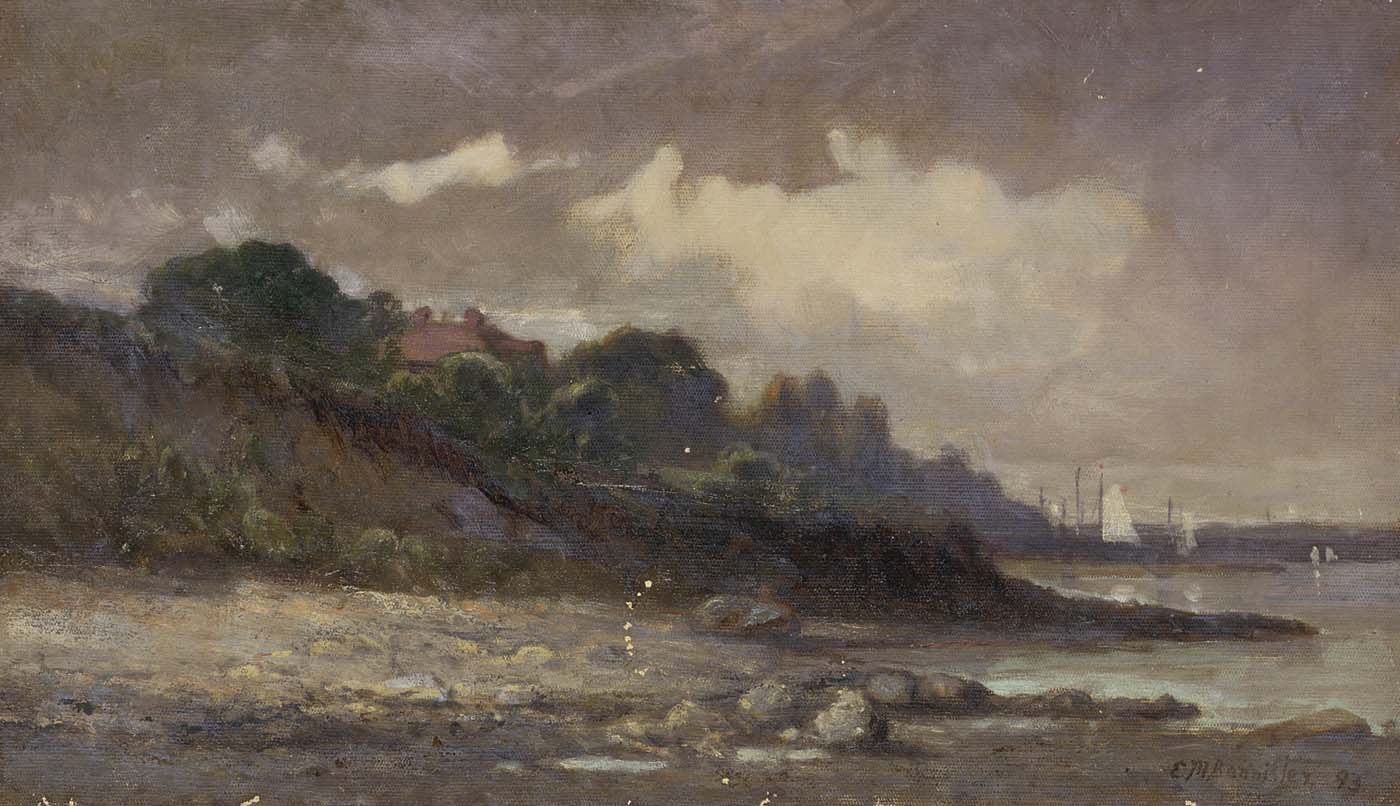

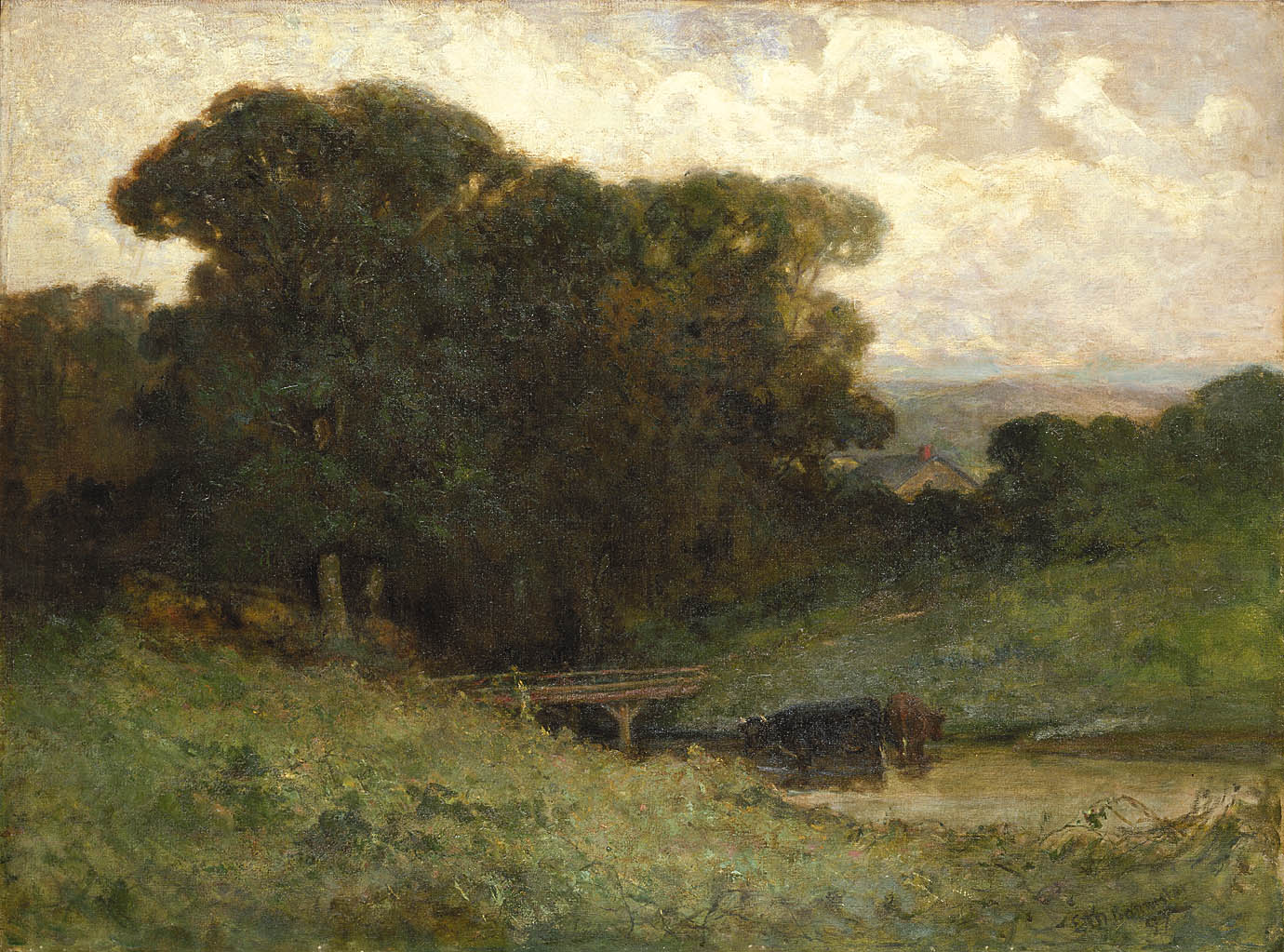

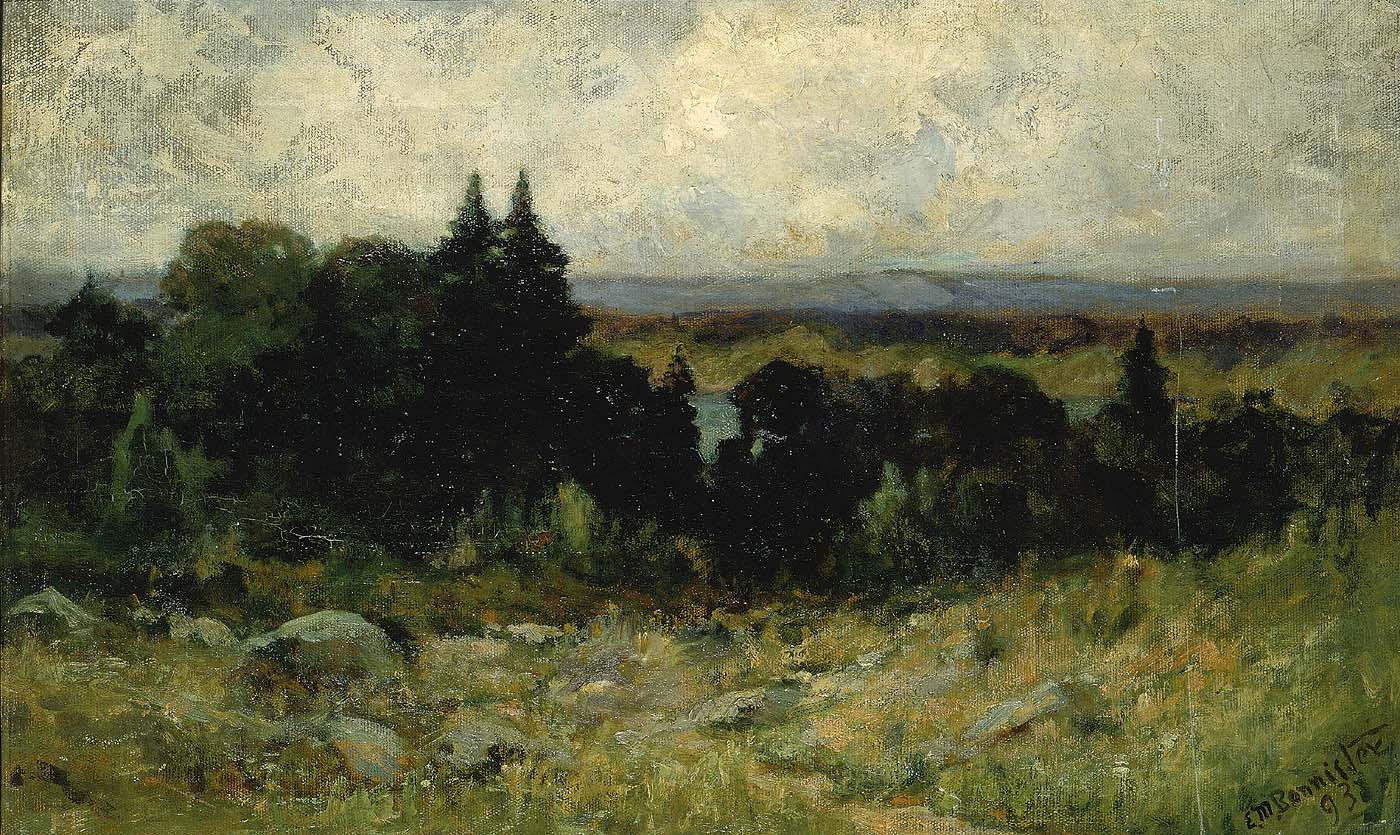

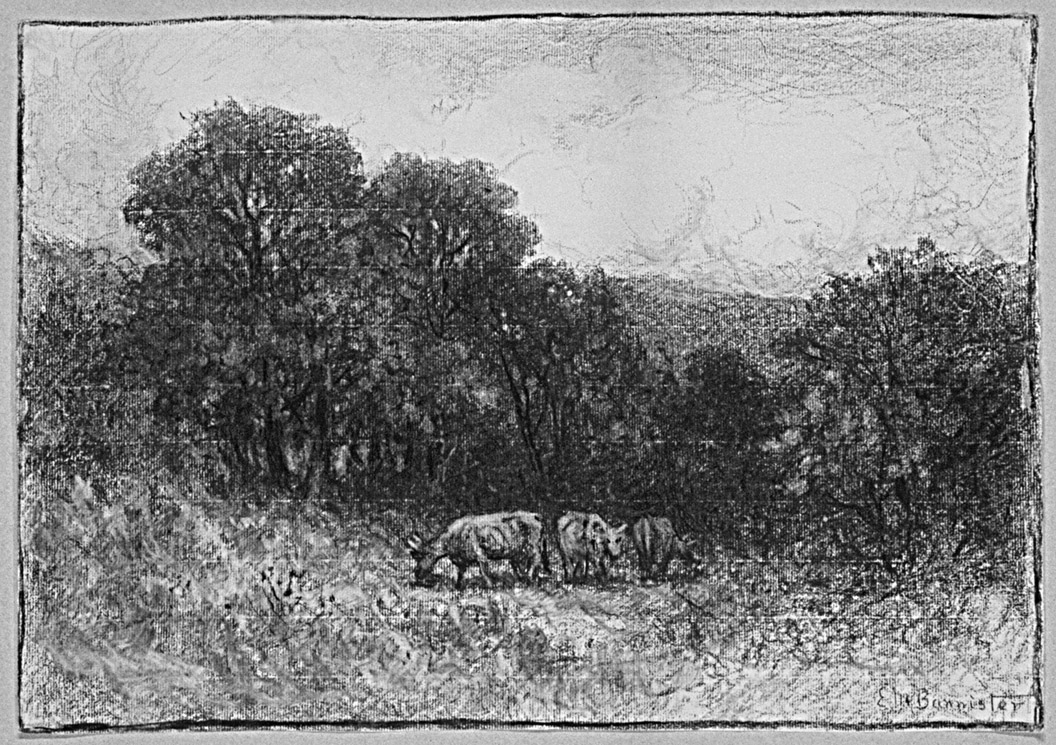

Following the Centennial Exposition, Bannister's reputation grew and numerous commissions enabled him to devote all his time to painting. He executed a large number of landscapes, most of which depict quiet, bucolic scenes rendered in somber tones and thick impasto. While Bannister'sinitial influence probably stemmed from the Barbizon-inspired works of William Morris Hunt, his paintings are reflective of an artist who loved the quiet beauties of nature and represented them in a realistic manner. Bannister's middle-period landscapes of the 1870s were generally executed in broad masses of heavy impasto with few details. They also evoke a tranquil mood that became one of the hallmarks of Bannister's style. Later landscapes of the 1880s and 1890s employed a more gentleimpasto and loosely applied broken color similar to impressionist techniques.

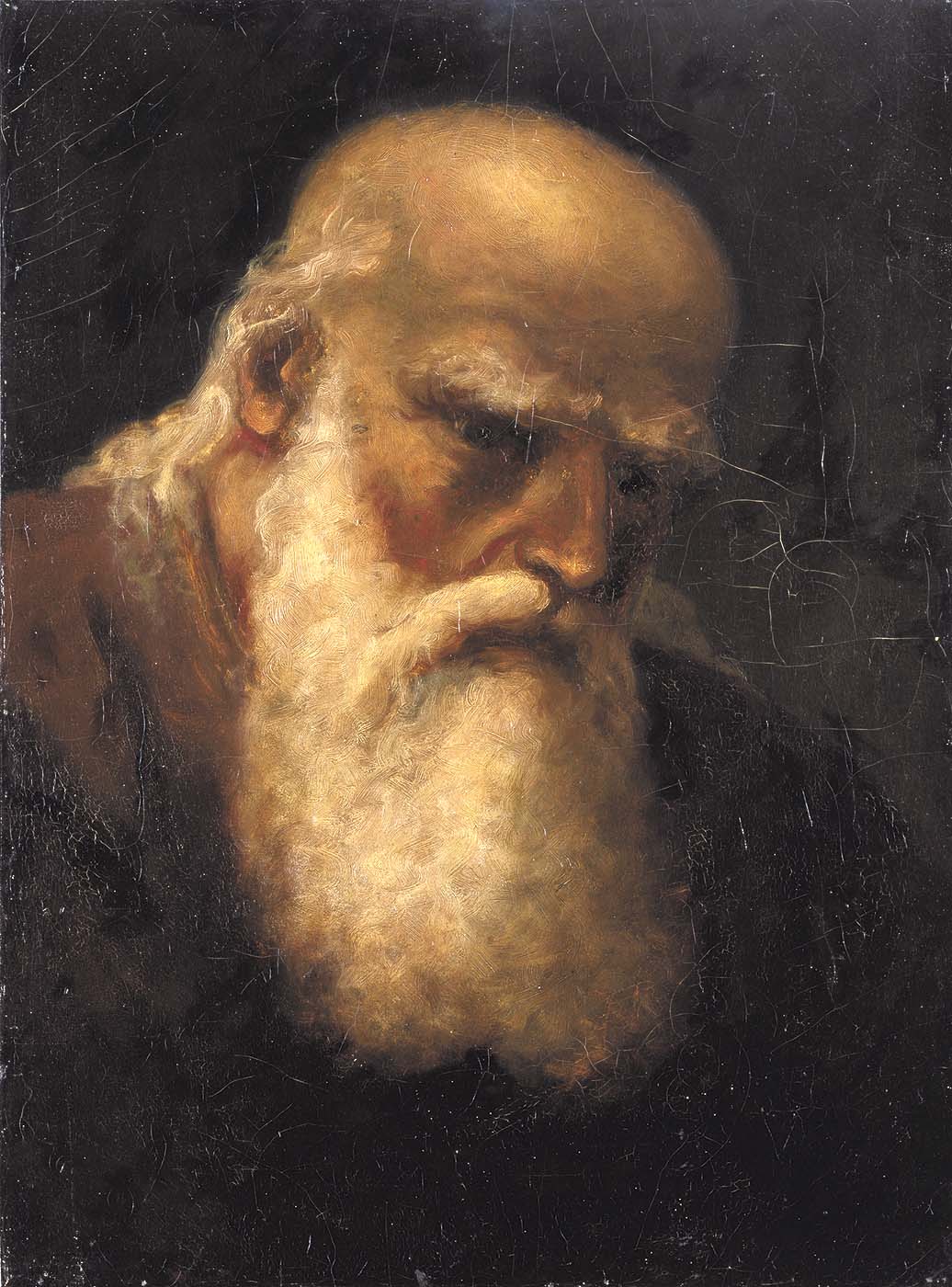

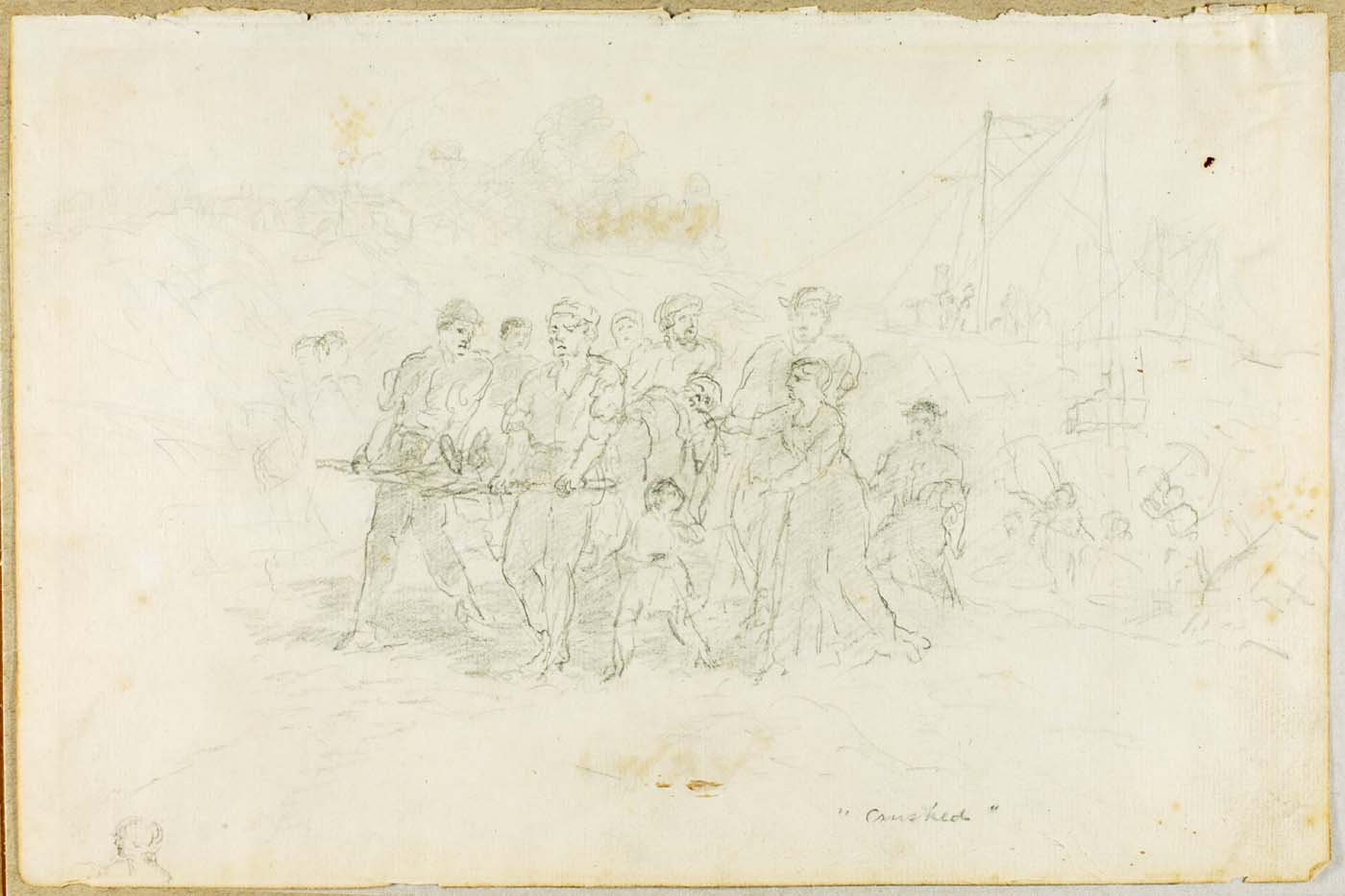

Many of Bannister's landscapes are small and have darkened considerably with age. His paintings contain no social or racial overtones, and the small figures seen frequently in his landscapes appear to be white. Although the majority of Bannister's paintings are landscapes, he also painted figure studies, religious scenes, seascapes, still lifes, and genre subjects. Bannister was attracted primarily to picturesque motifs including cottages, castles, cattle, dawns, sunsets, and small bodies of water, and he portrayed nature as a calm and submissive force in his works.

In spite of his limited training and experience, Bannister was among Providence's leading painters during the 1870s and 1880s. He was well liked and respected by his fellow citizens. On January 9, 1901, Bannister died while attending a prayer meeting at his church. Shortly after his death, the Providence Art Club mounted a memorial exhibition of 101 of Bannister's paintings owned by Providence collectors. Bannister's grave in North Burial Ground, Providence, is marked by a rough granite boulder ten feet high bearing a carving of a palette with the artist's name and a pipe. A bronze plaque also adorns the monument and is inscribed with a poem, which reads in part, "This pure and lofty soul . . . who, while he portrayed nature, walked with God." Edward M. Bannister was the only major African-American artist of the late nineteenth century who developed his talents without the benefit of European exposure.

Regenia A. Perry Free within Ourselves: African-American Artists in the Collection of the National Museum of American Art (Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art in Association with Pomegranate Art Books, 1992